Across the country, university students are submitting final pieces of coursework to complete their degrees.

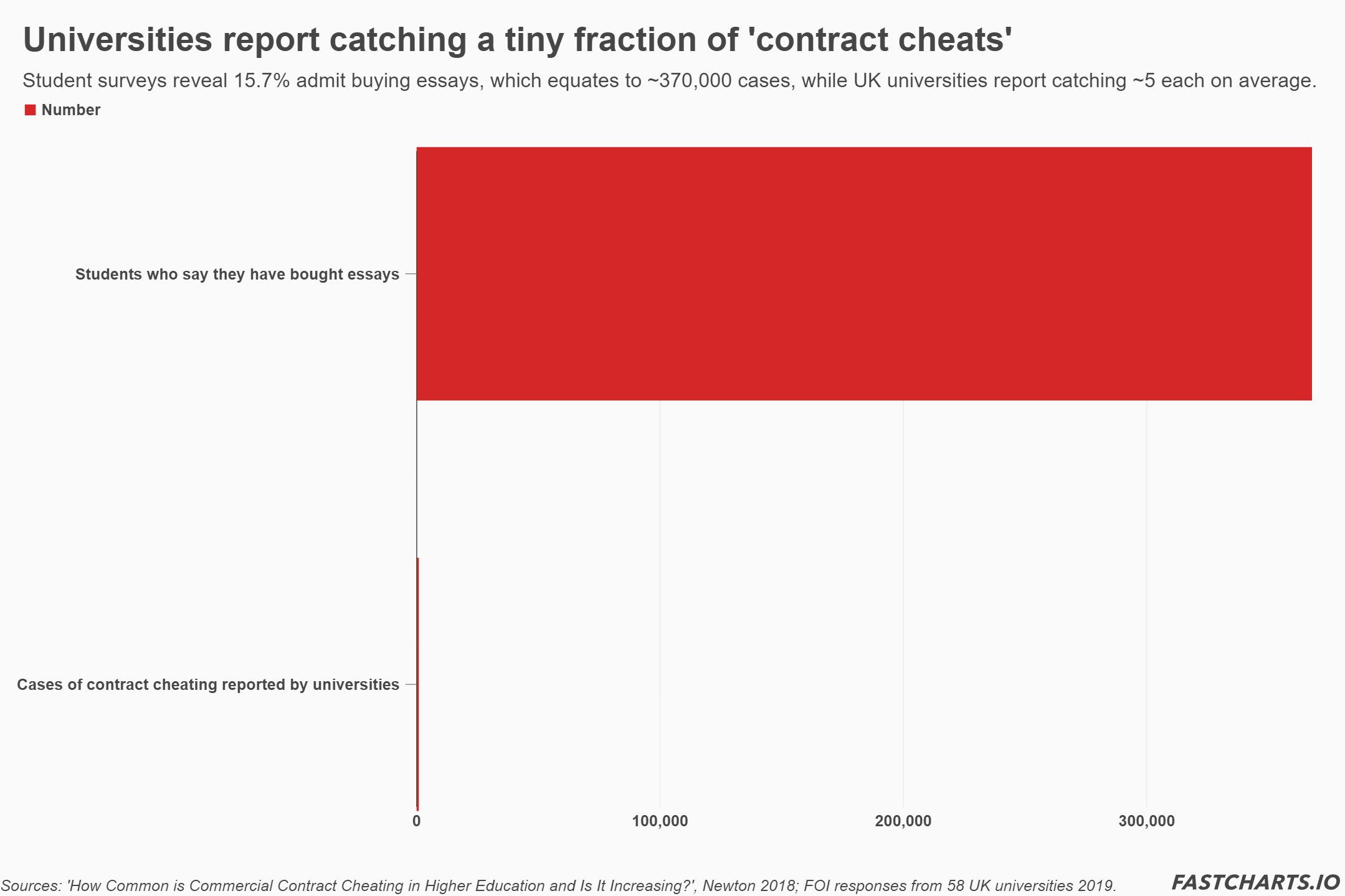

While the majority are acting in good faith, student surveys find that one in six privately admit to buying in essays — suggesting hundreds of thousands engage in so-called “contract cheating” each year.

But it seems universities have failed to comprehend the sheer scale of the problem.

FactCheck can exclusively reveal that about half the universities that responded to our freedom of information request were unable to put a figure on how many contract cheating cases they’d found last year.

And the 58 institutions that could provide stats only reported catching around 300 contract cheats between them. Most were students from outside the EU.

How many contract cheats were caught last year?

Nearly every university in the UK uses some form of anti-plagiarism software, which scans electronic versions of a student’s work to see if they have dishonestly copied from online sources or other publications.

“Contract cheating” is when students buy or commission others, often companies known as “essay mills”, to write bespoke essays or coursework for them because this original work won’t be flagged by such software.

Only 58 out of the 99 universities that responded to our query were able to tell us how many contract cheats they’d caught last year. A further 66 institutions didn’t respond at all.

Some gave an exact number, others quoted a range of figures (e.g. “fewer than five”) to avoid identifying individuals. Taking these ranges into account, the 58 institutions reported a combined total of between 278 and 316 cases of contract cheating in 2017-18. That’s an average of five or six cases per institution.

The University of Bedfordshire has the dubious honour of topping this list, finding 59 cases of “work produced by a third party” last year. As well as “bought in” essays, they told us this could also include cases where friends or family had provided so much help with an assignment that it was no longer the student’s own work.

A spokesperson for the University told FactCheck: “At Bedfordshire we put a lot of work into stamping out student submission of work produced by a third party. We regularly raise the awareness of academic staff so they are alert to the potential for cheating, and we are transparent and rigorous in our response to it.

“To keep the matter in perspective, in 2017-18 there were only 59 cases identified at the University, a hugely small percentage of the total number of essays submitted that year.”

The University of Westminster came in second place (28 cases), followed by Oxford Brookes and Sheffield Hallam (24 each), Sussex (23) and Middlesex (20).

What does this tell us about these institutions? It could be that they are hotbeds for contract cheating. But all the evidence we have suggests this is unlikely.

As we’ll see later, one in six students in the UK confess to contract cheating — which is why it’s so striking to hear from some universities that they don’t hold records of any such cases.

And as we’ve already discovered, the majority of universities either didn’t reply to our request for information, or couldn’t provide us with any figures on the number of contract cheating cases they’ve detected.

The most plausible explanation for Bedfordshire, Westminster, et.al. coming top of this list is that these institutions are simply better at spotting this type of behaviour, and/or better at centralising their records of it, than other UK universities.

Bedfordshire told us that they “carry out an early assessment of students to assess their writing style and ability” so that if suspicions are raised later, they are better placed to gauge if a piece of work is the student’s own.

One university, Brunel, told us “it is very difficult to determine if a student has ‘bought in’ coursework unless they admit it.” Asked about the number of cases, they said “no students have admitted ‘buying in’ coursework during the period of interest.”

Some universities said that contract cheating is recorded in individual departments’ files, rather than in a university-wide database. So it’s possible they are catching more cases of contract cheating than their central records show.

But unless institutions document and centralise records on this phenomenon, we are forced to rely on imperfect snapshots.

Most contract cheating cases in our sample involve international students

International students — those from overseas who are not EU nationals — were involved in 58 to 73 per cent of contract cheating cases reported by universities in our sample.

To put those findings in context, non-EU international students make up about 14 per cent of all students at UK universities.

The tip of the iceberg?

There’s no way of knowing for certain exactly how many people are buying in essays to complete their university degrees.

In 2018, Professor Phil Newton of Swansea University, reviewed 71 student surveys on the topic of cheating, going back to 1978.

The studies he looked at from 2014 onwards found that on average, one in every six students (15.7 per cent) say they have bought or commissioned work from a third party.

If that’s accurate, it suggests about 370,000 of the UK’s 2.3 million students have engaged in contract cheating at some point in their studies. Across our 165 universities, that would work out at an average of 2,200 cases per institution.

Compare that to the figures universities reported to us: in our sample, the average university detected between five and six cases of contract cheating last year. Extrapolating across all higher education institutions, we can (very roughly) estimate that UK universities caught a combined 915 contract cheats in 2017-18.

Some said they hadn’t recorded any such cases at all. And the University of St Andrew’s went further: it’s not that they don’t have records of a case, they told us they “can confirm there have been no instances of contract cheating this academic year”.

There are limits to the cheating surveys. Professor Newton points out that people who agree to take part in surveys “are more likely to be older, female, well-educated and from a higher socioeconomic background” – characteristics he says are “in complete contrast to the factors associated with an increased likelihood of engaging in cheating”.

He also notes that in some studies, there was no guarantee of anonymity for the students taking part.

All of this suggests that the already-high levels of contract cheating reported in such surveys could even understate the true extent of the problem.

What are universities doing about it?

We asked each university to tell us whether they have “policies in place to identify students who are ‘buying in’ bespoke essays, assignments and other coursework from outside”.

Of the 98 institutions that answered our request, 47 per cent could not point to a rule explicitly forbidding the practice (we verified this by checking university rulebooks for phrases like “purchased essays”, “essay mills” and “ghosting”).

However, many of those without a specific policy told us that cases of this kind would be covered by their existing rules on academic misconduct.

One university told us that they use guidelines from the higher education watchdog, the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA), to spot and investigate possible contract cheating.

The QAA says “one of the most effective ways of detecting cheating is familiarity with a student’s normal output (their writing style and standard of work, for example).” When examiners suspect an essay has been bought in, the QAA also suggests carrying out a “viva assessment”, where students are interviewed in person to establish whether they authored the work themselves.

Responding to our query about how they identify contract cheating, seven institutions — Aston, Aberdeen, Liverpool Hope, the London Business School, the Open University, the University of Bristol, and the University of Chichester — told us that they use software services like Turnitin to detect plagiarism.

But that doesn’t quite answer our question.

The version of Turnitin that is currently used by 98 per cent of UK universities can tell whether an essay or sections of it have been lifted from online sources or other published work. It cannot detect whether an assignment has been bought in. This is the very reason students approach so-called “essay mills” in the first place.

So we were surprised when one institution, Canterbury Christ Church University, went further, telling us: “the University uses the software Turnitin to identify potential cases of bought essays.”

We thought perhaps they were referring to a new Turnitin programme launched in March 2019, “Authorship Investigate”, which is designed to help manage contract cheating cases. The software uses “forensic linguistic analysis” to see if a given piece of work is consistent with the student’s previous writing.

But the university told us that although they “have had discussions with Turnitin and intend to use their new ‘Authorship Investigate’ tool”, they had not yet deployed the software.

And even if they had, Turnitin told FactCheck that Authorship Investigate is not a way of flagging up potential cases of contract cheating where there is no prior suspicion of foul play — it’s a tool that can provide evidence to help investigators work out whether someone who is already suspected of buying in an essay has done so.

The onus remains on universities, and academics and examiners, to raise suspicions in the first place.