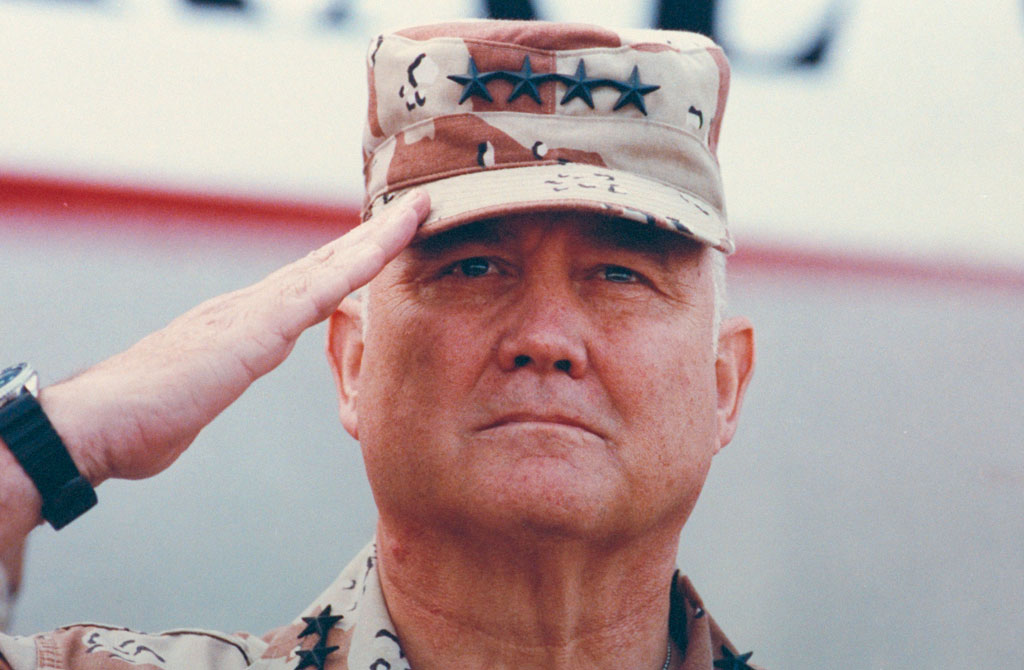

US General Norman Schwarzkopf dies aged 78

Retired US General Norman Schwarzkopf, who led troops in the 1991 Gulf war, has died aged 78 in Tampa, Florida, the American military confirms.

The highly decorated four-star general died on Thursday afternoon at his home in Tampa, Florida.

The cause of death was not immediately known.

Schwarzkopf, a burly Vietnam War veteran known to his troops as Stormin’ Norman, commanded more than 540,000 U.S. troops and 200,000 allied forces in a six-week war that routed Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s army from Kuwait in 1991, capping his 34-year military career.

Some experts hailed Schwarzkopf’s plan to trick and outflank Hussein’s forces with a sweeping armored movement as one of the great accomplishments in military history. The maneuver ended the ground war in only 100 hours.

In a statement released by the White House, President Barack Obama called Schwarzkopf “an American original” whose “legacy will endure in a nation that is more secure because of his patriotic service.”

Former U.S. President George H.W. Bush, who built the international coalition against Iraq after the invasion of Kuwait, said he and his wife “mourn the loss of a true American patriot and one of the great military leaders of his generation,” according to a statement released by his spokesman.

Bush has been hospitalized in Houston since late November.

Physical presence

Schwarzkopf was a familiar sight on international television during the war, clad in camouflage fatigues and a cap. He conducted fast-paced briefings and reviewed his troops with a purposeful stride and a physical presence of the sort that clears bar rooms.

Little known before Iraqi forces invaded neighboring Kuwait, Schwarzkopf made a splash with quotable comments. At one briefing he addressed Saddam’s military reputation.

“As far as Saddam Hussein being a great military strategist,” he said, “he is neither a strategist, nor is he schooled in the operational arts, nor is he a tactician, nor is he a general, nor is he a soldier. Other than that, he’s a great military man, I want you to know that.”

Schwarzkopf returned from the war a hero and there was talk of him running for public office. Instead, he wrote an autobiography – “It Doesn’t Take a Hero” – and served as a military analyst.

He also acted as a spokesman for the fight against prostate cancer, with which he was diagnosed in 1993.

Son of police chief

Schwarzkopf was born in 1934, in Trenton, New Jersey, the son of Colonel H. Norman Schwarzkopf Sr., the head of the New Jersey State Police.

At the time, the older Schwarzkopf was leading the investigation of the kidnapping and murder of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s infant son, one of the most infamous crimes of the 20th century.

The younger Schwarzkopf graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1956. He earned a masters degree in guided-missile engineering from the University of Southern California and later taught engineering at West Point.

Schwarzkopf saw combat twice – in Vietnam and Grenada – in a career that included command of units from platoon to theater size, training as a paratrooper and stints at Army staff colleges.

He led his men in firefights in two tours of Vietnam and commanded all U.S. ground forces in the 1983 Grenada invasion. His chestful of medals included three Silver and three Bronze Stars for valour and two Purple Hearts for Vietnam wounds.

Tough soldier

In Vietnam, he won a reputation as an officer who would put his life on the line to protect his troops. In one particularly deadly fight on the Batangan Peninsula, Schwarzkopf led his men through a minefield, in part by having the mines marked with shaving cream.

In 1988, Schwarzkopf was put in charge of the U.S. Central Command in Tampa, with responsibility for the Horn of Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. In that role, he prepared a plan to protect the Gulf’s oil fields from a hypothetical invasion by Iraq. Within months, the plan was in use.

A soldier’s soldier in an era of polished, politically conscious military technocrats, Schwarzkopf’s mouth sometimes got him in trouble. In one interview, he said he had recommended to Bush that allied forces destroy Iraq’s military instead of stopping the war after a clear victory.

Schwarzkopf later apologized after both Bush and Defense Secretary Dick Cheney fired back that there was no contradiction among military leaders to Bush’s decision to leave some of Saddam’s military intact.

After retirement, Schwarzkopf spoke his mind on military matters.

Questioned Iraq’s nuclear weapons

In 2003, when the United States was on the verge of invading Iraq under President George W. Bush, Schwarzkopf said he was unsure whether there was sufficient evidence that Iraq had nuclear weapons.

He also criticized Donald Rumsfeld, the secretary of defense at the time, telling The Washington Post that during war-time television appearances “he almost sometimes seems to be enjoying it.”

Schwarzkopf and his wife, Brenda, who he married in 1968, had two daughters and one son.

In a statement, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta praised Schwarzkopf as “one of the great military giants of the 20th century.”

General Martin Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said he “embodied the warrior spirit,” and called the victory over Hussein’s forces the hallmark of his career.