What snoopers can see from your clicks and searches

After the Prism spying scandal exposed the vulnerabilities of our online data, we sent the Channel 4 News Data Baby to an information security company to find out the extent of her online footprint.

Logging on is now one of the first things we do every day. And every time we do, we leave a trace, often without giving a thought to the information left in our trail.

The reason the Prism spying scandal has had such a big impact is because it hit home just how much of our information is being gathered online and sent to US-based servers – and what it would reveal if it could all be accessed by an all-seeing Big Brother-esque government agency.

For the last three months, Channel 4 News has been looking into this issue through the Data Baby by creating a virtual identity online, every trace of which can be forensically analysed and tracked.

Our “Data Baby” is called Rebecca Taylor: she is 27, lives in London, likes travel, music, fashion and uses all the popular social networks. In reality, Rebecca is a laptop which Channel 4 News controls, guided by the personality type we have made for her.

The full extent of the US government’s access to nine major internet companies’ servers is up for debate. The companies still dispute the direct “back-door” access claims. And yet when briefed on the NSA’s surveillance programme, one senator said that what had appeared in the media was “the tip of the iceberg”.

Following the revelations, Channel 4 News sent the Data Baby to MWR Info Security to see what the company – and anyone who has the access – could find out about Rebecca Taylor, purely from her online activities.

What you like

Under EU law, security agencies need a court order to access browser history. But Google and Facebook keep track of the websites we visit when we are logged in. That is how they know if you are pregnant, or newly engaged – and show you adverts that are tailored to your life.

MWR consultant Guillermo Lafuente was able to download a list of Rebecca’s “ads topics” from Facebook, indicating her interests based on sites that she had visited.

Some of the topics were things that Rebecca had talked about or “liked” on Facebook: Cupcakes, The XX, Daft Punk, Yahoo! and Latitude Festival, to name a few. (She is a 27-year-old Londoner after all).

It is really important to remember that any data you post or send online can in theory be accessed forever – MWR consultant

But other topics collected as data by Facebook include the Republic of Ireland, “Pub” and “News”, all of which were collected based on her browsing history.

Even without Google and Facebook keeping tabs on our searches, we willingly provide a huge amount of information publicly that is up for grabs to anyone who wants to know. Mr Lafuente was easily able to compile a list of websites that Rebecca had linked to on Twitter, including Pinterest pictures, Asos clothes, the Independent newspaper and MySpace pages.

And considering that prosecutors often use web history as evidence of motivation in court and websites gather this info as valuable data to sell on to marketing companies, this is hugely valuable information.

Read more: Key questions on the Prism spying scandal

Location, location, location

On most social networks, you can choose whether your post is tagged to a specific location. But even though we had turned Rebecca’s location data off, MWR was able to locate exactly where she had logged on at specific dates and times, and for how long.

It was soon clear that Rebecca is a creature of habit: she tends to log on in the afternoons, often during a lunch hour, and later in the afternoon on weekends – valuable information for marketing companies, let alone security agencies.

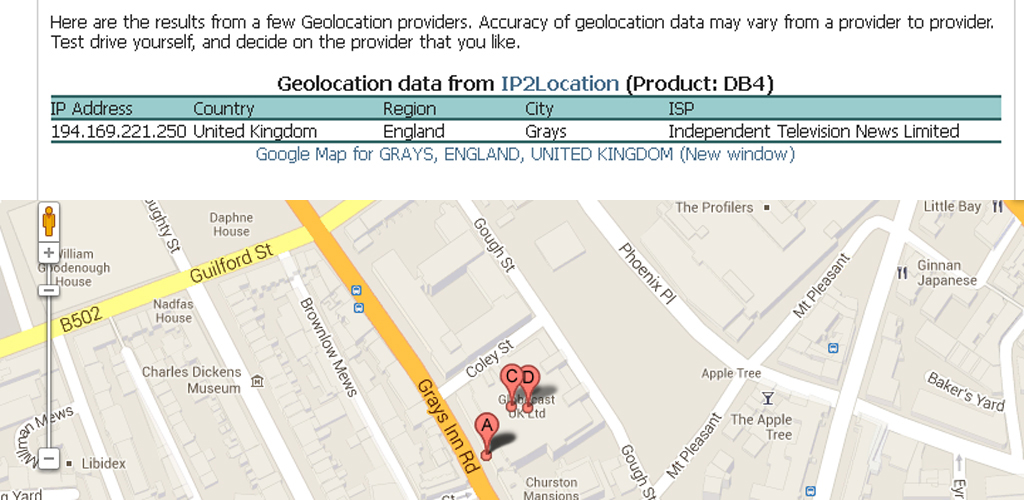

And sure enough, an IP address from one Facebook session on 10 April tracked Rebecca directly to ITN, Gray’s Inn Road, where Channel 4 News is based and where much of the Data Baby online surfing takes place – even though the laptop is never logged on to the company wi-fi.

But as well as the IP address, Facebook also makes it really easy for anyone who wants to know: rather than having to go to another website, the company logs an “estimation location inferred” from the IP address.

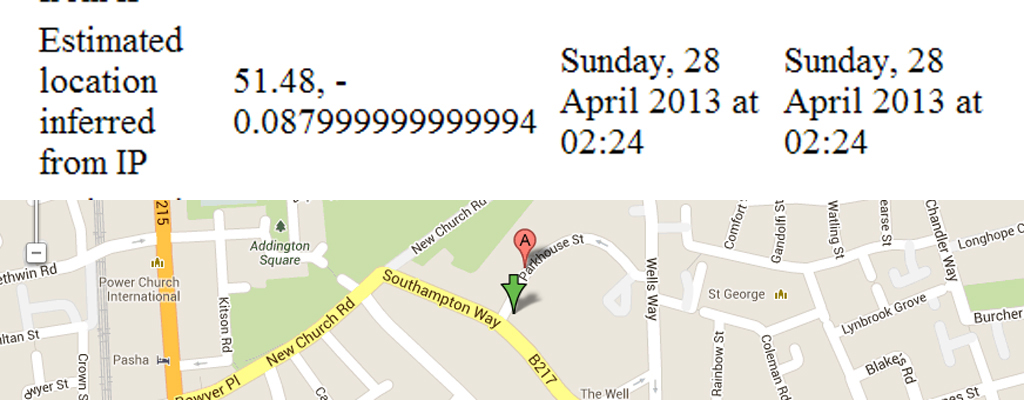

So the MWR consultant was able to say that on Sunday, 28 April 2013 at 02:24pm, Facebook had “inferred” that Rebecca logged from “latitude 51.48, longitude -0.087999999999994” – or Camberwell, south London, to you and me, near to where one of the team logging on as Rebecca is based. Another showed her progress to Brixton, and to West Croydon, where various members of the team were logging on.

Of course, using an outside wi-fi connection immediately means that your location can be traced. But when location is already stored by the sites we visit – and when it comes to Facebook, in a readily available format – that makes it very easy for anyone with an interest, and access, to take a look.

Friends like these

The NSA’s defence of the large scale collection of Verizon phone records consisted of pleas that it is “just” meta-data – or the data about the data – rather than the content of calls, that is collected.

Through the meta-data stored by Gmail, Mr Lafuente was able to see anyone who Rebecca had been in email correspondence with, and the time the emails were sent and received. The data was compiled in a .json file, which according to Mr Lafuente, makes it very easy to process.

Email content is the holy grail for snoopers, and access to it will be permitted by courts if security agencies make a good enough case.

But meta-data is still very revealing. For instance, Gmail data showed that Rebecca had emailed Cashplus properties about a cashless credit card. It revealed which companies she had signed up to for mailing lists and which social networks she was signed up to – through which further information could be gathered. Gmail metadata also provided information about Rebecca’s Google Plus, and Google Reader accounts: everyone she follows, posts she liked and her subscriptions.

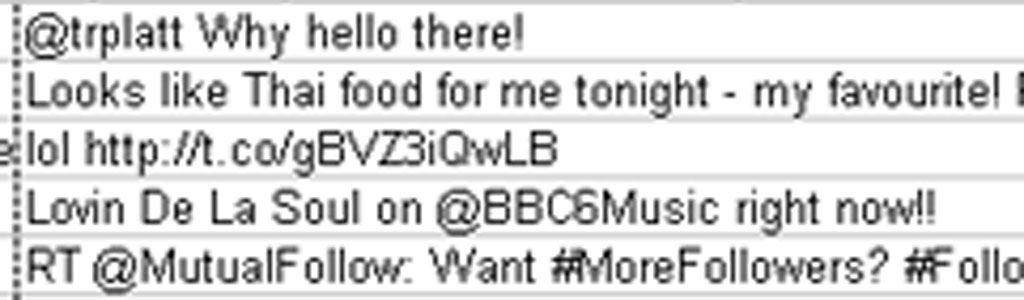

Also, by accessing Rebecca’s Twitter data, Mr Lafuente was immediately able to see patterns in the conversations she had had with certain individuals, and when (see screengrab, right).

Twitter refused to be part of the Prism programme and the company has a history of being reluctant to hand over data. But if a security agency gains a permit, it can download everything you have ever tweeted, and to whom, in an easy to navigate spreadsheet.

What you look like?

Facebook’s facial recognition feature, which allowed it to suggest which friends to tag in photos, has proved controversial. The company was forced to withdraw the feature last year and has deleted its EU database of facial-recognition “templates”.

But earlier this year, the company announced that a new version of the feature was going to be re-introduced, starting first in the US.

Facebook still holds a facial recognition folder for Rebecca, though the data is “unavailable”. In theory, this would take the form of an algorithm that extracts facial features from images, said Mr Lafuente.

“The data would probably look as a string of data that could be processed and compared with other strings in order to identify a person,” he added.

It is worth noting that iPhoto and other applications also use facial recognition data.

Read more on Technology Producer Geoff White’s blog: Who is watching you?

A virtual life

MWR was able to discover where Rebecca is most often based, where she logs on – and when. They found out who she emails, what websites she visits, where she shops and how she pays for it.

But this is all information we can readily access ourselves – and information we willingly hand over every day.

“The theory is that everything we are able to download about ourselves, is pretty similar in quantity to what the government could access,” said Mr Lafuente. “What could change is the format: we don’t exactly know how they process that, but they probably have some kind of software.”

In the coming days, Channel 4 News will publish a guide to keeping your data safe, in collaboration with MWR.

But Mr Lafuente sounds a warning note: “There are programmes you can download to help encrypt your data. But if we’re talking about high level security agencies like the government, they can in theory, get straight to your computer.

“It is really important to remember that any data you post or send online can in theory be accessed forever.”