Ariel Sharon: soldier, statesman or war criminal?

Loathed by Palestinians and a divisive figure in Israel, Ariel Sharon played a part in six decades of conflict in the Middle East.

Sharon was born to Russian immigrant parents in 1928 in a farming community north of Tel Aviv in what was then the British Mandate for Palestine.

At 14, six years before the creation of the state of Israel, Sharon joined the Haganah, the Jewish paramilitary organisation that would later become the Israeli Defence Force.

He commanded an infantry brigade in the 1948 war between the new Jewish state and its Arab enemies.

Sharon had a reputation for insubordination but his successful use of hit-and-run tactics against Arab forces earned him rapid promotion.

In 1953 he helped form Unit 101, a unit that carried out reprisals for the slaying of an Israeli woman and her two children. His troops blew up more than 40 houses in Qibya, a West Bank village then ruled by Jordan, slaughtering 69 Arabs. Sharon later said he thought the houses were empty.

After Israel’s 1956 invasion of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, Sharon was rebuked for engaging his troops in what commanders regarded as an unnecessary battle with Egyptian forces. Some 38 Israeli soldiers died along with more than 200 Egyptians.

But Sharon, by now a major general, was praised for his command of an armoured division during the 1967 Middle East War, in which Israel captured and occupied the West Bank, Gaza Strip and Sinai Peninsula.

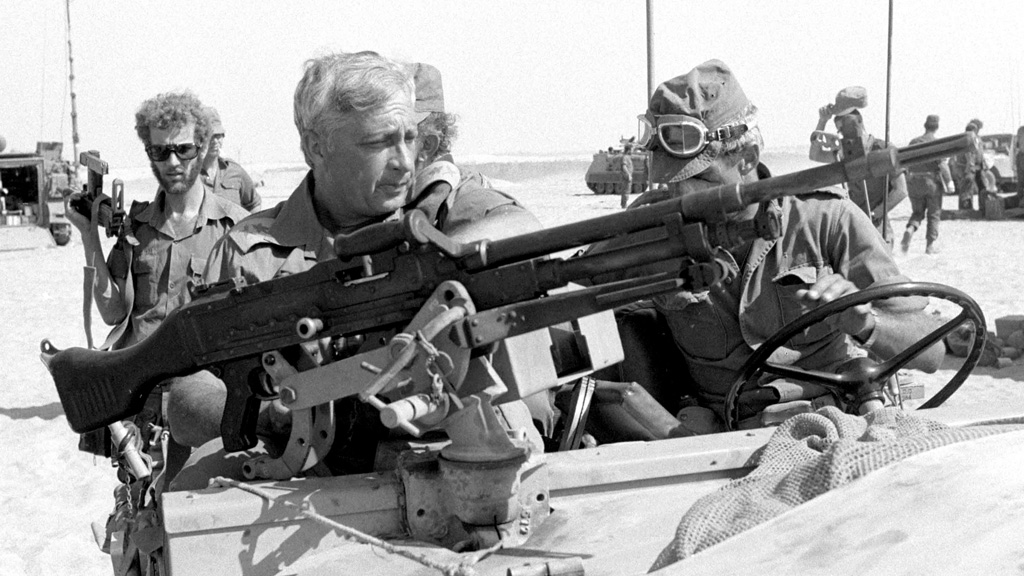

In the 1973 Yom Kippur war, he was called back into active service and commanded 27,000 Israelis in a decisive drive across the Suez Canal into Egypt.

The complex manouevre helped turn the tide of the war and Sharon recalled it as his finest hour in uniform.

As defence minister, Sharon engineered the country’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, a conflict that would spark the most controversial episode of his life.

In September 1982, Israeli troops had surrounded two Palestinian refugee camps, Sabra and Shatila when allied forces from the Lebanese Christian Phalange militia group entered and slaughtered hundreds of unarmed people.

An Israeli commission rejected Sharon’s contention that he knew nothing about the massacre and found him to bear “personal responsibility”, costing him his job as Defence Minister.

The commission advised that he should not hold public office again, but Sharon rejected the findings and pledged to remain in politics.

In 2001 lawyers representing relatives of Sabra and Shatila victims attempted to have Sharon tried for war crimes, but Belgian judges ruled the case was inadmissible.

As a cabinet minister in the 1980s and 90s, Sharon led a push to build dozens of Jewish settlements in the West Bank and Gaza, despite international protests.

After being elected prime minister in a landslide election in 2001, he oversaw the Israeli assault on the Palestinian refugee camp in the West Bank town of Jenin, seen by some as a massacre of civilians and a war crime.

A United Nations investigation rejected claims that hundreds of Palestinian civilians were killed, saying the overall number of Palestinians killed was 52 – around half of whom may have been civilians.

He was re-elected to a second term in 2003 and began the construction of Israel’s separation barrier.

Despite his reputation as a hard-liner, Sharon referred to Israel’s control of the West Bank and Gaza as an “occupation” – and conceded that an independent Palestinian state was inevitable.

He oversaw the end of Israel’s 38-year occupation of Gaza in August/September 2005 and the withdrawal from four settlements in the northern West Bank in the face of enormous domestic hostility.