Can we beat climate change with geoengineering?

Some of them sound like the stuff of science fiction, but can ideas from the brave new world of geoengineering slow or reverse global warming?

Geoengineering – trying to change the environment in a bid to counter climate change – is the big buzzword in green circles following the publication of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) pessimistic new report.

The panel of scientists says the earth is undoubtedly getting warmer, with ice sheets and glaciers are shrinking and the permafrost thawing out in the northern hemisphere. And the experts say they are now 95 per cent certain that most global warming since the 1950s is man-made.

There is no consensus about what, if anything, we can do to mitigate the effects of climate change. But for the first time, the IPCC has given prominent space to a discussion of geoengineering.

It comes after Russia made a controversial proposal to add support for more research into geoengineering techniques like iron fertilisation and sulphate aerosol sprays into the IPCC’s recommendations.

With little hope of the kind of drastic cuts in carbon emissions that environmentalists say will be necessary to significantly alter the momentum of climate change, it appears that some governments are warming to the idea of geoengineering.

What kind of ideas are on the table, and what are their chances of success?

Carbon dioxide removal focuses on trying to capture and store the gas blamed for most man-made global warming. Suggested techniques include:

Dumping iron

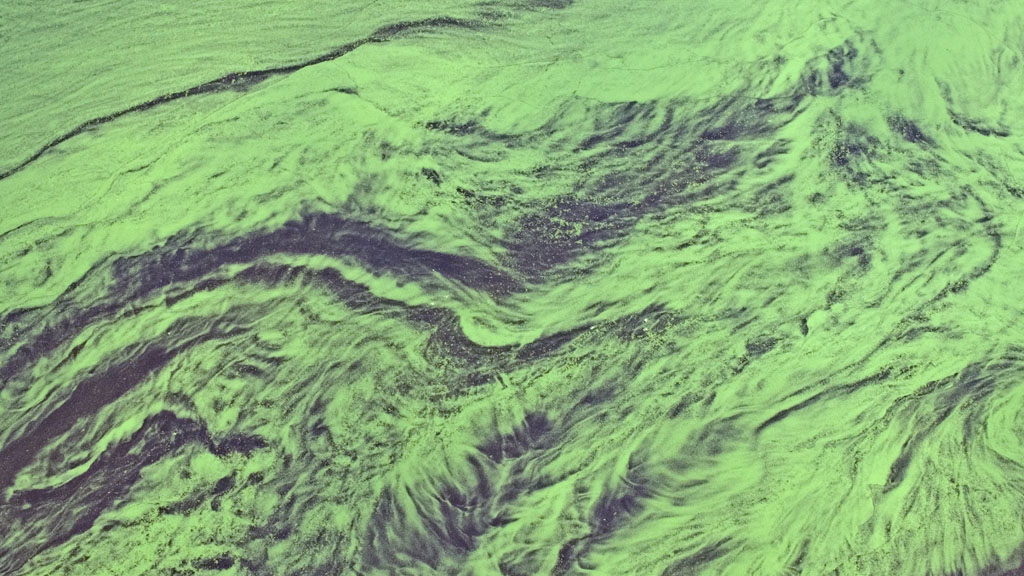

The theory is simple: we drop huge amounts of iron dust into the oceans, where it acts as a nutrient for algae. As the marine plant life blooms, it absorbs CO2 from the air, which gets stored on the bottom of the ocean when the algae dies and sinks.

But the science is unproven, with some sceptics suggesting that the carbon may not really get locked away for long enough to make a difference.

Several test runs have been carried out, with uncertain results. Most controversially, the US businessman and environmentalist Russ George helped a group of indigenous Canadian Haida people dump 100 tons of the metal into the Pacific.

Canadian officials stepped in, claiming it was an act of illegal dumping. The organisers of the experiment claimed it was an “amazing success” but scientists say it is impossible to verify the results.

Experts at the UN have said that plans to fertilise the ocean should be contemplated with the “utmost caution”, given the risk of upsetting the delicate balance of life under the sea, adding: “We cannot afford to gamble with the ocean.”

Greening the Sahara

Zimbabwean biologist Allan Savory’s TED Talks lecture on reversing desertification in the Sahara is one of the most popular in the site’s history.

Unusually, Mr Savory thinks that massive herds of grazing livestock could help return CO2 to “pre-industrial” levels.

The theory is that herds of cattle and goats have helped create deserts by stripping the land of grass and releasing methane.

But we can turn the clock back using “holistic land management” – grouping the animals together tightly and rotating the herd around different patches of grass while the rest recovers.

The technique means farmers no longer have to burn dead grassland, which releases huge amounts of carbon, and have apparently managed to turn swathes of desert land green again, helping to take the gas out of the air and trap it in the soil.

Despite some apparently impressive photographic evidence of deserts turning into lush grassland, scientific evidence of the benefits of rotational grazing is mixed.

Other proposed techniques come under the banner of Solar Radiation Management – reflecting sunlight to cool the planet slightly.

Man-made volcano

We know that major volcanic eruptions like Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991 can have a cooling effect, because massive clouds of sulphurous dust shooting up into the stratosphere reflect sunlight back into space, so less radiation reaches the earth.

Some heavyweight scientists have proposed trying to mimic the effect of volcanoes by using planes to release droplets of sulphuric acid at high altitude.

But there are number of potential hazards, including the risk of destroying more of the ozone layer in the process, and the danger of triggering drought.

Wrapping the ice caps

Plastic wraps are already dragged across glaciers in the Alps to protect them from the sun’s rays and stop the ice from melting.

Geoengineers have tried using similar reflective blankets in Greenland, but the cost of covering enough land to make the technique effective on a global scale may be prohibitive.

Storms of criticism

Despite increasing interest from entrepreneurs, billionaires and governments including the US, China, Germany, Britain and Russia, geoengineering has been heavily criticised by some scientists and environmentalists.

Today’s IPCC report preaches caution about how much impact carbon dioxide removal would really have on CO2 levels.

Reflecting sunlight could be effective in reducing global temperatures, the panel thinks, but would do nothing to combat problems like the seas become more acidic.

Both methods “carry side effects and long-term consequences on a global scale”, the IPCC concludes.

Critics have pointed to the lack of hard results, warned of the unintended consequences of tampering with ecosystems, and have called geoengineering a distraction for governments from the real work of reducing carbon emissions.

Parliament’s science and technology committee has called for the UN to regulate major geoengineering projects before countries start taking matters into their own hands and carrying out experiments that could affect the entire planet.