Pride and hardship: miners share memories of 1984 strike

Andy Davies

Home Affairs Correspondent

Andy Davies

Home Affairs Correspondent

In 1984 south Wales miners joined a nationwide strike. Andy Davies meets strike veterans taking part in an anniversary exhibition who, despite the outcome, have fond memories of the event.

“It was the best year of my life” says Alan Sandel, recalling the events of 1984 when he walked out of Celynen North colliery in south Wales and joined the massed ranks of the picketing miners. It would be a year before he would return to work, by which time Britain had witnessed a defining, deeply scarring moment in the history of industrial relations.

Margaret Thatcher had taken on and defeated the unions and, within months of returning to work, Alan’s colliery was closed down. It was a similar picture of rapid decline across the British coalfields, the deep economic and social consequences of which are still being felt today.

In a project commissioned by the National Library of Wales, Alan Sandel, now 75, is one of the ‘faces’ of the strike being photographed 30 years on.

Familiar ground

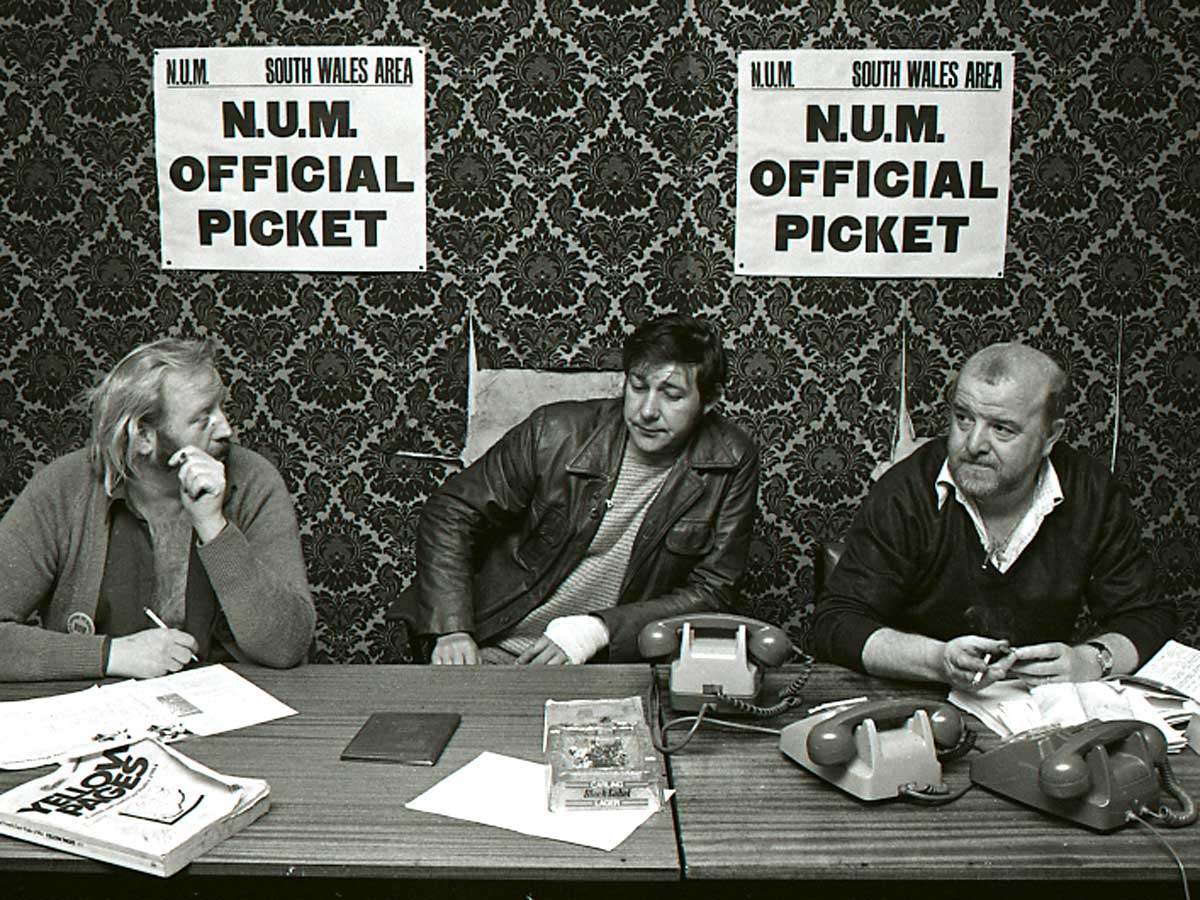

The man behind the camera, Roger Tiley, is also back on familiar ground. As a young press photographer working in south Wales for titles such as the Times and Guardian, Roger witnessed the strike at close quarters, documenting a period in which the miners emerged from the pits to take on the state. His archive catalogue offers a rich portrait of a struggle which, over a year, saw communities almost permanently mobilised in collective resistance.

Now he is retracing his steps, photographing again the people he encountered during the strike: “Going back is an incredible experience and the nice thing about the project now is I can speak to them, I can get to know them… I think they won to be honest, because they showed pride, they held their heads up high, so I think you know I was privileged to witness that.”

In Newbridge’s ‘Memo’, a hall built by the miners of the area more than 100 years ago, Alan Sandel is joined by Dot Phillips, Angela Boulton and Donna Barnes, women who formed part of a formidable local support group during the strike. At the Memo, then strike headquarters, they were making corned beef pasties and chips, says Dot, on a daily basis, feeding scores of miners returning from the picket lines. They recall the door-to-door collections, the raffles, the enduring enmity of some directed at those who broke the strike, and the hardships of a year in which wages went unpaid.

Empowerment

But in the defeat which ultimately came, as Dot explains, there had also been empowerment: “Despite the result, I think that we did a good job as women, and I think we had reason to be proud of ourselves, and the whole thing gave us a lot more confidence in ourselves.”

For Alan Sandel, the strike may have achieved little but at least it brought respect, he says: “I think it did give respect for the area that you were willing to fight for what you thought was right.”

Respect perhaps, but in the end it was a resounding defeat. By the time of the strike in 1984, following decades of pit closures, there were 20,000 miners working across the South Wales coalfield. Now there are barely a few hundred. Thirty years on from that tumultuous last stand, this is a land that has lost the industry which once defined it and is still dealing with the legacy of that loss.