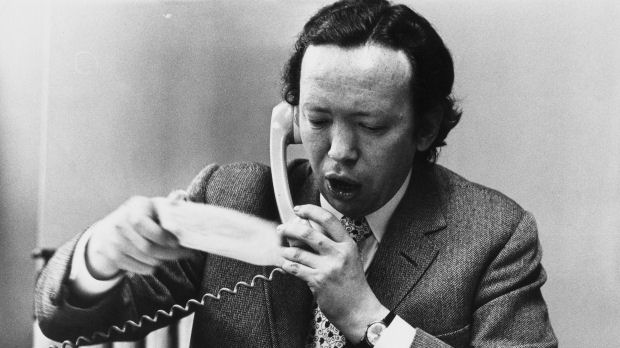

Anthony Howard: ‘A wonderful combination of paradoxes’

Political historian Anthony Howard died suddenly in December. His eulogy, by writer Robert Harris, describes a uniquely talented man who was a privilege to know.

Many writers have a voice in their head that cajoles or rebukes them as they work, and for almost a quarter century, that voice for me has been Tony Howard’s.

I was 29 when at his instigation I was hired as political correspondent by the Observer, even though I’d never written a newspaper article in my life. He taught me the trade.

Pictures courtesy of The Times

He took a paternal interest in me. Eventually I graduated to the Elysium Fields of what he called his “lost boys”. On Fridays and Saturdays I used to take my copy in to show him in his office, where he’d be sucking a wine gum or puffing on a cheap cigar.

Mostly he was kind, though he could be rude if necessary. He once described an article I’d written as “the work of a perfectly competent pork butcher”.

On another occasion he noted with pursed lips that I’d misspelt Iain Macleod: he called it “a vulgar error”.

Talking to Carol last week, she mentioned that Tony had been famous at school for his performances of Polonius and Lady Bracknell – and I’m not sure he ever entirely stopped playing either role. I can hear his voice now, as he stands at my shoulder, looking down at what I’ve written: “Call this a eulogy? You must be off your toot. You clearly haven’t done a hand’s turn. Even Trelford would have done a better job than this…”

Tony was a wonderful combination of paradoxes. In a characteristic inversion of the modern commonplace stance, he didn’t believe in God but he did believe in an organised religion.

He was almost literally born into it, on the 12th of February 1934, about 500 yards from where we’re sitting, in a church flat at 24 Cheniston Gardens. His father, Guy – “a poor parson,” in Tony’s words – was then a young priest here at St Mary Abbot’s and the infant Tony is reputed to have received from the parishioners of Kensington, some 300 items of baby wear – in which case it may be that the only time he was fashionably dressed was in his pram.

Tony continued to worship here until the end of his life – chiefly, he said “out of custom” and an “aesthetic appreciation of church services,” but also because he loved the Church of England. Jane Bonham-Carter recalls talking to Tony at a party last year, when he suddenly glanced past her and his face became suffused with pleasure. He had spotted that the Archbishop of Canterbury was coming over to speak to him.

He had his own strange language. The wireless was “the puff-puff radio”.

When his old friend and former brother-in-law, Alan Watkins, died last May, Tony organised his funeral. At the interment, there was a mix-up, the priest didn’t arrive, and Tony, rising to the challenge, found himself reciting over the grave, from memory, the funeral service from the Book of Common Prayer. I’m not sure which man, Alan or Tony, would have relished the many ironies of that scene more.

Tony followed the minutiae of ecclesiastical appointments as other men might study the football results. He could tell you the difference between a prebendary and a canon, just as he knew the order of precedence between a marchioness and a countess.

Here was another of his paradoxes: the left-wing journalist who looked and sounded like a member of the Establishment. He detested vulgarity. I don’t think I ever heard him swear. One of his greatest compliments was to observe: “that boy has beautiful manners.” His most damning insult was to call someone “a booby”, or, even worse, “a very low fellow”. He had his own strange language. The wireless was “the puff-puff radio”. Holidays were taken in “French France”. The Observer’s literary editor was always “Blakey Blake”. The News Editor, “Little Miss Muffett”. And so it went on.

His father was a lifelong Conservative and as a young schoolboy Tony had a picture of Winston Churchill on his wall. But quite early in his life, he decided, to quote the current phrase, that his “heart beat on the left”, and unlike others’, it stayed there. He was suspicious of wealth and privilege, despite – or perhaps because – he attended Westminster School and Christ Church. His family’s means were modest and he remained by nature frugal.

He recalled that at his first private school, in Highgate, the other pupils used to shout after him “charity bo”, even though he was sure his parents had saved to pay the full fees. He professed himself shocked by the way the son of John Strachey was bullied at Westminster, merely because his father was a minister in the Attlee government: that made him instinctively sympathetic to Labour. And at 15 he fell under the spell of Dick Crossman, who came to speak to the school political society in 1949. Forty years later Tony wrote in his biography of Crossman: “I can see him now – talking in that magnetic way that was entirely his own… I was not only beguiled, but bewitched.”

Tony was a member of the Labour Party for nearly sixty years: at one time he was the youngest Parliamentary candidate in the country, for Epsom, though he never fought the seat.

Tony, in typical English style, didn’t care much about political ideology. Ideology bored him almost as much policy – and policy bored him a very great deal.

He believed in a party that represented what the Bible calls “the hewers of wood and the drawers of water” – a favourite quote of his. He started out as a Bevanite, more or less, and – more or less – he remained one, long after Bevan had died, it being a characteristic of Tony’s that, having found something he liked – a political party, a dish in a restaurant, a suit, a friend – he saw no reason to change it, but stuck with it stubbornly, especially when it became unfashionable to do so.

He was never sectarian. Michael Heseltine was one of his oldest and closest friends, and was for a time his landlord and flatmate, in what developed into a legendary story of leaking roofs, skipped rent and live-in girlfriends that sounds like a cross between Rising Damp and The Odd Couple.

Tony, in typical English style, didn’t care much about political ideology. Ideology bored him almost as much policy – and policy bored him a very great deal. Crossman devoted fifteen years of his life to a Trollopian-sounding scheme called the National Superannuation Plan, yet Tony mentions it only twice in an almost 400-page biography. What interested him about politics, and about life in general, were the foibles of human character. That was what made him such a wonderful journalist. He would have been a terrible politician.

The last time I spoke to him, about a month ago, he ticked me off, in his usual Tonyish way, for having referred to journalism on Radio Four as “a profession”: it was, he rightly corrected me, “a trade” – a trade that he practised full-time from 1958 – first on Reynolds News and the Sunday Pictorial, then on the Manchester Guardian, the New Statesman, the Sunday Times, the Observer, the New Statesman again – this time as editor – the Listener – again, as editor – the Observer – again, this time as deputy editor – and finally at The Times, as obituaries editor.

Throughout these fifty-odd years he also worked constantly in broadcasting, presenting programmes on the BBC (both on television and puff-puff radio), on Channel Four, on ITV and on Sky. He was so closely involved in the annual journalism awards organised by What the Papers Say, that they became known as “the Tonys”.

It’s no secret that he would have liked to edit a national newspaper and he occasionally fancied himself a Machiavellian plotter to this end, but was, as Alan Watkins used to remark, endearingly hopeless at it. Seeking to mount a coup to become editor of the Observer in 1988, he waited, like some Latin American colonel, until Donald Trelford was out of the country, and then struck. Unfortunately, Donald turned out to be on Tiny Rowland’s yacht. The troops returned to their barracks. Tony left the paper.

He wrote three fine official biographies – of Dick Crossman, Rab Butler and Cardinal Basil Hume – and, with Dick West, one of the best journalistic accounts of British politics ever published, The Making of the Prime Minister (1964). If ever I wanted to tease Tony, all I had to do was tell him was that this was the book that made the youthful Peter Mandelson want to become a politician: it was a compliment he invariably received with a shudder.

As a journalist, he was a rare blend of talents. There may have been more knowledgeable political historians over the past 50 years. There may have been finer prose-stylists. There may have even been shrewder judges of public figures. But there was no one who combined all three abilities as successfully as Tony Howard.

To take just one article out of thousands: on December the 14th 1962, Tony wrote in the New Statesman about Tony Benn’s campaign to renounce his viscountcy. Presciently headlined (with a question mark) “Mr Home and Mr Hogg?” it pointed out that one unintended consequence of the Peerage Bill then going through Parliament would be to widen the field of potential successors to Harold Macmillan, for if a Labour lord could renounce his title so too could a Tory. No one else had then spotted it. The-then Earl Home, many years later, told his official biographer that reading Tony’s article was the moment he realised he could become prime minister, and he started making plans accordingly.

Given that Tony once told me that every day Home was prime minister he woke up ashamed to be British, he can’t have been especially pleased by this achievement. But it did show just how remarkable a political commentator he was.

There is a coda to this story. In 1993, Tony embarked on a six-year Indian summer as obituaries editor of The Times – his ideal job in many ways: “rowing people across the Styx,” as he called it – and I remember the schoolboyish glee with which he described how he now had access to all those Establishment obituaries that were held on file, and how he could subtly alter them, usually by the simple insertion of a sentence beginning, “However, comma”. Alec Douglas-Home was one recipient of this treatment; Princess Margaret another.

One of the reasons Tony loved those years editing obituaries – what he called “the hinge of history and journalism” – was that they took him back into an office again. And that brings me to the last thing I want to say. He hated working alone, which perhaps explains why he wrote only four books. He needed the company of other people: for stimulus, for diversion, for gossip.

We will at least always carry in our heads that wonderfully rich, wise and distinctive voice.

In particular – a final paradox for a man who sometimes seemed set in his ways – he adored the company of young people. “If there’s one thing I can’t bear,” he used to say, “it’s an old sweat.” He’d been helped at the start of his career by Alastair Hetherington and John Freeman and it delighted him to be in a position to perform the same service for another generation: he called it quite simply “the most important part of being an editor”.

Journalism is ephemeral. What once seemed brilliant issues and memorable articles are now as dead as poor old Crossman’s National Superannuation Scheme. But the people Tony brought on – that remarkable collection of young writers at the New Statesman, and the many others he encouraged afterwards at the BBC, the Listener, the Observer, and The Times – these people really are his true professional monument.

It was a privilege to have known him, and to have known, through him, Carol, his wife of forty-five years. He would not have achieved half what he did without her. It is a measure of his devotion to her that she even persuaded him to spend some time in the country, at Ludlow – although I must say that whenever he visited us in the country he never removed his black Oxfords, or forgot his navy blue raincoat.

“I hope I’m not frightened of death,” Tony said in an interview two years ago. “I’m frightened of illness and pain and that kind of thing. But if I could just heel over, would I mind all that much? I don’t know. I tend to believe that death is the end, but I’m not sort of 99 per cent convinced that is true. I could be wrong about that, and I might get an agreeable surprise.”

Let us hope that he is indeed experiencing that “agreeable surprise”. As for the rest of us – no longer boys, alas – we will at least always carry in our heads that wonderfully rich, wise and distinctive voice, which is, even now, telling me to cut the guff, and kindly leave the pulpit.