Should Boots’ parent company pay more corporation tax?

Siobhan Kennedy

Washington Correspondent

Siobhan Kennedy

Washington Correspondent

As Boots’ parent company, Boots Alliance, posts increased profits, Channel 4 News Business Correspondent Siobhan Kennedy asks whether it is time the UK taxman took more of a share?

Private equity chiefs. Masters of the Universe. Remember them? Back in 2007 they were hardly out of the headlines.

There was a camel famously parked outside the home of one of the UK bosses and a group of red-faced financiers were hauled in front of the Treasury Select Committee to explain why they paid less tax than their cleaners.

But then the credit crunch hit and the private equity men were probably the only ones who drew a sigh of relief. It took them out of the spotlight as quickly as they had fallen into it. And that’s where they’ve stayed, largely, ever since.

But if you ever needed a reminder of the way private equity works, and perhaps why the rules still require much-needed updating, just take a look at Alliance Boots results.

A quick recap on why Boots matters. The acquisition of the much-loved high street chain was the last big hurrah of the banking boom. It came at the very height – no, the apex – of the market being financed, as it was, by £9bn of debt.

The banks were tripping over themselves to lend to Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, the American private equity firm that bought the group. In fact such was the hype around Boots that the banks, chief among them Barclays as I recall – were even desperate to get a slug of the equity, something typically reserved just for the private equity firms themselves.

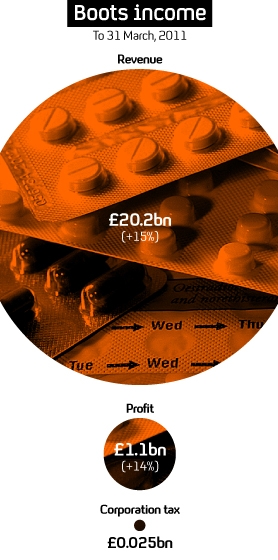

Fast forward to today and it’s hard to say that private equity ownership has been a bad thing. Alliance Boots’ trading profit has risen 14 per cent since 2007 to just over £1bn in 2010/11 on sales that have swollen to £23.3bn.

It’s expanded internationally and domestically through acquisition and in the UK its margins have increased to more than 10 per cent. We all still love Boots and we shop there every weekend don’t we?

Taxman loses out?

But Boots’ success has been at the taxman’s expense. As a major player in the FTSE 100, the group used to contribute anywhere between £100m and £150m a year in corporation tax. But because of the way the tax system works, the company’s contribution has fallen off a cliff since the Americans moved in and took the reins.

That’s because under UK rules, KKR can offset the amount of interest it pays on its debt against UK tax. Ergo, the more interest you pay, the less tax goes to the exchequer. With debt of about £7.8bn (it’s been reduced since the original deal), it’s no wonder Alliance Boots only paid £25 million in tax in the past financial year.

To be fair, all companies – not just private equity – can do the same. But the essence of the Treasury’s rules are meant to apply to firms where loans are being issued to start and crucially to grow businesses. It’s hard to see how KKR’s purchase of Alliance Boots fits that bill.

Boots was hardly a small company, it was already very profitable. KKR, like all private equity companies, simply chose to buy the group using mostly debt. All private equity firms do the same. From New Look to Café Rouge to Manchester United there are mountains of debt up and down the country. What makes this purchase different is the sheer size of that debt, which is so huge it dramatically reduces the company’s profits and hence its tax bill.

Alliance Boots would argue – and indeed its boss Stefano Pessina did today – that it’s not breaking any rules, that it’s paying the amount of tax it’s required to and that what’s left of the profit isn’t being squirreled away in Swiss bank accounts (although that’s a moot point some would argue given the company is now headquartered in the tax-haven canton of Zug in Switzerland). And all that is true.

Tax loophole

But there’s something about a company as big and as profitable as Alliance Boots paying less tax than a small independent high street pharmacist that some would say doesn’t seem fair. Isn’t it time for the Treasury Select Committee to dust off its private equity files and get the issue back on the agenda?

And for George Osborne – busy looking for ways to generate more tax income amid painfully slow economic growth – to cast his glance over to Mayfair and crack down on one very obvious loophole that’s plain for all to see.

Australia, for example, has ruled that interest isn’t tax deductable beyond a certain level of debt. That seems a logical and simple way of addressing the problem. Why can’t the Treasury do something similar here?