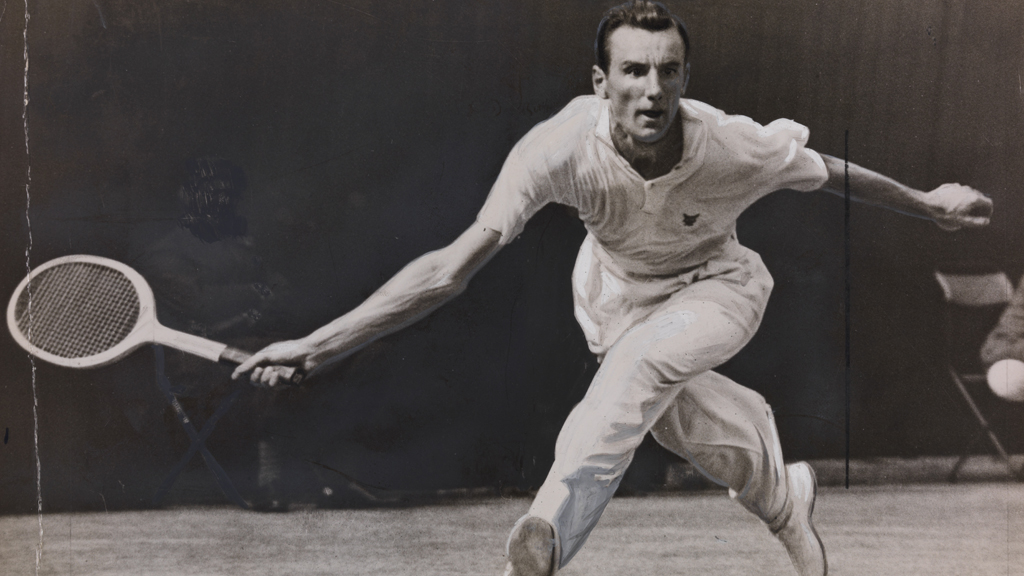

Fred Perry: tennis champion, class warrior

As Andy Murray becomes the first British man to win a tennis grand slam since Fred Perry 76 years ago, Channel 4 News looks back at the career of the champion generations tried and failed to emulate.

He dated Dietrich, launched a clothing label favoured by generations of music fans, and helped to invent the sweatband. But it was Frederick John Perry’s career as an amateur tennis player that cast a shadow over generations of male British tennis players, including Roger Taylor, Tim Henman and the Lloyd brothers. Until now.

Andy Murray’s US Open victory against Novak Djokovic means that Fred Perry’s legacy of eight grand slam singles and five doubles titles will sit a little easier on the shoulders of the Scotsman and those British players who follow him.

Northern background

But Perry himself did not have it easy, either. While British tennis stars featured more prominently in men’s tennis in the 1930s than today, the players Britain produced were normally from upper or middle class backgrounds.

By contrast, Perry was the son of Samuel, a cotton spinner from Stockport, whose involvement in local politics took the family around the north west of England.

The Perrys eventually settled in Ealing, west London, when Samuel Perry became national secretary of the Co-operative Party. It was there that young Fred learned his tennis skills on a court next to their housing estate.

Between 1934 and 1936 Perry won Wimbledon three times in succession, attracting the adoration of the crowds, particularly as he contrasted sharply with the privileged background of most of those associated with the All England Club at that time.

Off the tennis court, Perry kept the gossip columns busy. He had a relationship with Marlene Dietrich, was engaged to the British actress Mary Lawson, and in 1935 married an American film star Helen Vinson.

His decision to turn professional in 1937 led him to be virtually ostracised by the tennis establishment and he relocated to America, becoming a US citizen in the late 1930s. During the Second World War, he served his adopted country in the air force.

Trend spotter

After the war he showed a knack for trend-spotting, collaborating with an Austrian footballer to create a wrist-worn sweatband before launching a line of tennis shirts which became a hit with mods, skinheads and other musical tribes.

While he made an unprecedented contribution to British tennis, he only began to achieve recognition in his homeland in his later years with a statue of him unveiled at Wimbledon in 1984. After his death in 1995, he received further recognition with a walking route and a council building named after him in Stockport.

But his influence on tennis in the country of his birth has not been immediately apparent, with no British success in the men’s singles at Wimbledon or any of the other three grand slams for 76 years.

In fact, some commentators believe that Perry may have even unwittingly had a negative influence on the British game, with his biographer Jack Kramer claiming he was a physical freak and that people could not be taught the hit a forehand shot the way he did. Those who were taught to play that way were “ruined”, Kramer added.