Gaddafi – from pariah to ally and back again

Muammar Muhammad al-Gaddafi seized power in Libya in 1969 and ruled until 2011, bringing to its people relative prosperity but subjecting them to a hardline, oppressive dictatorship.

During his 42 years in power, Gaddafi has been described as a despot, a financier to international terrorists and a volatile eccentric, as well as a revolutionary hero and strategic partner to the West.

He manufactured a cult of personality in which he depicted himself as almost deity-like and imposed this mythology on virtually every Libyan in the form of his infamous Green book.

Gaddafi’s eccentricities have provoked ridicule and fear, and in recent years he has taken his brand of anti-Imperialist rhetoric to the highest altar, with hours-long, conspiracy-fuelled diatribes before the United Nations.

But it is the ruthless repression of his own people that will be remembered by many Libyans who had long cast envious eyes across the Mediterranean to Europe.

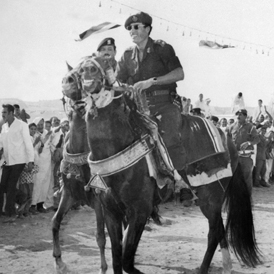

Photo gallery: The rise and fall of Gaddafi

Humble beginnings

At the start of his career, Gaddafi was feted by his countryfolk as an emancipator, a radical and progressive political thinker and, above all, a bringer of wealth to a previously impoverished north African former colony.

Gaddafi was born to peasant Bedouin herdsmen in 1942 in a tent near the coastal town of Sirte.

During his teens, Gaddafi became transfixed with the rise to power of Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser and took on many of his early anti-Imperialist and Arab nationalist ideologies.

He was an ardent believer in unifying all Arab states into a single Arab nation and later tried without success to merge Libya, Egypt and Syria into a federation. A similar attempt to join Libya and Tunisia ended in acrimony.

Gaddafi followed a military career that included spells abroad in Greek and British Army schools. In 1963, he attended the Benghazi Military Academy from where he and a few fellow militants devised a plot overthrow the pro-Western Libyan monarchy, led by King Idris I.

And six years later, at the age of just 27, Gaddafi and his fellow conspirators staged a bloodless and unopposed coup in Tripoli while King Idris I was out of the country on a visit to Turkey.

Eliminating all opposition, Gaddafi assumed power, named the country the Libyan Arab Republic, and immediately set about seizing total control of the country’s oil industry.

He famously told foreign oil executives: “People who have lived without oil for 5,000 years can live without it again for a few years in order to attain their legitimate rights.”

In 1977 he changed the country’s name to the Great Socialist Popular Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah (State of the Masses) and allowed people to air their views at people’s congresses.

Read more: Muammar Gaddafi 'dies of wounds'

Infamy

But while his early political manoeuvres closely mirrored those of his idol Nasser and pointed to potentially democratic foundations, Gaddafi soon whipped Libya in a different direction: one which led to autocracy and isolationism.

Fuelled by his anti-imperialist ideologies, he funded and supported militants and terrorists around the world and assassinated Libyan exiles.

It was in 1986, when Libya was blamed for the bombing of a Berlin nightclub frequented by American soldiers, in which two soldiers and one civilian were killed, that Gaddafi first became an international pariah.

In retaliation, US President Ronald Reagan sent warplanes towards Tripoli and Benghazi, with their mission to kill the “mad dog of the Middle East”, a nickname that would endure.

Instead, the planes kiled Gaddafi’s adopted daughter.

Libya was also accused of supplying the explosive substance Semtex to the IRA, which used it to carry out bombings in the 1980s.

Among attacks carried out by the IRA with the imported plastic explosive were the Harrods bombing of 1983, which killed six amid Christmas shopping crowds, and the Enniskillen atrocity of 1987 that left 11 dead during a Remembrance Day service.

In 1992 UN sanctions were imposed to pressure Tripoli to hand over two Libyan suspects for trial for the 1988 Lockerbie airliner bombing over Scotland, crippling oil-rich Libya’s economy.

Return to the fold

Gaddafi, shunned internationally for much of his rule because the West accused him of terrorism, abandoned his programme of prohibited weapons in 2003 to return Libya into international mainstream politics.

In September 2004, US President George W. Bush formally ended a US trade embargo as a result of Gaddafi’s scrapping of the arms programme and taking responsibility for Lockerbie.

Oil and infrastructure deals were struck with several countries, including Britain, and Gaddafi was considered to be “on side”.

Al Megrahi release

Relations with the west became strained again when, despite pleas from the White House and relatives of the victims of the Lockerbie bombing, the only man ever found guilty in relation to the attack was set free in 2009.

Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed Al Megrahi, who is terminally ill with cancer, was released on compassionate grounds and flown back to his family in Libya as he was deemed to have only months to live.

The decision of the Scottish Justice Secretary to release al Megrahi provoked a furious response in Scotland and beyond – the fury compounded by the fact that Al Megrahi is still alive in 2011.

The demise

When the first calls for a Libyan “day of rage” were circulated – inspired by the arab spring uprisings in the region, Gaddafi pledged to protest with the people, in keeping with his myth of being the “brother leader of the revolution” who had long ago relinquished power to the people.

As it turned out, the scent of freedom and the draw of possibly toppling the colonel, just as Egypt’s Mubarak and Tunisia’s Ben Ali had been toppled, was too strong to resist among parts of the Libyan population, especially in the east.

Nato launched its bombing campaign in March after the United Nations Security Council authorised the use of all necessary means to protect civilians. Pro-Gaddafi forces were closing in on the city of Benghazi, where Gaddafi had vowed what he termed the “traitors” would be hunted down like rats.

Photo gallery Gaddafi: the writing on the wall - post-revolutionary Libyan graffiti

Maintaining his defiant stance, Gaddafi described the rebels are armed criminals and al-Qaeda militants and called the subsequent Nato operation an act of colonial aggression aimed at stealing Libyan oil.