Gastric bandwagon: the key questions on obesity

The NHS advisory body Nice is recommending we lower the bar for stomach surgery. How fat do you need to be to get a gastric band these days? And will it save the country money?

How fat are we?

The NHS relies on body mass index (BMI) as the main measure of obesity. BMI is calculated by dividing your weight by your height squared. The NHS calculator is herefor anyone who wants to check their score.

A BMI number of 25 to 30 means you are overweight. Over 30 is obese and over 40 is variously described as “morbid” obesity or “Obesity III”.

Between 1993 and 2012, the proportion of adults that were obese rose from 13.2 per cent to 24.4 per cent among men and from 16.4 per cent to 25.1 per cent in women.

The proportion of adults with a normal body mass index fell in the same period from 41.0 per cent to 32.1 per cent in men and from 49.5 per cent to 40.6 per cent in women.

The figures for children are slightly less depressing, with obesity rates falling slightly in recent years.

What if I’m a bodybuilder?

The guidance recognises that people with a lot of muscle mass rather than fat can end up having a high BMI score.

Nice recommends that doctors “interpret BMI with caution in highly muscular adults as it may be a less accurate measure of adiposity in this group”.

Bodybuilder Anita Albrecht hit the headlines earlier this year when a nurse told her she was overweight, according to BMI, and recommended a low-calorie diet, without taking Ms Albrecht’s athletic physique into consideration.

Because of the limitations of BMI, Nice suggests that clinicians think about using a second measure, waist circumference, to assess obesity.

The latest figures show that proportion of adults with a raised waist circumference went up from 20 per cent to 34 per cent among men and from 26 per cent to 45 per cent among women between 1993 and 2012.

In men, a waist measurement of less than 94cm (37in) is low, 94 to 102cm (40in) is high and more than 102cm is very high. For women, less than 80cm (31.5in) is low, 80 to 88 cm (34.5in) is high and more than 88cm is very high.

How bad could things get?

Being overweight increases the risk factor type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart attacks and many other health problems.

An obese woman is almost 13 times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than a woman with a healthy weight. For men, the risk factor is just over five.

Academics have attempted to count the cost to society of treating all this avoidable illness.

Nice says people being overweight and obese cost the economy almost £16bn in 2007 (more than 1 per cent of GDP). That cost could rise to around £50bn in 2050 if obesity rates continue to rise.

Modelling published in the Lancet predicted 11 million more obese adults in the UK by 2030, with the bill for the NHS rising by up to £2bn a year.

Not everyone agrees that obesity will continue to become more prevalent. There is some evidence of obesity rates levelling off in developed countries, while the developing world is rapidly catching us up.

What are the new recommendations?

Current guidelines say only people with a BMI of 40 or above, or 35 and over with a serious condition like type 2 diabetes, should be considered for bariatric surgery.

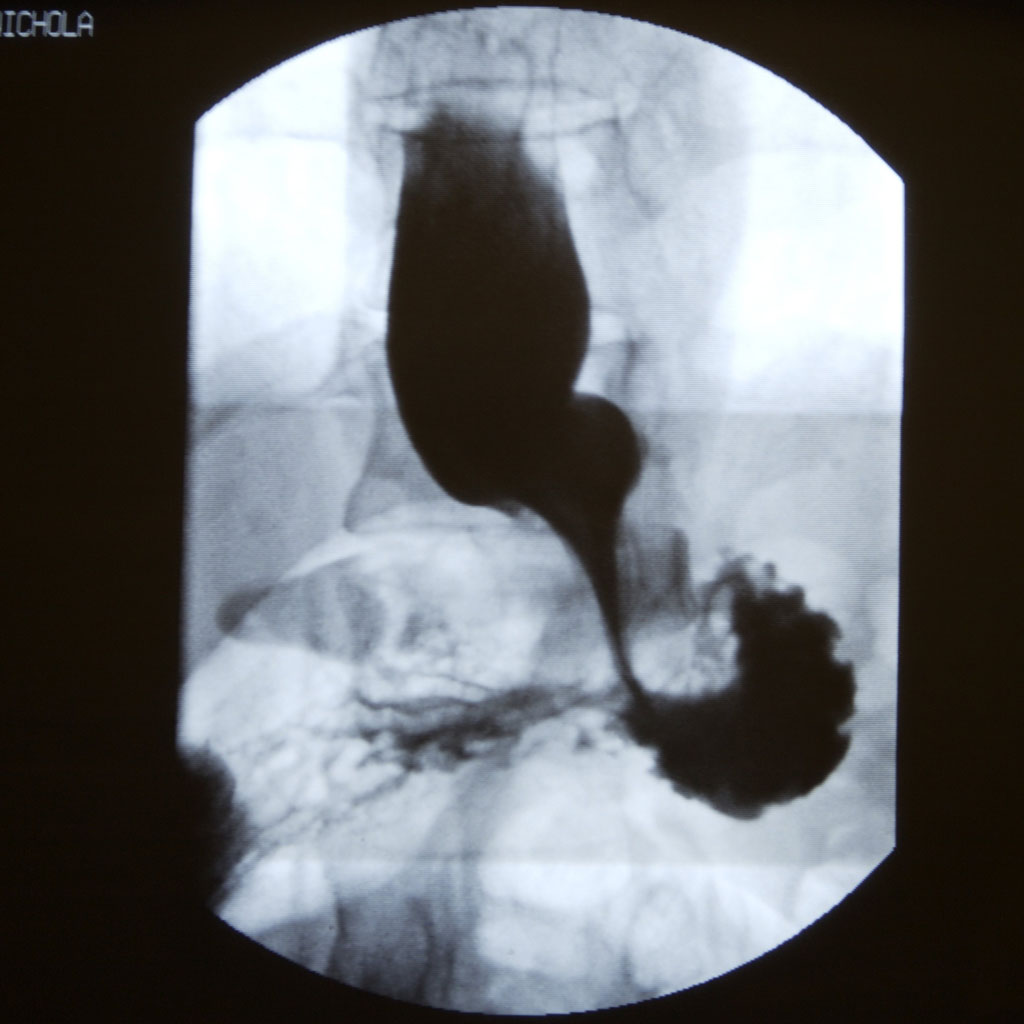

That means an operation like having a gastric band fitted to make the stomach smaller, or a gastric bypass, where the digestive system is re-routed past most of the stomach. Both techniques are designed to make you feel fuller after eating less.

But Nice now says we should lower the bar for recommending patients have surgery. People with a BMI as low as 30 should now be considered for an operation if they have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes over the last 10 years.

And people who are of Asian descent could be eligible for surgery with an even lower body mass index. This is because Asian people are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes at lower weights.

If we extrapolate from the National Diabetes Audit, this could mean an extra 850,000 to 900,000 people being considered for surgery on the NHS.

But it is unlikely that hundreds of thousands of people could get an operation quickly. The NHS says demand for bariatric surgery is higher than supply in many areas of the country, so many patients will be on “a considerable waiting list”.

Balancing the one-off cost to the NHS of an operation (from £3,000 to £15,000) against the long-term cost of health conditions linked to obesity has led some researchers to predict that surgery pays for itself.

Nice’s experts said that bariatric surgery “is highly likely to be cost-effective” for obese people with recent onset type 2 diabetes. The evidence of value for money was weaker for other patients.

Why not go on a crash diet instead?

Some patients with diabetes have apparently had good results after following a very low-calorie diet for a short while.

Professor Roy Taylor from Newcastle University found that a specially designed low energy diet can produce rapid changes in body composition and put type 2 diabetes in remission for some people.

But today’s Nice guidelines say crash diets like this should not be used routinely. They should only be considered “with ongoing support, as part of a multi-component weight management strategy for a maximum of 12 weeks in people who are obese who have a clinically-assessed need to rapidly lose weight”.

Why are we so fat?

Some campaigners are fingering sugar as the key ingredient that is making the world fatter. The campaign group Action on Sugar today called for the government to impose a tax on sugar to try to wean the country off the sweet stuff.

Others say weight gain is about the total calories you take in, and it doesn’t matter whether the energy comes from sugar or other sources.

A recent study by the World Health Organisation backed this point of view, but the WHO has nonetheless recommended that people halve their sugar intake.