Did Theresa May blow it?

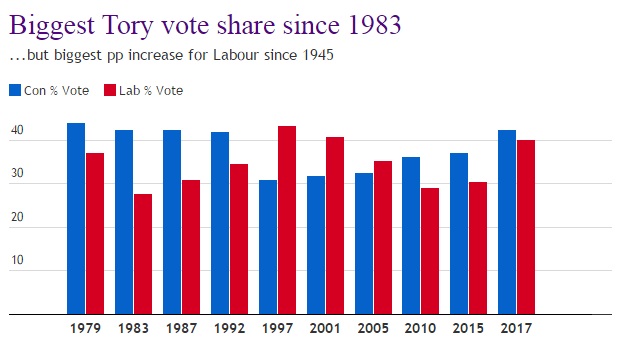

The Tories actually increased their share of the vote to its highest since Margaret Thatcher’s famous post-Falklands victory of 1983.

But at the same time, Labour’s share of the vote increased dramatically too. It went up by almost 10 percentage points – the biggest jump between general elections since 1945.

So people voted Tory and Labour?

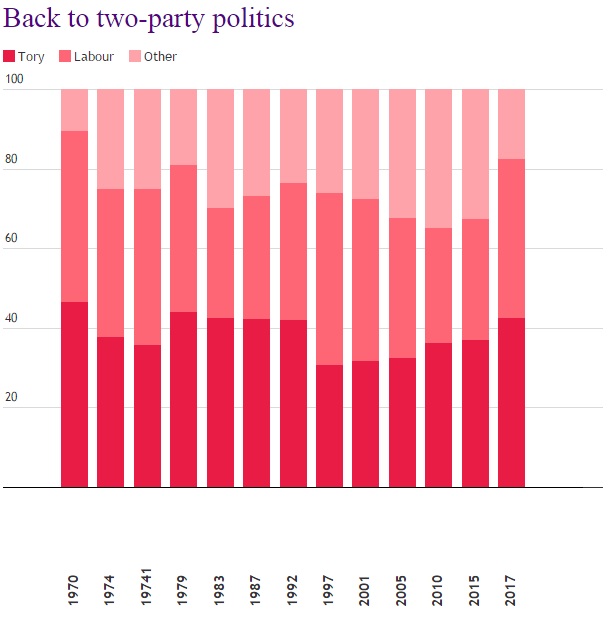

That’s basically the story. The two biggest parties increased their share of the vote, and smaller parties were generally squeezed out.

In fact, more than 80 per cent of voters backed either Labour or the Tories – the biggest proportion since 1970:

It remains to be seen whether this marks the return to the two-party system that dominated postwar British politics, or whether large numbers of people voted tactically this time, as some polling suggested might happen.

Was this election all about Brexit?

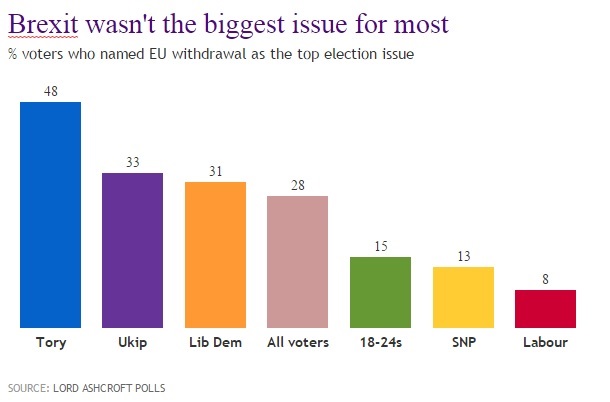

Post-vote analysis suggests that most voters did not in fact single out Brexit as the most important issue for them as they decided which way to vote.

Lord Ashcroft Polls have published the most detailed research we have seen so far into why people voted.

It suggests that Britain’s withdrawal from the EU was most important to Tory voters, with 48 per cent naming it as the most important issue.

This fell away to 15 per cent among 18-24-year-olds and just 8 per cent among Labour voters:

Obviously, this doesn’t support the idea that the election result was all about a Brexit protest vote from young Labour voters.

Sky Data said only 14 per cent of voters said Britain’s relationship with the EU was the most important issue deciding how they voted, making it less important than health, the economy and immigration.

Did young people make the difference?

Lots of people were tweeting about a 72 per cent turnout among 18-24-year-olds this morning, but we can’t find a source for this.

Sky News have been quoted as a source by other news outlets as putting 18-24 turnout at 66.4 per cent, up from 43 per cent in 2015. But again, we don’t know where this comes from originally.

An exit poll for the NME showed a big increase in voter turnout among the young. Some 53 per cent of 18-24-year-olds voted, compared to 41 per cent in 2015.

That exit poll also backs the Lord Ashcroft data in suggesting that two-thirds of 18-24-year-olds voted Labour.

That’s not a surprise: a lot of previous surveys show a marked preference for Labour among the youngest voters. But that should already have been “priced in” to the polls.

The most likely scenario is that there was a much larger-than-expected turnout among a demographic already inclined to vote Labour, but we await better research on youth turnout.

How did the pollsters do?

Most did not predict a hung parliament, but one or two high-profile companies did.

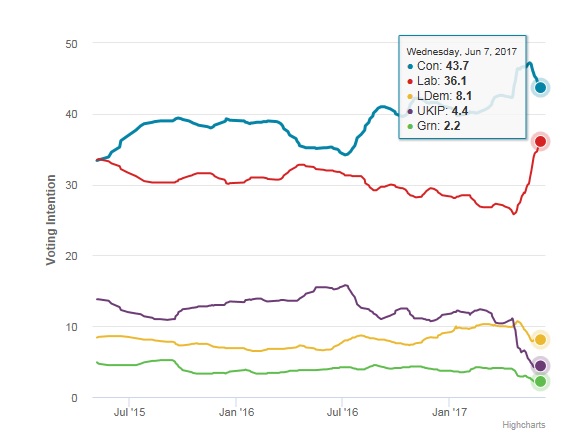

Britain Elects publishes this handy poll of polls, which takes a rolling average of major voter intention polls:

It’s clear that these surveys are better at predicting some things than others. The share of Tory support in the final poll of polls is quite close to the actual vote share – 43.7 instead of 42.4 per cent.

The support for the Lib Dems and Greens are close to the real voting patterns too – within a couple of percentage points.

The polls also captured the late surge in support for Labour and the collapse of the Ukip vote. But it seriously underestimated the eventual Labour vote. If the polls have a problem, it’s with Labour.

This could really be a problem with younger voters, who as we have seen are much more likely to back Labour.

We had a look at this last week, and it seems that pollsters tended to adjust their methodology after 2015, when young voters failed to turn out in the expected numbers to vote for Ed Miliband.

Polling companies seemed to think this would be a chronic problem, likely to be repeated in later general elections, rather than a symptom of disillusionment with politics in the last election.

In fact, it looks like the lesson here is that young people can be motivated to vote in large numbers when politicians make the right offer to them.

Do we need to change our voting system?

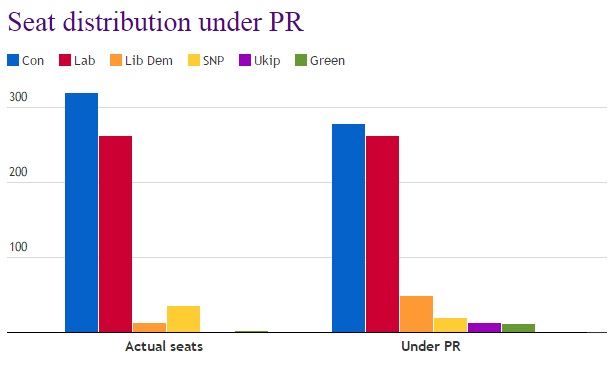

The argument will run and run, but here’s how many seats would have been allocated to the biggest parties if today’s results are fed through the D’Hondt system of proportional representation:

The Conservative lead shrinks even more, the smaller parties get a much bigger voice in parliament, and we avoid some of the more disproportionate outcomes of First Past the Post.

Today Ukip failed to win a seat, despite getting more than half a million votes. Their support was spread out too thinly geographically to win any seats.

The Greens got fewer votes overall but held on to their Brighton stronghold.

Northern Ireland’s SDLP lost all three seats, despite getting much the same share of the vote as in the last election.

And the Lib Dems, despite failing to pick up the votes of large numbers of disgruntled Remainers, don’t have too much to complain about: their vote share fell but they picked up four seats!

Update: we updated some of the figures in this piece to reflect the final results. A confusing reference to the SNP’s vote share was removed.