Family misfortunes – the harsh reality of immigrant life

Jamal Osman

Africa Correspondent

Jamal Osman

Africa Correspondent

Being an immigrant is like being the youngest child, writes Jamal Osman. You might be the weakest member in your newly adopted family, but you are often blamed for anything that goes wrong.

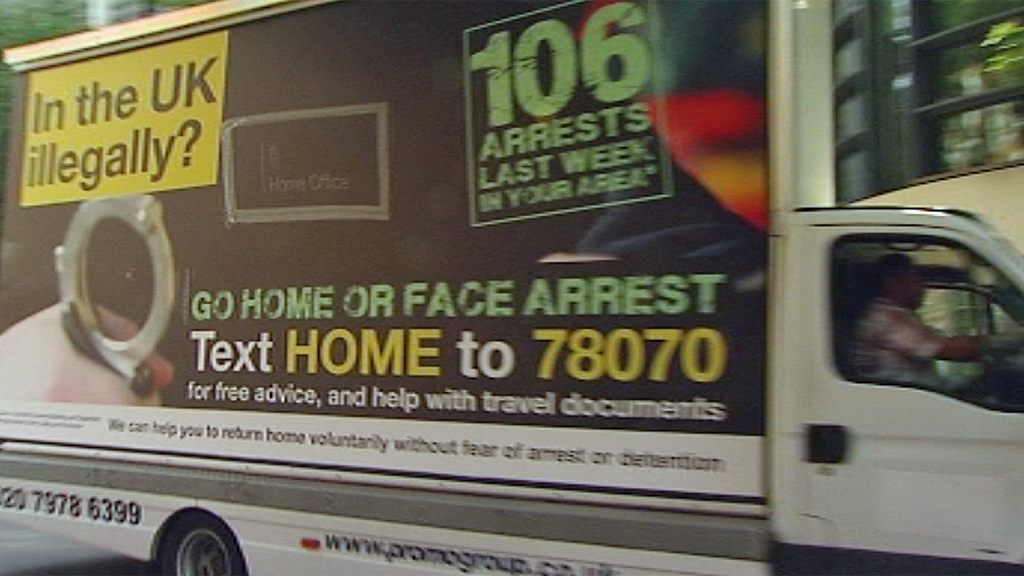

Sometimes I wonder if Brits realise how it feels to be an immigrant in this country. I am an immigrant here – and it’s tough to be living in a place where there is constant talk of “migrants go home”. We are accused of taking British jobs from British people, of claiming benefits and of exploiting the national health system.

Elections campaigns are not the best of times for us because we become one of the main talking points. And it’s already started, although the next general election is still 18 months away.

To get more votes, many politicians focus on the negative aspects of immigration, and foreigners become the focus – people who are some of the most vulnerable members in the society.

Despite living through terrible experiences – remember, many immigrants are fleeing unimaginable violence and hunger – there appears to be little sympathy for them here. In my experience there is little desire to understand their desperation, and to understand why they risk their lives on terrible journeys to come here.

Don’t get me wrong. I enjoy living and working in the UK. Britain is now my home. But I get hurt and upset by the attitude of many here towards me and other immigrants.

Blamed for everything

In theory, once you are given the permission to stay in this country, you are accepted. But in reality you are made to feel like it was a mistake.

Being an immigrant is in many ways like being the youngest child of a family. You might be the weakest member in your newly adopted family, but you are blamed for everything that goes wrong.

Your foster parents (the government) keep on telling the world about their ill feelings towards you and how they need to be very strict on you. It is as if you slipped through the back door without asking anyone. You are simply an unwelcome intruder.

In theory, once you are given the permission to stay in this country, you are accepted. But in reality you are made to feel like it was a mistake.

It is your problem if your biological parents (your home nation) were violent, poor or irresponsible.

Everyday you see your foster parents and neighbours (politicians) blaming each other for the fact that you are in the country. There is a talk of how important it is to control your movements.

Your foster parents and the public agree that you don’t deserve to be a valued member of the family. Instead, you should be waiting for the leftovers, until everyone else has eaten (“British jobs for British people”). Even when you settle for the leftovers (jobs that Brits don’t want to do), you still get blamed. You just cannot win.

Like you’re not there

Every evening when the family sits down for a dinner, your existence is an important part of the dinner-table discussion (regular debates about migrants). Even though you are close by, they talk about you and how to get rid off you. You are treated as if you are not there, as if you are not hearing anything and have no feelings.

We, migrants, watch, listen and read hostile media coverage against us all the time. And it feels terrible.

If someone isn’t feeling well and can’t get an appointment with the local doctor, we are blamed. It doesn’t matter whether you use the health service or not. You might even be one of those working in the NHS. Either way, your presence is an issue.

If something goes wrong, it’s obvious who did it. Some sections of the media portray migrants as criminals.

If something goes wrong in the house, it’s obvious who did it. Some sections of the media portray migrants as criminals.

Often you are criticised for not making enough effort to be part of the family. But when you try to fit in and, like Brits, you start a conversation about the weather, you are told to “go home if you don’t like the weather in this country”.

The Brits may think this as “an important debate to have” but for migrants it’s plain bullying. If this was happening to a child, the social services would have stepped in.

In this, the United Nations and human rights groups should be acting as social services – but they rarely do.

We are children who have somewhere to sleep, something to eat and are generally better off in our new homes. But with all the negative comments, there will inevitably be psychological damage.

Many of us feel demoralised and wished the Brits showed more compassion towards us and considered the effect of blaming us for all this country’s ills.

I have made a new life in the UK with my family, but it’s hard tno to feel demoralised sometimes – and I wish Brits would show more compassion towards us and consider the effect of blaming us for all this country’s ills.

After all, we are fellow human beings who have come here to have a better life.

Jamal Osman is a reporter for Channel 4 News