Four days in North Korea – a ‘chasm’ away from rest of world

Accused of insulting “the people of the nation” before rendering his minders speechless – Asia Correspondent John Sparks reports from inside North Korea.

At first sight, it looked like we had been taken to a giant sculpture park, but it was not, however, an exercise in outdoor art. It was an oversized shrine to the North Korean military in the heart of the capital Pyongyang.

The forecourt of the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum is decorated with colossal Soviet-style art, depicting battle scenes from the Korean war. Further on, the authorities have thrown up a hulking museum, constructed in an impressive 12 months I was told.

The complex is flanked by pavilions displaying North Korean armaments and I asked myself a simple question – how much did all this cost? In a nation that struggles to feed its own people – something North Korea blames on international sanctions and western hostility – it seemed an extraordinary use of resources. A few subtle enquiries to our two minders – “numbers one and two” – produced no results so I recorded a piece-to-camera where I gently questioned the expense. Well that was met with blind fury from minder “number one” who accused me of insulting “the people of the nation”. He stormed off in a huff.

I grabbed my cameraman and prepared to do a ‘doorstep’ – an unscheduled interview.

Still, our afternoon had only just begun. The North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un turned up and inaugurated the museum in an outdoor ceremony. Minutes later, he turned on his heel and headed into the museum for a tour along with his entourage. Ten minutes later, international media were invited to follow and my cameraman Matt Jasper and I joined the crush.

We were met in the museum’s cavernous lobby by a monumental set of stairs, topped off with a super-sized statue of Kim ll-sung. He was both the founder of North Korea and Kim Jong-un’s grandfather – and he is revered by many here as a god. Perhaps that’s why we couldn’t stand on a plush bit of carpet directly under the statue.

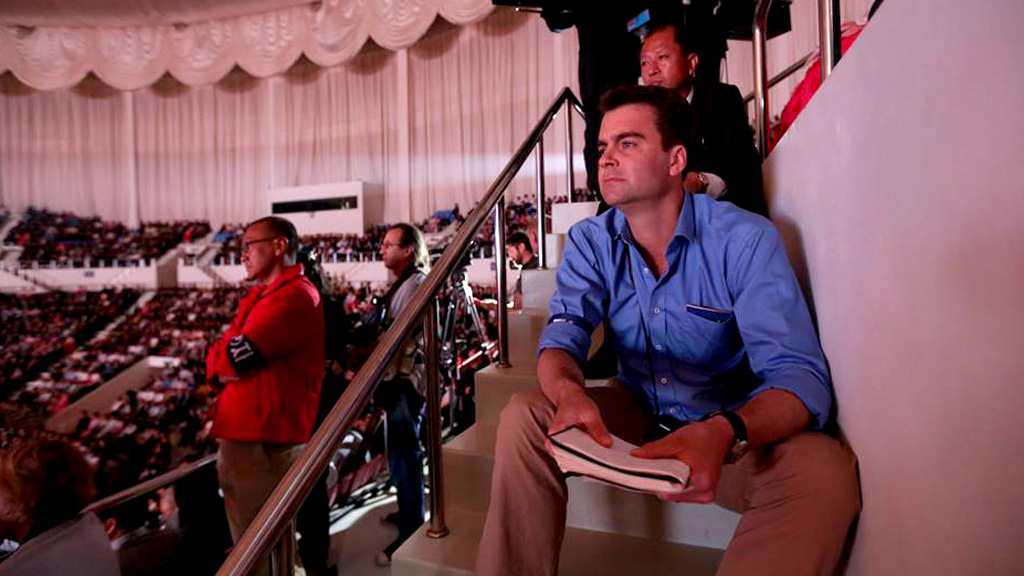

By this point we had lost all contact with the current leader, so we headed into one of the far small exhibition rooms. Sometime later, I then noticed some clapping out in the hall and thought to myself, that couldn’t be him – could it? We have been carefully marshalled on this trip, not just by “numbers one and two” but by an entire battalion of media minders and coach drivers. We have been able to film Kim Jong-un from a distance but we’ve never be allowed to get that close.

‘Minders one and two looked stunned’

Well, when I peeked my head round the corner I could see the man they call the Generalissimo heading our way. I grabbed my cameraman and prepared to do a “doorstep” – what the people in my trade call an unscheduled interview. The crush of people in the hall almost knocked my sideways but we held our ground.

“Kim Jong-un, Channel 4 News, UK,” I called out. He gave me a look but kept on walking. I kept going; “what’s your message to the west?” I asked.

It seemed an appropriate question after spending the entire morning watching the largest military parade of earth. This public display of firepower along with the squadrons of near-hysterical citizens pledging their loyalty to the regime was designed to make a definite impression – an impression of strength at home and abroad.

Needless to say, Kim Jong-un kept walking and we heard a large cheer go up as he re-entered the lobby dominated by his grandfather’s statue. I turned around to see “numbers one and two” and for the first time on our trip, they were speechless. I don’t know if it was the fact that I had asked the “great marshal” a question – or because they had found themselves so close to him but they looked stunned.

We still had work to do however. A large number of foreign guests had been invited to the museum opening and their presence there suggested they were valued friends of the nation – and that made me curious. North Korea is both isolated and subjected to a wide range of international sanctions so I wanted to know what they were doing here.

Their reaction was telling. Some were indignant and stormed away. Others were shuffled on by their minders. One man from a South Asian delegation was willing to chat and offered a simple commentary on the museum; “it is a piece of history for the people of North Korea, it’s very opulent you know”.

When my cameraman moved back however, he leaned in and uttered, “completely despotic government – very offensive”.

I admire the North Koreans for being brave enough to let people like me in but we cannot stop being journalists.

The worst encounter we had was with several gentlemen from France. When I asked one of the linen-suited men whether he was representing the government, he tried to rip the camera from my colleague’s arms.

What does it all tell me? Well, I think the bridge between North Korea and the rest of the world (with the exception of a few countries like China) is so chasm-like that a simple exchange of views will likely result in anger, bewilderment and disappointment.

I admire the North Koreans for being brave enough to let people like me in – and they deserve credit for it – but we cannot stop being journalists because we are the privileged holders of a North Korea visa.

Where there is engagement between North Korea and the west, I think it is safe to say that it will take place in the shadows, where witnesses are scarce and records are rarely taken.