Recession fears as economy shrinks

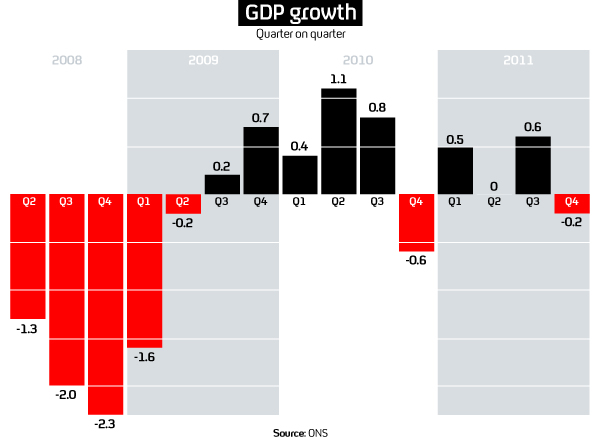

As official figures show that growth declined at the end of last year, Channel 4 News analyses what has happened to the British economy since the 2008-09 recession and what is in store.

The figures from the Office of National Statistics reveal that output dropped by 0.2 per cent in the last three months of 2011, a worse performance than expected. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), whose forecasts are used by the government, had predicted a 0.1 per cent fall.

The decline was driven by a 0.9 per cent fall in manufacturing, a 4.1 per cent drop in electricity and gas production, as the warm weather caused people to turn down their heating, and a 0.5 per cent fall in the construction sector. The services sector also ground to a halt.

If there is also negative growth in the first quarter of 2012, as many forecasters expect, Britain would be back in recession (defined as two quarters of declining gross domestic product).

During the 2008-09 recession, exacerbated by the banking crisis, the economy shrank by an alarming 7 per cent, with 15 consecutive months of declining output.

Since then, the recovery has been choppy: output rose slowly until the second quarter of 2010, when it recorded a respectable 1.1 per cent rise. After that there was growth. At the end of 2010, there was a decline of 0.6 per cent, but growth in the following three months showed that Britain had not slipped back into recession.

Shallow recession?

Another recession would obviously be worrying, because non-existent growth means higher unemployment and lower tax receipts. But the good news is that most forecasters do not believe the economy will nosedive as it did in 2008-09. Instead, they expect a shallow recession that leaves a dent in the road rather than a deep hole.

The OBR does not expect a recession in 2012. It predicted a 0.1 per cent decline in the last quarter of 2011 and a 0.1 per cent rise rise in the first quarter of 2012 – in other words a flat economy, with no growth, over six months. Across 2012, it expects modest growth of 0.7 per cent (a previous forecast predicted 2.5 per cent).

The Washington-based International Monetary Fund (IMF) believes the British economy will grow by 0.6 per cent, well below its previous forecast of 1.6 per cent, but faster than France and Germany and more impressive than the entire eurozone, where a 0.5 per cent fall in output is envisaged.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, in Paris, also expects the UK economy to grow in 2012, by 0.5 per cent. But it forecast a decline in the last quarter of 2011 and expects another fall in the first three months of 2012.

Pessimistic

Returning closer to home, forecasts are more pessimistic. The Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) and Capital Economics believe the economy will decline by 0.4 and 0.5 per cent respectively across 2012.

The Ernst and Young ITEM Club envisages growth of 0.25 per cent in 2012, but both it and the CEBR assume Britain’s recession is already likely to have begun, with negative growth at the end of last year and the beginning of 2012.

The ITEM Club expected a contraction of 0.2 per cent at the end of last year and forecasts a further drop of 0.15 per cent in the first three months of 2012. The CEBR predicted declines of 0.9 and 0.1 per cent.

The ITEM Club does not expect the economy to pick up until the summer, but it says Britain is not in line for a repeat of 2008-09.

The CEBR has revised down its growth forecast for 2012 from plus 0.7 per cent growth to minus 0.4 per cent, “with a risk of a more serious decline of 1.1 per cent if developments in the eurozone are especially negative”.

What happens next in the eurozone debt crisis is the big unknown. The dangers are so acute that IMF chief Christine Lagarde warned on Monday that if action was not taken, the world could find itself in a 1930s-style decline.

First, what is needed is a deal between the EU and indebted Greece’s creditors. EU and IMF help for Athens is contingent on an agreement with the holders of Greek bonds.

Greece

If this cannot be reached and Greece defaults on its debts, it could be forced out of the euro, with other heavily indebted southern European countries, like Italy, coming under pressure and the possible break-up of the single currency into northern and southern blocs.

There could also be problems if the euro survives, with spending cuts across the eurozone triggering a deep recession.

Of course, it may not end like this. The crisis in Greece could be resolved, with eurozone governments getting on top of their debts and forging a closer fiscal union.

But what we do know is that if the eurozone’s problems are not resolved, these forecasts would prove to be optimistic.