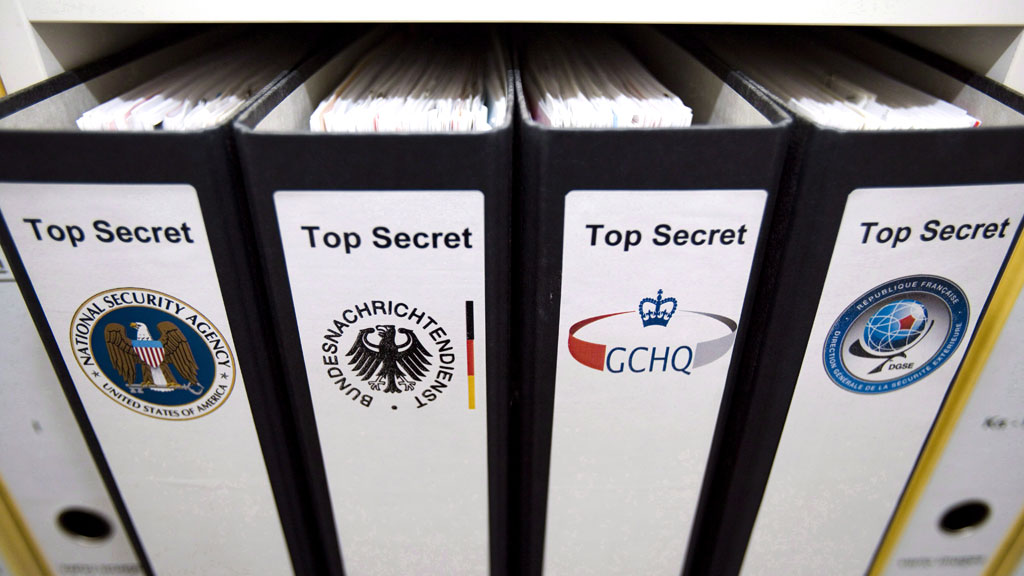

‘Someone should be watching Big Brother’ – GCHQ in court

In a week where the NSA admitted tracking mobile phone locations, the solicitor behind a legal challenge against GCHQ tells Channel 4 News surveillance is understandable – but we need to regulate it.

There is still a lingering sense of confidence that the British state will do the right thing: that is why we have not seen the same sense of outrage over the extent of GCHQ’s surveillance as we have in the US and Europe, says solicitor Daniel Carey.

Whether that trust is well founded, is up for debate. But regardless, Mr Carey says that any state surveillance urgently needs to be regulated – something he says does not exist.

“People may be comfortable that ‘Big Brother’ is watching them, but I think we can all agree that someone should be watching Big Brother,” he told Channel 4 News. “And at the moment, that’s not happening.”

Surveillance ‘illegal’

His firm, Deighton Pierce Glynn, is representing three of Britain’s privacy organisations in a legal challenge against GCHQ, alleging that it has acted illegally by breaching the privacy of millions of British and EU citizens and broken article 8 of the EU human rights act.

Parliament didn’t anticipate the situation where all these tiny bits of data could be put together and find out things about people’s lives Daniel Carey

Big Brother Watch, the Open Rights Group and English PEN, together with German internet activist Constanze Kurz, have filed papers at the European Court of Human Rights bringing an action against the UK government. They initially tried to bring their case in the British courts, but the case was barred by the government, who said it would have to be heard at an investigatory powers tribunal, which are held in secret and from which there is no appeal.

“Mass surveillance systems create risks for everyone, and place extreme degrees of power in the hands of secret agencies,” said Jim Killock, executive director of Open Rights Group. “People living across the UK, Europe, the USA and beyond need the courts to protect their rights and start the process of re-establishing public trust.”

Hanging on the telephone

The court case was launched days after a particularly revealing senate judiciary hearing in the US, where the head of the NSA quietly admitted that a secret pilot programme monitoring the exact location of US citizens through their mobile phone data, was carried out back in 2010 to 2011.

In response, Christopher Calabrese, ACLU legislative counsel, said: “The NSA’s attempt to collect this data shows the need for stronger legislative oversight of the agency’s activities, but the fact is that federal, state, and local law enforcement are already regularly collecting cell phone location information without a warrant.”

It is just one disclosure out of many. But it demonstrates yet another huge overreach of the government’s access to some very fundamental information. Looking at previous academic studies, Arik Hesseldahl raised the question of what the NSA could have found out through its pilot, summarising: “In short, tracking your phone is a pretty good way to figure out who you know, where you’ve been and who you may have talked to.”

Even the most basic mobile phone handset constantly sends out signals about where we are and who we interact with, regardless of the many apps and sites we visit that do the same – something the Channel 4 News Data Baby Project is currently investigating.

‘There’s no guarantee that your phone is off’

Even turning off your phone isn’t enough in some cases, says Alex Plaskett, head of mobile security MWR. He said there are two relevant means of interception: “You’ve got the info that’s on the phone itself and then the data that is transmitted – so whatever data is sent from phone to the provider.”

“Mobile phone masts are always detecting your phone,” he told Channel 4 News. “You could turn it off, but there’s no guarantee that your phone is off. If the battery’s still in there, it could potentially power the radio part of the phone – for example if malicious software was installed first.”

There hasn’t been as much disclosure in the UK about what GCHQ holds on our mobile data. But on a broad level, we know that the security agency has been collecting and analysing all the electronic data going in and out of the UK through fibre-option cables. “We also know that GCHQ’s capacity for monitoring metadata – the tiny bits of data that we leave a long trail of, whenever we move around with a phone in our pockets – they have a much great capacity to monitor this data,” said Mr Carey. “That’s also of concern, and subject to a much lower degree of regulation.”

Ripa vs snoopers charter

UK surveillance of any kind is currently regulated by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (Ripa). But it was passed in 2000, when the nature of the way we communicate now was unimaginable. “Parliament didn’t anticipate the situation where all these tiny bits of data could be put together to find out things about people’s lives,” Mr Carey adds.

For example, Ripa requires ministerial warrants for surveillance of an identified individual. But monitoring “external” communications is much more lax, requiring a minister to sign a certificate every six months for ongoing surveillance.

And, Mr Carey argues, this applied to anything on the internet, as it all goes through external servers. “Purely because of the practical way that internet servers bounce things around the world, GCHQ can tap into that,” he said. “They’re seizing that data, storing it, sifting through it without any oversight.”

Before the Guardian published its first revelations about the NSA’s collection of phone records in June, UK parliament had been in fierce debate about a new communications data bill. Nicknamed the snooper’s charter, the bill proposed allowing government agencies like GCHQ access to all the data going in and out of the UK.

“In effect, the snoopers charter was an attempt to regularise what Theresa May knew what was already happening,” Mr Carey told Channel 4 News. “It’s a good illustration of why this case is needed and should be prioritised.”

The legal action will be funded through donations at www.privacynotprism.org.uk