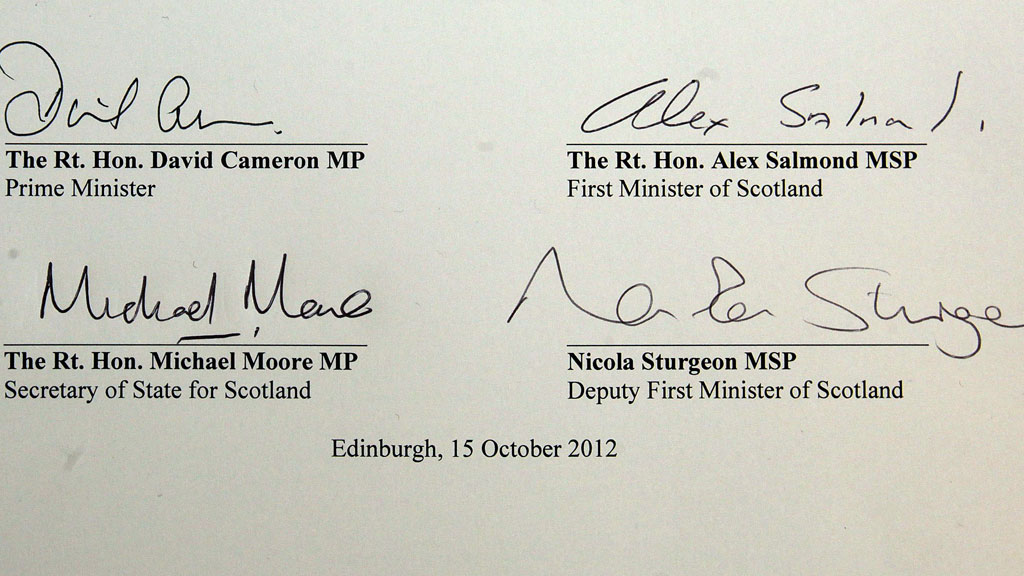

Sealing the deal on the independence vote

As David Cameron and Alex Salmond sign an agreement for a referendum on Scottish independence, we ask: which side benefited most in the negotiations, and are the Scots likely to go it alone?

The UK prime minister and Scotland’s first minister put pen to paper at Scottish government headquarters in Edinburgh, following months of negotiations.

Why is a referendum being held?

The pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP) won an overall majority in elections to the Scottish parliament last year, having campaigned for a referendum in the second half of its term in office.

The coalition government in London could not have ignored the result and has agreed to transfer the power to hold a referendum to the Scottish parliament.

When will the referendum be held?

The vote will take place in the autumn of 2014.

What will the question be?

Voters will be given a straight yes/no choice to a question phrased something like this: “Do you believe Scotland should be an independent country?”

At least that is what the SNP wants, but the Electoral Commission will also have its say, and Mr Salmond would be loath to ignore its advice.

What about ‘devo max’?

During negotiations between London and Edinburgh, there was talk of a third choice, asking people if they want more powers devolved from Westminster.

Aware from the polls that “devo max” has more support than independence in Scotland, and that more devolution could eventually lead to independence, the SNP was keen on the idea. But the coalition government rejected this option.

Who will vote?

For the first time, 16- and 17-year-olds will be able to vote in a UK election. This was on the SNP wish list, but previous elections show young people are less likely to make their way to the ballot box than older voters, so the party could find that it does not reap an electoral dividend.

Has the SNP got what it wanted?

The debate is raging over whether David Cameron has given too much ground to SNP leader Alex Salmond. The “devo max” option has been dropped, but Mr Salmond has got his way on the timing of the referendum (Mr Cameron wanted it to be held by the middle of 2013) and on votes for 16- and 17-year-olds.

Professor Robert Hazell, director of the Constitution Unit, said: “The UK government has won the first round, in particular through insisting on a single question. Of all the issues being negotiated, Salmond wanted most a second question on devo max.

“They had to be seen to offer Salmond something, and it was worth conceding on the timing of the referendum, and votes for 16- to17-year-olds, in order to ensure a single question.”

Lord (Michael) Forsyth, Scottish secretary in John Major’s cabinet, does not see it like this, branding Mr Cameron a Pontius Pilate figure.

He said: “Salmond has been able to get what he wants. If that’s called a negotiation, that’s stretching the language. It sounds like a walkover to me.

“What is going on here is the prime minister is Pontius Pilate. He is just saying, ‘Over to you, Alex.’ Once that order is passed, it’s a matter for Alex Salmond, so he’s going to dictate the terms.”

What about the Team GB effect?

The success of UK-wide athletes competing for the same team at the London Olympics and Paralympics this summer, with images of Scots Andy Murray and Sir Chris Hoy draped in the union flag, could have an effect in 2014.

The pro-union campaign, Better Together, can point to a joint endeavour that reaped dividends for the Scots and the other home nations.

But the Commonwealth Games will be held in Glasgow from 23 July to 3 August, 2014 – with the home nations competing separately.

Assuming the performance of Scottish athletes is boosted by competing on home terrain, and the Games are successfully staged, the SNP and the yes campaign could use the event to encourage Scottish pride – shortly before the referendum is held.

If the Scots reject independence, is that the end of the matter?

Mr Salmond and his party would suffer a grievous blow if independence is overwhelmingly rejected, and the pro-union camp would argue that the Scots have spoken and the issue should now be put to bed.

But if independence is narrowly rejected, Mr Salmond could argue that Scotland’s constitutional relationship with England should be revisited at a future date.

Prof Hazell said: “The UK government had hoped that the referendum might decide the issue of Scottish independence once and for all. But these issues cannot be resolved for all time. The issue of how much independence and autonomy Scotland should have will always be with us, just like the never ending debate about Quebec in Canada, or Catalonia and the Basque country in Spain.”

What do the polls show?

Peter Kellner, president of YouGov, could not be more blunt, describing the SNP’s quest for independence as “mission impossible” and saying that “all YouGov’s evidence from the past four years is that independence is a minority passion north of the border”.

Mr Kellner believes Mr Salmond’s proposed question – “Do you believe Scotland should be an independent country?” – is loaded, but argues that this will not “make any difference to the outcome” because electors will have had months to make up their minds and will either vote for or against independence, whatever the wording.

Nor can Mr Salmond rely on the under-18s for support. “Even if all 16 and 17-year-olds who are entitled to vote are added to the register, this will add 3-4 per cent to the electorate.

“All the evidence is that the younger the elector, the less likely he/she is to vote. And those who do vote do so in roughly the same shares as their parents.

“Changing the voting age might make no difference whatsoever, or even reduce the yes share fractionally. Again, Cameron has done the unionist cause no real harm by conceding the point.”

Mr Kellner argues that Mr Salmond “will have to defy history” to win. As daunting as that sounds, it is unlikely to worry the SNP leader.

Although the odds are obviously against a break-up of the UK, has he not already defied history by ensuring that a referendum on independence is held for the first time?

He was able to do this by winning an overall majority at Holyrood – a scenario that looked implausible when Tony Blair’s government established the Scottish parliament.

Mission impossible for a man considered to be Scotland’s most formidable politician? More like mission unlikely.