Ye Shiwen: why is she being accused of doping?

As Chinese gold medal-winning swimmer Ye Shiwen faces accusations that she used banned drugs in the Olympics, Channel 4 News looks at the evidence.

John Leonard, a top American swimming coach and executive director of the World Swimming Coaches Association, could not have been any blunter.

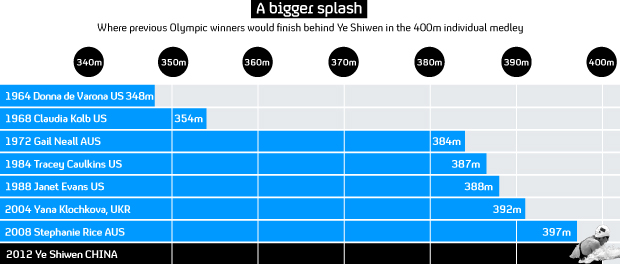

The performance of 16-year-old Ye Shiwen, who won gold in the 400m individual medley on Saturday, was “disturbing”.

He told the Guardian: “She looks like superwoman. Any time someone has looked like superwoman in the history of our sport they have later been found guilty of doping.”

The swimmer, who has been tested for banned substances, has denied using drugs to enhance her performance in the pool. “My results come from hard work and training and I would never use any banned drugs. The Chinese people have clean hands,” she said.

‘Destructive’

Others have also leapt to Ye’s defence. Duncan Goodhew, who won a gold for Britain in breaststroke at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, told ITV Daybreak: “I think it is very destructive and very irresponsible of anybody to accuse people until they are proven guilty.”

I think it is very destructive and very irresponsible of anybody to accuse people until they are proven guilty. Duncan Goodhew, Olympic swimmer

International Olympic Committee (IOC) medical commission chairman, Arne Ljungqvist, said he had no reason “other than to applaud what has happened, until I have further facts, if so”.

So why the suspicion? In echoes of the cold war, Ye’s gold was at the expense of the American Elizabeth Beisel, who won silver. But there is more to it than US-Chinese rivalry. In the race, Ye shaved five seconds off her personal best and set a new world record.

Faster

There has also been comment about the fact that in the last 50m, she swam faster than the American champion Ryan Lochte in the men’s individual medley final.

But – and it is a big but – Ye was 23 seconds slower overall and 14 seconds slower than the last-placed swimmer in the men’s final. In other words, she was slower than all the men over 400m.

Over the last 50m, she was slower than four of the eight men. In the last 100m, she was slower than five of them.

John Leonard explained his misgivings. “The one thing I will say is that history in our sport will tell you that every time we see something, and I will put quotation marks around this, ‘unbelievable’, history shows us that it turns out later on there was doping involved,” he said.

“That last 100m was reminiscent of some old East German swimmers, for people who have been around a while. It was reminiscent of 400m individual medley by a young Irish woman in Atlanta.”

Mr Leonard was referring to Irish swimmer Michelle Smith, who was banned for four years in 1998, two years after the Atlanta Olympics, after testing positive for androstenedione.

Previous

China has previous here, too. During the 1990s, 40 Chinese swimmers tested positive for banned substances, and seven before the Beijing Games in 2008.

At the 1994 World Championships in Rome, China won 12 of the 16 women’s titles. Weeks later, seven Chinese swimmers tested positive for banned drugs at the Asian Games in Hiroshima.

In Perth in 1998, four Chinese swimmers were sent home after failing drug tests. A week earlier, a fellow teammate and her coach had been stopped at Sydney Airport trying to smuggle human growth hormone.

A Chinese crackdown followed, with 27 athletes pulled from the Olympic team before the 2000 Games in Sydney. China’s swimmers managed one gold medal at the 2004 Athens Olympics, but nothing at the 2005 and 2007 World Championships.

There was an improvement at the Beijing Olympics in 2008, but last month the 16-year-old world champion in the 4x100m medley, Li Zhesi, tested positive for the blood-boosting drug EPO.

Testing

What must not be forgotten is that athletes at the London Games have faced, and are facing, the toughest anti-doping crackdown that has ever been carried out, with more than 6,000 blood and urine tests.

But the IOC’s Arne Ljungqvist has pointed out that the number of tests is not the only criterion: at these Games, the innovation is testing based on intelligence.

This means individual athletes, or groups of athletes, will be targeted – and anyone finishing in the top four of any event is automatically tested.

Strychnine

The use of performance-enhancing drugs at the Olympics can be traced back to 1904, when marathon winner Thomas Hicks used strychnine and brandy to help him race.

In the following decades, drug use became more widespread, and in 1967, the IOC took action and banned it.

This did not stop East German female athletes, particularly swimmers, from using anabolic steroids in the 1970s and 1980s – and winning an impressive crop of gold medals.

Nothing was proved at the time, but after the fall of the Berlin Wall, documents were discovered which showed the athletes had been part of a state-sponsored programme to improve performance at international sporting competitions.

Disqualified

The World Anti-Doping Agency was formed in 1999, but in the 2000 summer Olympics and 2002 winter Olympics, several medal winners in weightlifting and cross-country skiing were disqualified after failing drug tests.

At the 2008 Beijing Olympics, six athletes fell foul of the IOC’s drug-testing regime. Before the Games, several others were banned from competing by their own countries.

That may not be the end of the matter. Other positive tests are possible because samples are kept for eight years. This is just as well: there are a number of drugs that cannot be detected at the moment.