How fair is public sector pension reform?

Lord Hutton, author of a new report on public sector pension reform, tells Channel 4 News fairness is a key aim – but others say the system remains so unfair it will need another review in five years.

Lord Hutton’s independent report into the future of pensions for public sector workers suggests a major shake-up across the board, from the age at which public sector workers can retire to how their pensions will be calculated – based on average earnings, rather than their final salary.

The Government will now consult on and consider his recommendations for reform, which aim to strike a “balanced deal” between public sector workers and the taxpayer at a time when the population is living longer.

My argument today is not all about affordability…it’s in equal measure about affordability and fairness. Lord Hutton

Launching his report into public sector pensions today, Lord Hutton told Channel 4 News: “My argument today is not all about affordability, although we can’t ignore that issue. It’s in equal measure about affordability and fairness as well.”

Fairness

As Economics Editor Faisal Islam found, costs of public sector pensions are not set to rise inexorably but will instead fall from the 2030s. So based on affordability alone, there is not necessarily a need for reforms which could well cause major industrial strife and actions from disgruntled public sector workers.

However, Lord Hutton said fairness was equally important in two respects – one, to make things fairer for the taxpayer, and two, to make the system itself fairer for public sector workers who earn different amounts.

But Michael Johnson, at the Centre for Policy Studies, told Channel 4 News the system was so mired in “innate unfairness” for taxpayers that the entire issue of public sector pensions would have to be revisited again in five years.

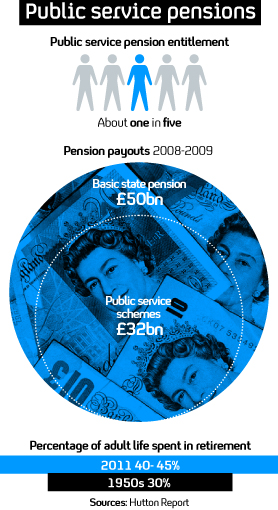

“The key fairness issue here is, assuming the reforms are implemented, that the 20 per cent of people who work in the public sector will continue to have certainty of income in retirement until they die,” he said.

He points out that, instead of funding pensions that are paid out for longer as life expectancy grows, public sector workers are being bailed out by tax payers, many in the private sector, who do not have such benefits themselves:

“The real concern here is that we are going to have to revisit this subject in five years’ time because of that innate unfairness.”

Shortfall

He said the main concern was the shortfall between the amount of money paid into the public sector pension pot, and the amount that needed to be paid out. Five years ago this was £200m. Now, its £4bn. In five years it is expected to be £10bn.

We are going to have to revisit this subject in five years’ time because of the innate unfairness. Michael Johnson, Centre for Policy Studies

Lord Hutton has tried to deal with this issue in the report by suggesting higher contributions – which some fear could see more people opt out of the pension scheme altogether. The Government has already announced one step to tackle the gap, a three percentage point increase in contributions across the public sector, phased in over three years starting next year to raise £2.8bn. Pension pay-outs have also been changed so that they are now linked to CPI-inflation, rather than the generally higher RPI-inflation.

Public sector pension reform: a recipe for strife

But Mr Johnson does not think this goes far enough.

“This gap is entirely filled by the Treasury, which is paid for by taxpayers,” Mr Johnson said.

“Hutton will reduce that gap but only by a small amount – so the other £8bn or thereabouts will have to be found from the Treasury or other taxation. Hutton has gone as far as he can in the current situation because his hands are tied, but it does not create long lasting reform which is what we actually needed – as the biggest problem is a lot of people are living longer.”

He said the system could only be fairer if the state pension amount was raised.

“An essential pre-requisite to fixing this is to raise the state pension above the poverty threshold because then the legitimacy of the unions’ concerns for pensioner poverty disappears. It whips the carpet from under their feet, and then we can go about genuiunely moving to a new system,” he said.

Fairness within the public sector workforce

Lord Hutton also said his reforms would address serious concerns over fairness within the system itself, for public sector workers.

At the moment, he said that the highest-earning fifth of Local Government Pension Scheme pensioners get almost a third more in pensions per £100 of contributions than the lowest-earning fifth – and around half of pensioners receive less than £5,600 a year.

“My principal argument for changing from a final salary scheme to career average scheme is a fairness argument,” he told Channel 4 News.

“That in itself is not going to reduce costs, not necessarily so. In fact it could re-distribute benefits towards lower and medium earners, and that’s where I think the focus should be.

Read FactCheck: Should we feel sorry for public sector workers facing pensions squeeze?

“I think we should end the hidden cross-subsidy that currently exists in final salary schemes where those on low pay subsidise the high pensions of those at the top. That’s just simply not fair.”

Low and high flyers

His claims were backed up by KPMG‘s Head of Pensions in the UK, Andrew Cawley, who told Channel 4 News that the shift to a career average scheme would benefit lower earners.

This is because the report proposes that earnings in each year of an individual’s membership of a public service pension scheme should be revalued in line with the national average earnings growth. For people who earn more than the average, this is less generous – but to those whose salaries grow by less than average earnings, the revaluation makes the scheme more generous than a final salary scheme.

“Anyone who earns more than the national average is defined as a high flyer, anyone who earns less is a low flyer,” he said.

“It’s an interesting surprise that the indexation proposed by Hutton is in line with national average earnings – what that has done is redefined high and low flyer, and made the changes more re-distributive towards low flyers.”

However, while this did still mean that lower earners would be better off comparatively with higher earners, all public sector workers will “feel the pain” of other changes, he said.

Public sector pension shake-up

“The change in the national pension age and the change from RPI to CPI payments means that on balance it is going to be worse,” he said.

So the system probably will make things fairer for lower earners, although the Institute for Fiscal Studies warns that there is not enough detail yet to calculate the possible winners.