Lou Reed: lifelong rebel who made weird cool

Rock musician Lou Reed has died, aged 71. Our Culture and Digital Editor Paul Mason looks back at the moment the Velvet Underground frontman changed music.

If I trawl my memory for Lou Reed, I see myself in a student bedsit in the late 1970s. Way after midnight. Sharing toast and roll-ups with a bunch of friends sitting on a greasy carpet. Lou Reed on the record player and probably some poor ordinary Joe below us trying to get to sleep.

And an argument. About Nico. Before the internet, all you had to go on for knowledge about rock musicians was their album cover notes and the NME. So I can remember there being a big discussion as to whether the Velvet Underground’s female singer Nico was even in the band.

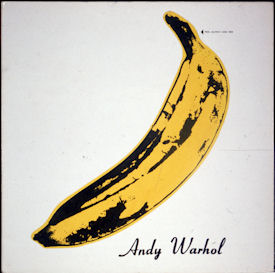

By then, the now famous album cover, with Warhol’s banana, was a badge of belonging for all would be deviants at Sheffield University, and probably every university in the world. You had to have it, or know someone who did, and know why it was brilliant.

Today, Reed’s death makes me want to physically take hold of YouTube and force it to display all music videos chronologically: labelled BVU and AVU – before and after Velvet Underground.

Because while YouTube keeps rock legends forever young it also, for young people now, relegates them to general historical time. Lou’s videos, in rough monochrome, sit there vaguely in the same era spanning the Stones and Roxy Music.

No, to understand what was great about Velvet Underground you have to place it precisely alongside what came before and after.

Before that album came out, pop music was veering towards some kind of rebellion. The Beatles’ Revolver had been released in the summer of 1966, full of quaint, troubled lyrics and classical music references. The Beach Boys had released Pet Sounds – which may sound sugary now but stuck people with its introspective, drug referenced lyrics.

Well if you want to do an instant Spotify DIY musicology lesson, try playing Eleanor Rigby back to back with Venus in Furs, or All Tomorrow’s Parties.

This was music not just troubled by drugs and the breakdown of the sixties dream: it was fuelled by them. It was music for and about people who had been lurking on the edge of the 1960s, guessed at but unknown until now: weird, cross-dressing, heavy drug using, ultra radical.

It was not the rebellion coming, it was the rebellion arrived.

It was not the rebellion coming, it was the rebellion arrived. And even then it was ahead of its time. As the Berlin meme arrived in the early 1970s, those early Velvet Underground tracks, and videos, looked like they had defined the scene. None of the musicians would have looked out of place among the Baader-Meihnof gang and its thousands of wannabe followers.

The album also, with hindsight marks the entrance of contemporary art into pop music. Reed’s band was managed by Andy Warhol and pulled into a vortex of creative interaction – if you can call the chaotic stuff they did that – with Warhol’s experimental world.

Now if you play any of the big albums of 1967-68 you can see that, whether influenced by the Velvet Underground and Nico album or not, they were part of a world that had hinged around it. Jimi Hendrix makes Are You Experienced, the Doors make The Doors, the Grateful Dead album comes out.

All these bands looked and sounded weird, and soon they looked no weirder than reality. The global revolt of 1968 happened and the Velvet Underground’s music was, in places, its soundtrack – becoming weirder in the second album, with long tracks and experimental guitar sounds…

And then they’d gone. Reed’s solo career seeded the careers of the musicians who worked with him: Bowie, Wakeman etc. And there is a clear lineage between Reed’s music and the music we were listening to in the mid-1970s.

When rock music got tired of being macho and long-haired, and wanted to be deviant and rebellious, people dug out their copies of that album with its yellow banana sticker and weird female singer nobody knew anything about, but everybody would have liked to have known.

But Reed was not great for being a punk 10 years before John Lydon, nor a glam rocker seven years before Bryan Ferry. He was great for being a lifelong rebel, dedicated to music as the celebration of the painful, the decadent and the transgressive.

As I write this I hear his voice on the radio saying: “I don’t care about my career. I don’t care about the music business. I’m not a businessman.”

No, he was a rebel and stayed one.