Copenhagen: no view from the summit?

After months of hype the Copenhagen climate change summit took place in December 2009 but resulted not in a binding deal between the world’s leaders, but an “accord”.

The challenge facing nearly 200 countries was to agree a deal which would see carbon emissions brought under control and global temperature increases kept in check.

Many said that was a minimum requirement. The Danish hosts said it was “an opportunity the world cannot afford to miss”.

The meeting of 15,000 delegates was tasked with overcoming deep distrust between rich and poor nations about sharing the cost of emissions cuts.

In the end no binding deal was signed and after a “rollercoaster” of all-night deal making many of the smaller nations complained the accord left them threatened by rising sea levels.

They said the deal cut by the US with India, Brazil, China and South Africa and effectively imposed on everyone else failed to give the tough commitments that were needed to tackle disastrous climate change.

From the Earth Summit to Copenhagen

Julian Rush followed the long road from the Brazil Earth Summit in 1992 the climate change summit in Copenhagen.

In 1992 world leaders came to Brazil's holiday playground pledging action on the newly identified threat of climate change. Here was the world taking the environment seriously for the very first time.

It was fresh from agreeing a deal on banning the chemicals that caused the hole in the ozone layer and hopes were high that dealing with climate change would be just as easy.

But the same cracks existed then as they did 18 years later.

Speaking in 1992, Pakistan's then environment minister Anwar Saifullah Khan said: "We cannot save the environment if the rich refuse to provide greater aid to the poor."

It is people like the 40,000 residents of the Colombo favela in Sao Paolo who are already suffering most from climate change.

In the pre-summit "I will if you will" stand-off, President Lula was first off the mark with an offer to restrain Brazil's emissions as the country grows. He offered to enforce drastic cuts in deforestation in the Amazon, rather than measures that might affect Brazil's growth.

Dr Jose Marengo, from Brazil's Earth System Science Centre, told Channel 4 News: "For the Amazon region, what is now a tropical rainforest may become, according to some of our climate experiments, more like a savannah type vegetation."

Developing countries like Brazil were furious there was no legally binding deal, and there is still a mountain to climb.

‘Costs and benefits’ in tackling climate change

In a special edition of Channel 4 News, then Climate Change Secretary Ed Miliband spoke to Jon Snow and a public panel about the costs and potential benefits of climate change in shaping green industries of the future.

How much has the government told us about the cost to every household in Britain and the personal sacrifices we will all have to make if Britain is to become a low carbon economy?

In a discussion with members of the public at Channel 4 News, Ed Miliband said: “We’ve said that as a result of making a transition of our energy system to lower carbon it will be a cost of something like 8 per cent additionally on bills by about 2020.

“So there are costs to making the transition. It will mean big changes in our energy, big changes in relation to our homes, because we’ll need more insulation in our homes, we’ll need to change the way we get energy in our homes, and it will mean changes to the transport system as well.

“I think the important point to say is that there are costs, but there are benefits as well. Because if Britain can be part of a Copenhagen agreement we can see jobs flow into this country in the new green industries, we can see more energy security because if we have low carbon energy like windpower it is likely to be homegrown energy.

“And I think we can improve people’s quality of life. So there are definitely costs, and I’m very open about that. I think there are benefits as well. Quite apart from the most important benefit which is avoiding the environmental disaster that would result if we don’t tackle climate change.”

Can we save the world's lungs?

Deforestation accounts for one fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions and halting it would be as powerful as closing all the world's coal-fired power plants.

Details of the Redd (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation) plan are complex but at root it involves rich countries paying countries with rainforests not to cut down trees.

Jonathan Miller travelled 2,000 miles across the Amazon Basin, which contains more than half the world's remaining rainforest, to ask Brazilians who live and work there what they make of this plan.

Read more

Climate change: last decade ‘warmest ever’

More than 6 months after Copenhagen, scientists in 48 countries concluded that the past 10 years were the warmest on record.

A Met Office climate expert told Channel 4 News Science Correspondent Tom Clarke the decade on decade trend is “stonkingly obvious”.

The “State of the Climate” report issued annually by the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), also suggests that despite a freezing winter for many, 2010 will be the warmest year ever recorded. The report also collates, for the first time, parallel data sets on global warming trends from independent scientists that contradict criticisms raised by the “climategate” emails leaked at the University of East Anglia.

Click here to see: NOAA report

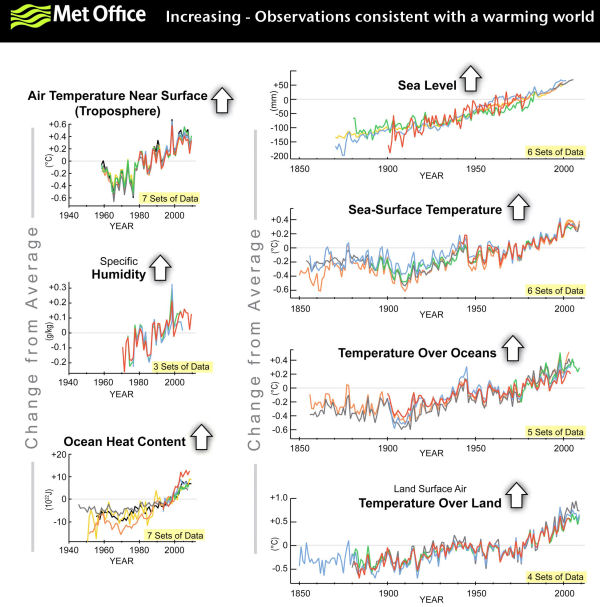

In this year’s report scientists at the Met Office Hadley Centre in Exeter copiled global data sets for 10 major indicators all linked to a warming climate. Analyses of things like sea temperature, snow and glacier melting, global humidity and the extent of arctic sea ice all point to a warming planet.

“When we follow decade-to-decade trends using different data sets and independent analyses from around the world, we see clear and unmistakeable signs of a warming world,” says Peter Stott, Head of Climate Monitoring and Attribution at the Met Office.

A key criticism emerging from the leaked emails was that there were flaws in how scientists at UEA had compiled their data set of global land surface temperature.

The new comparisons by Stott and his team show that the UEA data sets is in almost complete agreement with two others produced by independent teams of researchers in the US For other global warming trends – for example global sea surface temperature – they compared seven different global data sets. All of them suggest that the world’s oceans are getting slightly warmer.

Stott acknowledged that from year-to-year there can be big variations in things like sea-ice cover or global air temperatures that cannot be ascribed to global warming, but that the trend over the longer-term was clear. “If you look at variability from year-to-year it’s a bit of a moot point,” says Stott, “but if from decade to decade [the warming trend] is stonkingly obvious.

“Decade to decade [the warming trend] is stonkingly obvious.” Peter Stott, Met Office

There are some measurements that appear to contradict evidence of a warming planet. The amount of sea ice around the Antarctic continent has remained about the same in recent years, despite annual losses of around 10 per cent from the Arctic ocean. However a closer look at wind patterns and the cooling effect of the ozone hole over the South Pole explain the sea ice phenomenon says Stott.

Click here to see Tom Clarke studying ocean acidity in the Arctic

And not all of the measurements agree. The two existing data sets for land surface temperature held by US scientists suggest that 2010 is already the warmest on record. However, the controversial “HADCRUTEM3” data from the University of East Anglia indicates it is merely the second hottest year after the current record holder 2005.

The clear trends contained in the ten data sets presented today are “unequivocal,” he says. “The evidence just continues to stack up and gets ever stronger.”