How one American family is fighting heroin ‘stigma’

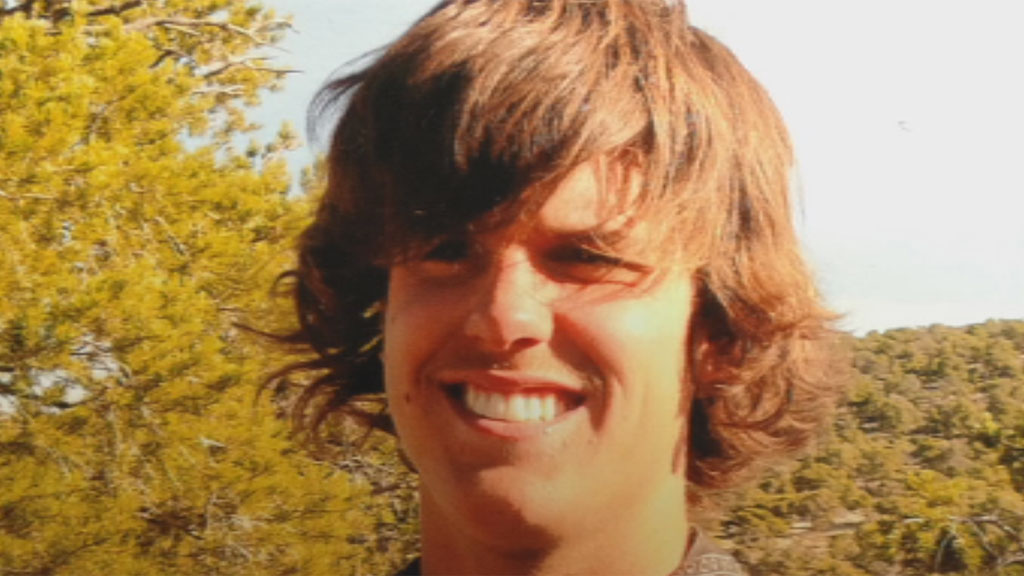

The death of Philip Seymour Hoffman has thrown the spotlight on heroin use among the American middle classes. Emily Wilson meets the family of Chris Atwood, who died from an overdose at the age of 21.

(The Atwood family talks to Channel 4 News)

Going up the drive of the Atwood family home in suburban Virginia has a familiar feeling to it. A beautiful, big American family home with a big porch, lots of land and a basketball hoop outside, two cars in the driveway.

Millions of American homes look like this. But a fraction of them have experienced what went on inside this home. On 23 February 2013, 25-year-old Ginny Atwood came home from work to find her 21-year-old brother dead from a heroin overdose. The pernicious street drug of the inner cities had come to suburban Virginia, and taken a much-loved, creative, funny young man.

The Atwoods have created a foundation that they say is primarily to try to remove the huge stigma attached to heroin addiction. Thirty years after Nancy Reagan told American schoolkids to “Just Say No” to drugs, Anne Atwood says there is still huge misunderstanding in America about the nature of drugs, and of addiction.

Chris was only 14 when Anne says she first started seeing signs that he might have what she calls “mild depression”. She says: “He would go into a funk, blow things right out of proportion.”

‘I knew this wasn’t a prank’

He got involved with some friends who liked to play truant, vandalise the odd thing. But then she found a needle. “He tried to laugh it off, but I knew something was wrong. I knew this wasn’t a prank.”

The family were swift in taking action. Just a few months later Chris had his first period in rehab. He went voluntarily, if reluctantly.

Over the next six years he returned to rehab five times. The longest he was clean was a full year. The Atwoods paid the equivalent of a year’s college tuition to send Chris to a wilderness treatment centre and boarding school in the western state of Utah.

There, teenage addicts hiked, cooked dinner over campfires, slept outside no matter the weather. As Anne points out, most American families couldn’t afford that. But each time Chris returned to normality, he struggled every day with his addiction.

On the white board in his bedroom are still written the notes he wrote to himself during this struggle. Take One Day at a Time. Avoid Bad Habits/Triggers. Evidence of Chris’s daily, hourly struggle against his inner turmoil that those closest to him could never understand.

His father, Mark Atwood, says he’s grateful for the last month they had with Chris, as he’d completed what would be his last period in rehab. He was clean, he was fit, he was eating healthily.

He seemed to have turned things around, as a month before that he had overdosed, but his sister’s boyfriend found him unconscious and a friend revived him with CPR.

That “wake-up call” – as the cliché goes – appeared to have given Chris his latest impetus to get clean and stay clean. But that wasn’t to be.

Heroin use has doubled

Heroin overdoses have doubled in the US in the last five years, as has the number of users. The drug is more widely available than ever before, so as authorities clamp down on prescription drugs, heroin has become a cheaper, more widely available substitute. Heroin users are younger and more middle class.

Rusty Payne, a spokesman for the Drug Enforcement Administration, described the spike in heroin use over the last few years as “an epidemic.”

For Anne Atwood, the use of a medical term like “epidemic” is the right way to frame the new debate over heroin’s grip on America.

“People said to me after Chris’s death, ‘Didn’t your son’s school educate him about drugs?’ And I said, ‘I educated him about drugs!’ This isn’t a bad education, it’s not a lack of morality. This is a health issue.”