Is ‘militant secularisation’ a threat to Britain?

The British Humanist Association tells Channel 4 News Baroness Warsi’s description of secularists is “an astonishing smear” – but Christians say they are victims of a growing intolerance.

Baroness Warsi’s comments about a growing intolerance towards religion have been met with anger among humanist and secular groups.

In much publicised comments Baroness Warsi warned, ahead of a visit to the Pope in Rome, that religion is being “sidelined, marginalised and downgraded in the public sphere”.

Her claims come shortly after the government mounted a heated defence of Christianity sparked by the ruling against prayer sessions in council meetings. Communities Secretary Eric Pickles said it was time to defend “British traditional Christian culture”.

But is Britain really a Christian country? The last figures available on what religion people consider themselves to be are from the British census of 2001. When asked, what religion are you, 72 per cent (42 million) described themselves as Christian, 15.5 per cent as no religion (9.1 million) and 2.7 per cent as Mulsim (1.6 million).

Real Christian beliefs?

One group, campaigning for less influence of religion on public life, is arguing that religious belief is not as widespread as these figures might suggest.

In a survey conducted for the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science, Ipsos Mori questioned just over a thousand people – all of whom said they would be listed as Christians in the latest census.

The foundation claims that identifying as a Christian did not correspond to a real belief in Christianity. Only a third cited religious beliefs as the reason they ticked the “Christian” box in the census.

The research also suggests that even people who identify as Christian are opposed to the influence of religion in public life. Three quarters agree that religion should not have special influence on public policy and nearly half oppose the idea of the UK having a state religion.

‘There is a lot of nominal Christianity in Britain’

Nick Spencer is research director at Theos, a Christian public policy think tank. He thinks that people’s religious beliefs should not be so easily dismissed. He told Channel 4 News: “There is a lot of nominal Christianity in Britain. Their beliefs will be a bit flakey, but I have spent time interviewing people who were non-practising religion, half of whom were nominal and half had not ticked – there was a real difference between them. It is still significant.”

A small minority are using human rights legislation to sweep religion into corners. Nick Spencer, Research Director, Theos

He argues that there is a move towards forcing people to leave their religious beliefs at the door of public life, which is undemocratic.

“She (Baroness Warsi) is on to something with regards to the vocal presence of a small number of exclusive secularists. A small minority of people are trying to use human rights legislation in order to sweep religion, particularly Christianity, into corners.

“A free and democratic society is marked by the fact that people feel able to engage in public life for their own reasons.”

‘Disproportionate role’

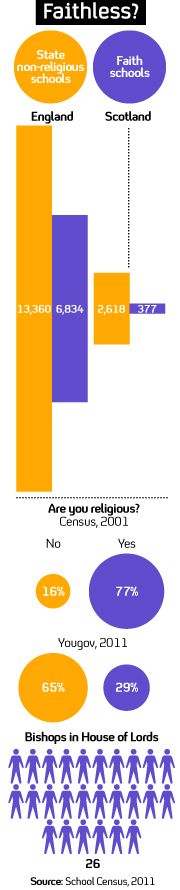

Both the last Labour government and the present coalition have pushed for more involvement of religious groups in state business. There has been an increase in the number of faith schools, and David Cameron has made clear his desire to see more faith groups delivering services.

Warsi’s talk about illiberal sectarianism is a cover for driving through pro-religious policies. Andrew Copson, British Humanist Association

Secular thinkers say that this is a worrying trend. Andrew Copson is chief executive of the British Humanist Association. He told Channel 4 News that far from religion being swept into corners, it has a disproportionate role in public life: “There are fewer and fewer religious people but ironically the government is driving in the other direction.

“Warsi’s talk about illiberal sectarianism is a cover for driving through pro-religious policies. People like the Archbishop of York love to weave this false narrative of persecution of Christianity as a way of hiding their own privileges and power.

“Surveys show again and again that the public are against state funded faith schools. The contracting out of public services is an even bigger issue. Religious groups can discriminate in employment, so if you are working in a care home and it is contracted out to a religious group you can find your prospects limited.”

Nick Spencer draws a distinction between ways that secular influence can work: “There are two different kinds of secularism – one is inclusive, it says come onto the playing field, we will make sure it’s level and there is an exclusive secularism that says you can only come if you play in our strip.”

But for Andrew Copson, it is Baroness Warsi who is not being inclusive. Referring to her comment about ‘militant secularisation’ he said. “It is an astonishing smear and a totally inappropriate one for a minister who is supposed to be inclusive.”