Iraq 10 years on: the faces of change

Andy Davies

Home Affairs Correspondent

Andy Davies

Home Affairs Correspondent

Blindness, bereavement and post-traumatic stress disorder. Andy Davies meets three people whose lives have been forever changed by the decision to go to war in Iraq a decade ago.

‘My whole world fell apart’

Simon Brown was on his second tour of Iraq as a vehicle mechanic with the Royal Electrical & Mechanical Engineers when he was shot in the face by an Iraqi sniper.

It was the 6th December 2006. He and his colleagues had just recovered a stranded vehicle while out on patrol. With dust making visibility poor, he popped his head out of the top of the turret to shout “Clear. Go!” when he suddenly felt the “smack on the side of my head” and then, as he describes, “the whole world around me disappeared”.

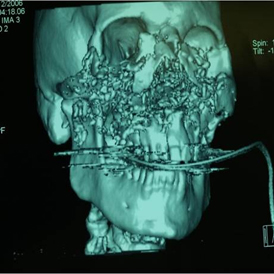

A bullet from an AK47 rifle had entered his skull just below his left eye and torn through his face, exiting below his right eye. He was taken out of Basra within 36 hours and flown back to hospital in the UK. He was in a medically-induced coma for 17 days.

The optic nerve of his right eye had been completely destroyed; the retina on his right eye crushed “like a squash ball”. His jaw had been broken in four places. When he came round from the coma he recalls being told that he was blind: “My whole world fell apart”.

For several days he contemplated saving up his medication and killing himself.

It was the news that two of his friends had died in Iraq which proved a turning point: “That was the kick I needed … I’m not going to abuse their memory by wasting the opportunity I’ve got still being alive … that was the catalyst for me to try and rebuild my life”.

After 15 operations and 120 hours of surgery Simon has recovered many of his facial functions, but he has no sense of smell, partial paralysis around his eyes and only 15 per cent peripheral vision from his right eye. His recovery, although slow, has proved inspirational for many other blind veterans.

Having volunteered to work with young offenders for two years, he now works for the charity Blind Veterans UK as a membership officer. He is working full time and feels mentally enriched by the challenges thrown up since the events of December 2006: “When I look back now over this 10 years I think, you know, I didn’t choose any of it, I didn’t pick any of it to happen, but now I’m very proud of who I am and I think in a way I’ve probably achieved much more than I ever could have achieved had it not happened but I’m very proud of what I’ve done”.

A ‘wonderful’ husband

Raqual Harper-Titchener became a war widow aged 28 on Saturday 23 August 2003. Her husband Major Matt Titchener was serving with the Royal Military Police in Basra when he, Warrant Officer Colin Wall and Corporal Dewi Pritchard were ambushed and killed by Iraqi insurgents. Raqual was 20 weeks pregnant at the time with their second child Angel. Their son Matheson was just two years old.

For Raqual the tenth anniversary of the invasion of Iraq has added poignancy: “Matt and I were together ten years and I’ve always dreaded that moment when he’ll be gone longer than we were together…it’s difficult as well to think he’s been away from us for that length of time and we are still moving on.”

Raqual plans to travel to London this year for Remembrance Day. She’ll take Matheson and Angel with her, children who “live and breathe” their father, says Raqual.

Matheson, an avid Liverpool FC fan like his Dad, tells me: “I hope we can get in the parade and just feel proud of my Dad”. Angel laughs when explaining how they always eat McDonalds on the anniversary of Matt’s death, his “favourite meal”.

“What do you think of the job your Dad did?” Raqual asks nine-year-old Angel. “Good but probably a terrifying job,” she replies.

“You have to make them aware that Matt was a great Dad” says Raqual. “He loved them to bits … they just have to remember he was always there and is always going to be a presence for them. (They) just have to make him proud of what they’re doing: live their lives, be generally good people and appreciate what’s around them.”

Raqual, who remarried last year, describes the last decade as a rollercoaster ride, ameliorated by the “great support” she has received from the Army Widows Association, among others.

On the war itself, she refuses to be drawn into the politics of the conflict: “Regardless of whether I believe the war was right or wrong is totally irrelevant … If I was to go into all the rights or the wrongs and take all that on board I think you could become bitter, very lost in all that, and you lose what really is important and that is the fact you’ve had such a wonderful person in your life…I think to respect their memory you need to focus on that and try and be positive.”

A ‘pointless’ war?

James Price joined the Grenadier Guards straight from school aged 16. By the time he left in 2011 he’d served one tour in Iraq (2006) and one in Afghanistan (2009). He left the army in 2011, unemployed, his marriage disintegrating and diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

He describes being in a wretched state and afflicted by a debilitating sense of a confused identity: “I would look in the mirror and I would see a person – I don’t know who that person was – I just saw a person. I knew it was my reflection but I’m looking in the mirror going ‘who are you? What are you? What are you doing?’ I just didn’t recognise myself.”

The depression was acute, as were the flashbacks and nightmares. He describes some of the events which he heard rather than witnessed (principally in Afghanistan) as major factors in triggering his PTSD. He was particularly affected by the death of his Sergeant Major.

According to the Royal British Legion, James is a fairly typical example of many of the soldiers they support. In the last year they’ve provided him and his partner with a new cooker, carpets and £200 of Sainsbury’s vouchers.

Combat Stress, the veterans’ mental health charity, has also been providing support for James. He is off medication now and trying to get a license as a security guard, slowly rebuilding his life.

James says he has no regrets about his time in the military but he remains confused about the rationale behind the Iraq war: “I think it was a pointless tour. I don’t think we were out there for the right reasons … it wasn’t our war.”