A-levels: Brian Cox, China, and the recession

More than 40 per cent more students took maths A-level this year than five years ago, but modern languages and general studies are in decline. Channel 4 News looks at why.

Amid the “clearing scramble” for university places, there is another tale in yesterday’s A-level results: the remarkable growth of mathematics and Chinese.

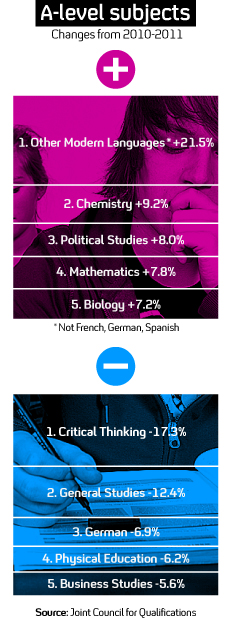

More students are also opting for science and technology A-levels, but other subjects are in decline, noticeably modern languages like French and German, as well as subjects considered by some to be “soft”, such as general studies and critical thinking.

The figures are startling: in the last five years there has been an increase of 40.2 per cent in the uptake of maths, while Chinese has had year on year growth of 30 per cent.

But in contrast, since last year the number of students taking critical thinking fell by 17.3 per cent, and German fell by 6.9 per cent.

The ‘Brian Cox’ effect

Are students listening to Universities Minister David Willetts, who said this week that “traditional” subjects should be valued more highly in the race for university places?

Possibly, but the so-called “Brian Cox effect”, coined by the managing director of the exam board Edexcel Ziggy Liaquat, should also not be underestimated.

Professor Cox, a particle physicist, hit the mainstream – after a stint in the band D:Ream – with TV series celebrating the joys of science, including his programme Wonders of the Universe.

There is the Brian Cox effect…he is an inspirational role model for aspiring scientists. Edexcel’s Ziggy Liaquat

Mr Liaquat told Channel 4 News: “The media does have an influence on the thinking of young people, and he is an inspirational role model for aspiring scientists.”

However, there is a wider context. A study done by the Institute of Education in 2009 looked into why students chose the subjects they chose between the ages of 14-19.

After GCSE-level, it found that the main reason young people gave for taking mathematics, science, physics or chemistry was “usefulness” – rather than other subjects which are perhaps viewed as less “useful”.

Mr Liaquat says the idea of “usefulness” has become even more important to today’s young people, who are bombarded with bad news about the economy and the job market.

“Two years ago, when these kids were making their choices, it was the start of the economic downturn,” he said.

“Businesses were crying out for more skilled people in science, English, maths. Students are savvy about their choices, what will bring them a successful outcome in terms of getting a job or getting to university.”

Rise of the dragon

The rise of China as a nation is a clear explanation for the rise of Chinese as a subject as well, Mr Liaquat explained. But students were not necessarily dropping other modern languages, like French, in order to take Chinese – as the figures may seem to suggest.

Language learning in the UK took a body blow in 2004, when the then Labour Government removed the rule that it was compulsory for schools in England to teach a foreign language to 14-16-year-olds. This probably explains the decline in language A-levels, but the fact that Chinese is rising despite this is a sign of the appetite for the language from students.

Mr Liaquat said: “Employers and students recognise that these qualities are portable, they don’t limit their future. They are seen as real value across many areas.”

But if students are so diligently matching what they study with what they think employers and universities want, why are bosses still regularly heard on the airwaves and in the press criticising either the lack of graduates or the skills that graduates come out of university with?

Earlier this week, entrepreneur Sir James Dyson, inventor of the eponymous vacuum cleaner, bemoaned the lack of engineers coming out of British universities and warned it could force British companies abroad.

Mr Liaquat admitted there was still a “challenge” out there on literacy and numeracy, but added: “There is a real response from students to the needs of business and higher education and for the UK economy that has got to be a good thing.”