Chisora v Haye brawl just the latest boxing feud

The uproar surrounding the brawl between Dereck Chisora and David Haye has led to some critics calling for them to face life bans. But boxing feuds have gone on for over than a century.

Chisora’s threat to shoot and burn his Bermondsey nemesis looks tame compared to some of boxing history’s most acrimonious grudges.

Everybody remembers Mike Tyson telling Lennox Lewis, “I want your heart, I want to eat your children,” having actually taken a bite out of Evander Holyfield’s ear several years earlier.

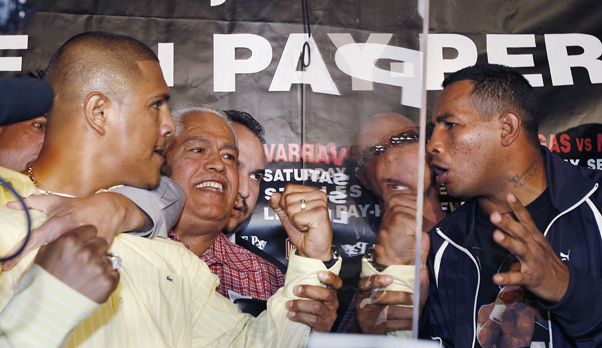

Ricardo Mayorga vs Fernando Vargas (pictured above)

Like Tyson before him, Mayorga has a long history of provoking pre-bout brawls.

The Nicaraguan incensed Cory Spinks before their fight in 2003 by pledging to reunite him with his recently deceased mother. His 2007 opponent, Fernando Vargas, found that comments about his wife crossed the line.

The pair had a spectacular brawl during their pre-match press conference, after Mayorga told him: “I will do Vargas a favour by retiring him in this fight so his family doesn’t have to suffer every time he steps in the ring.

“I’m going to do your wife a favour and not let her cry any more after I disfigure you.”

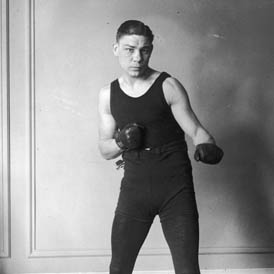

Mickey Walker vs. Harry Greb

Mickey Walker and Harry Greb’s bout and subsequent melee outside the ring in July 1925 is now the stuff of boxing mythology. Greb, a middleweight, beat Walker, the welterwight in 15 enthralling rounds. A scrap for the ages, the pair decided to hit the town together.

In 1933, Walker recounted their long night together to the Spartanburg Herald-Journal (read the original article here).

“In [to the club]walked Greb (pictured) as soon as I was settled and he had a girl with him.

“He insisted that I join his party. We must have danced for hours. In fact, we danced so long, Harry’s girl disappeared.

“Finally, it was getting light and we stumbled out into the morning air. All of a sudden, Harry grabbed me by my neck. ‘Just to show you I can lick you anytime anywhere. I’m going to give you another walloping right now.'”

A passing policeman broke up the scuffle and threatened to beat them with his club.

“Hey, I’m Mickey Walker and that’s Harry Greb. We’re just kidding a little. Don’t hit us,” Walker implored the policeman. “[He must have been the only] person in New York who hadn’t heard about the fight.”

The pair managed to evade the policeman’s capture, but as soon as Walker got home, his phone rang. “Mickey,” said Greb “I’m sorry for what I just did, but don’t forget I can always lick you.”

In the interview, Walker added: “Harry Greb, there was a man.”

Larry Holmes vs. Trevor Berbick

Following his first round knockout of Tim Anderson in Miami in 1991, Larry Holmes was giving a press conference, when Berbick, whom he had beaten 10 years earlier, asked him for a rematch. Berbick refused, saying: “I do not like him or respect him.”

The conference ended, but Holmes and Berbick – both of whom had previously beaten Muhammad Ali and would later lose to Mike Tyson – brawled in front of the Diplomat Hotel. Police officers broke up the fight.

Berbick began explaining what had happened to the waiting press, but Holmes clambered on top of a car and drop kicked his rival. They never fought inside the ring again.

Riddick Bowe vs. Jorge Gonzalez

The glass-breaking incident at Chisora’s post-match press conference is not unprecedented.

In 1995, it was hard to keep Riddick Bowe and Jorge Gonzalez from each other’s throats. The two had become the bitterest of enemies when Gonzalez, representing Cuba, beat American Bowe at the Pan American games some years earlier. Such was their mutual antagonism that during a press conference leading up to their bout, Gonzalez hurled a plate at Bowe and threw ice from a glass into his face.

“He’s just a knucklehead,” said Bowe. “He wants to be a gangster like Castro, but he’s really a bully who can’t fight.”

At their next press conference, organisers put up a plastic barrier to separate them, but it was not enough to stop the pair going for each other again.

Jack Johnson vs. Jim Jeffries

Jack “The Galveston Giant” Johnson, regarded by many as the best heavyweight of all time, had one of the most famous rivalries of all time with James Jeffries, at the turn of the last century.

But much of their enmity was something of a cold war, because the latter refused to fight a black boxer.

By the time they eventually squared up in 1910, Johnson had travelled the world and cleaned up the division, calling out Jefferies at every turn.

It was only when Johnson became the first ever black heavyweight champion after demolishing Tommy Burns in Australia two years previous that the then long-retired Jeffries answered calls to fight him. By that time, Johnson had been chasing him for 14 years. And Jeffries was under enormous pressure to restore the world champion belt to a white man’s waist.

“Jim Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the golden smile from Jack Johnson’s face,” the writer Jack London wrote at the time.

And Jeffries played along. “I feel obligated to the sporting public at least to make an effort to reclaim the heavyweight championship for the white race… I should step into the ring again and demonstrate that a white man is king of them all,” he said leading up to the bout.

Such was the vitriol directed towards Johnson before the fight that the New York Times wrote: “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbours.”

Johnson humiliated his nemesis over 15 rounds in Reno, Nevada, refusing to knock him out in order to prologue his shame.

“(Jeffries) was saved from this crowning shame only by his friends pleading with Johnson not to hit the fallen man again. At the end of the fifteenth round, Tex Rickard raised the Black arm, and the great crowd filed out, glum and silent. The reviled Johnson was like a Black panther, beautiful in his alertness and defensive tactics,” the Associated Press wrote after the fight had ended.

Following the victory, race riots swept the country, with several black people shot and stabbed while celebrating Johnson’s triumph. In all, 19 people were killed in connection with the fight, 251 were seriously injured and there were 5,000 cases of disorderly conduct.

The New York Times wrote: “Most of the casualties were Negroes who were hunted down by white mobs, mostly because of boasts by the Blacks that they had finally demonstrated their superiority over the whites.”