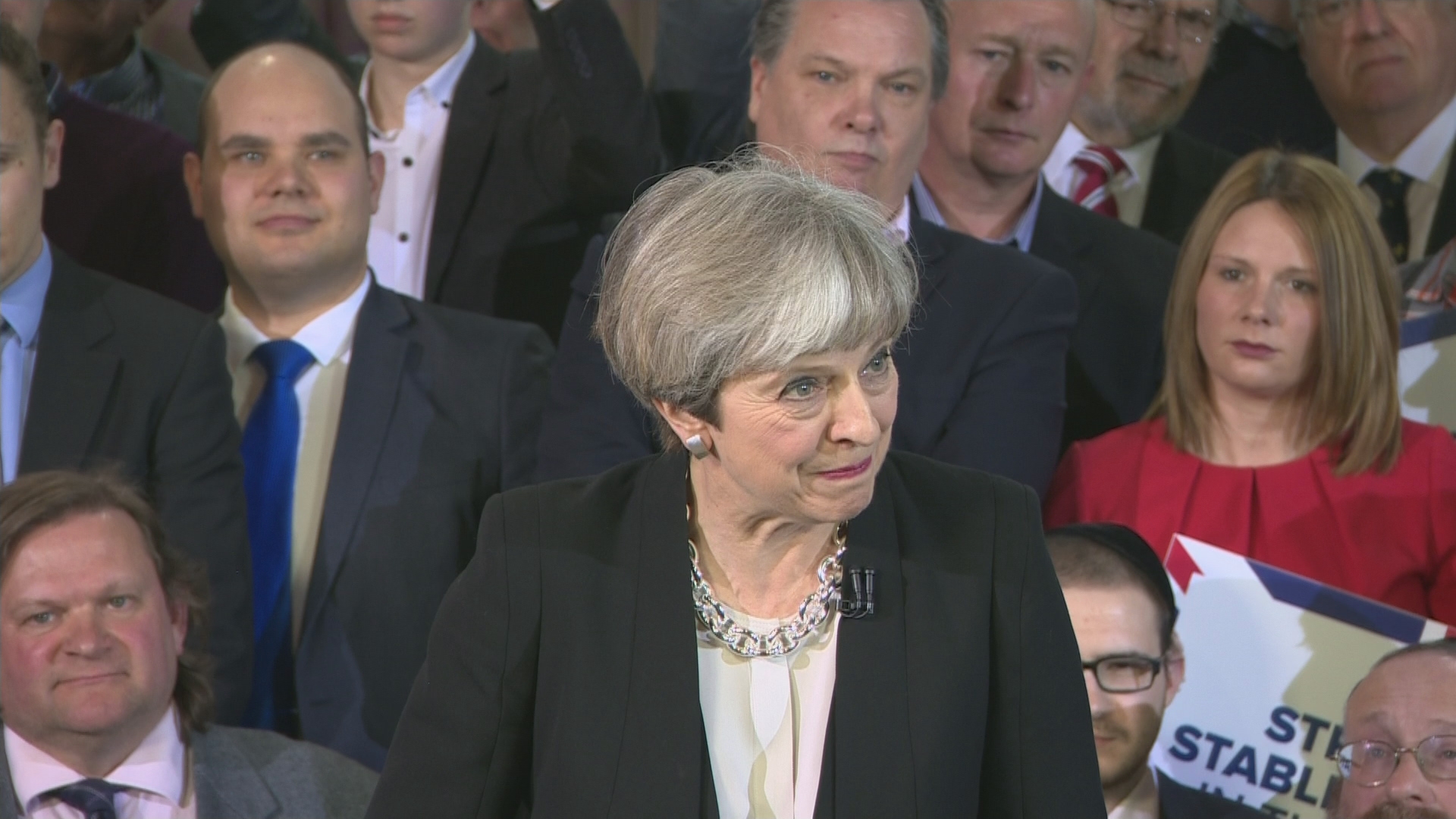

A portrait of a young Theresa May: the ‘enigmatic’ student who wanted to roll back socialism

10m

10m“Enigmatic” is the word Alicia Collinson uses to describe Theresa May back when she first met her, 43 years ago.

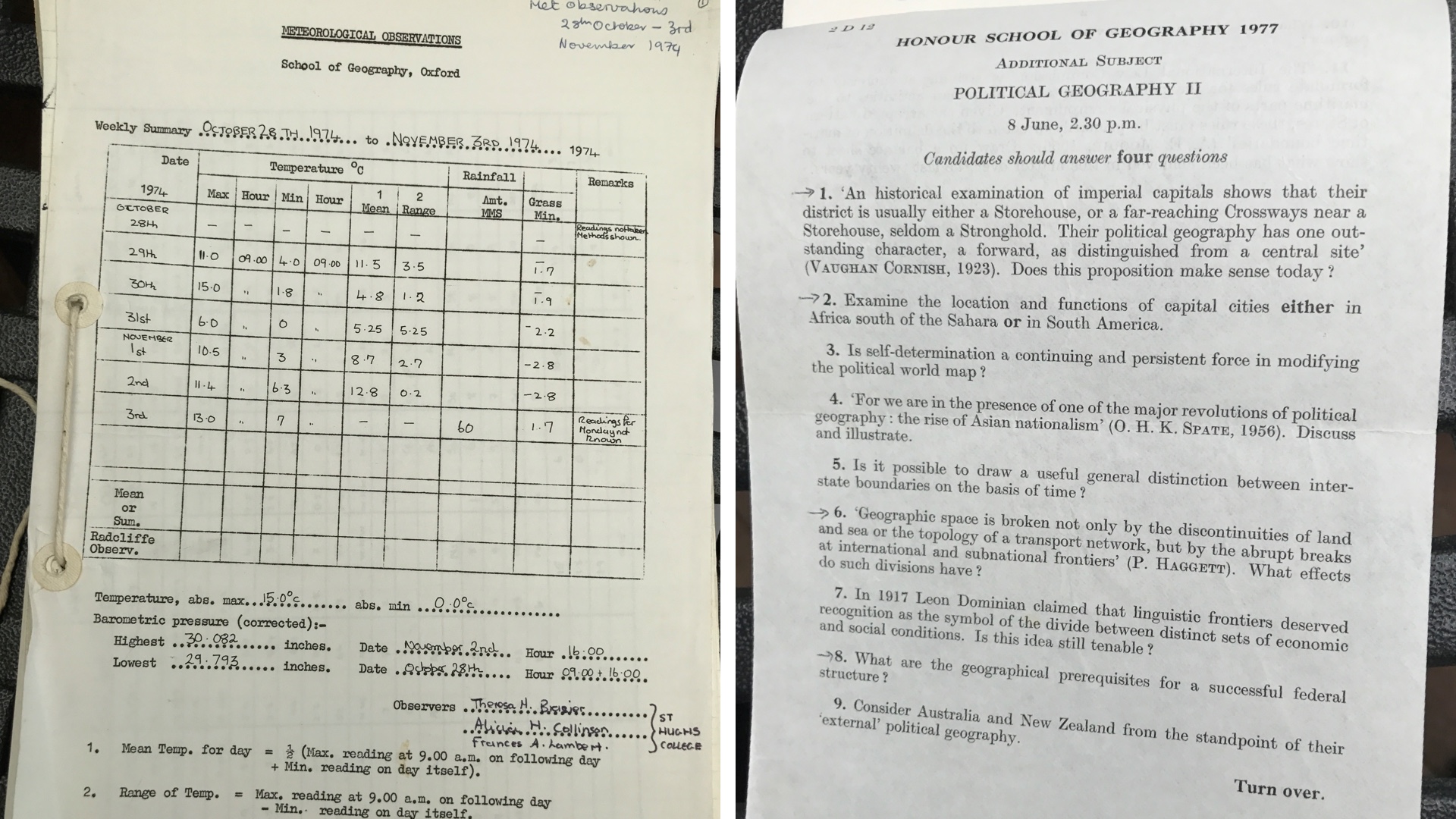

They were tutorial partners at Oxford, arriving on the day of the second 1974 general election. Theresa May was 17, already a member of the Conservative Party. Alicia Collinson, now a barrister, married to Damian Green, a fellow Oxford undergraduate, says Theresa May made fellow undergraduates laugh at the jokey debating society they all joined. Alicia sketched the young Theresa Brasier, very much in charge with punt pole in hand. In front of her the man who would become her husband, Philip May, popping a champagne cork to mark the end of Finals.

Alicia Collinson remembers Theresa May telling her in their first term at Oxford that she wanted to become Prime Minister. Theresa May has said she doesn’t recall that.

On a visit to the Oxfordshire church where Theresa May’s father was the vicar for the last 11 years of his life, we met a parishioner who recalls her father and his very focused only child. Olive Spink says that even when Theresa May was at the local school she told fellow pupils that she wanted to be Prime Minister.

So no question about early ambition, but what was all it all for?

Theresa May’s late mother was a Conservative. Her father, Rev Hubert Brasier, was careful to avoid public political attachments but seems to have shared those views. You get the impression of an only child not afraid of her own company whose formativie social embrace is the Conservative Party. Theresa May’s campaign team might have minimised the font on the Party name in this election but it looms large in her life. She stuffed envelopes as a teenager and was a member before she arrived at Oxford, on the day of the October 1974 General Election.

Alicia Collinson remembers the key motivation for her Geography tutorial partner being to “roll back socialism … there was rather a lot of it about back then,” she says. Some Treasury and business voices, irritated by what they see as interventionist tendencies in No. 10 will roll their eyes at that.

One source close to Theresa May has lamented that being anti-state has become a badge of conservatism and it has all got out of hand. Standing side by side with her Chancellor today, Theresa May dismissed talk of a fall-out with Philip Hammond but notably failed to promise he would keep his job the other side of the general election. If he doesn’t, it could be a signal that she and her joint chiefs of staff are going to try to push an agenda for greater state interventions in the market. Labour points out that they haven’t exactly been revolutionaries in her first 10 months in office.

Nick Clegg, who came to respect her in some ways when they worked alongside each other in the Coalition, says he can’t recognise her from the Tory sloganising. He claims that Mrs May lacked the flair or self-confidence to come to a judgement and instead “laboriously” waded through papers, drawing out a decision or compromise that was clear from the start to others.

That’s probably the sort of breezily self-confident comment that Theresa May would loath. Around Westminster, before this Parliament was dissolved, you regularly heard Tory ministers and backbenchers worry that the Prime Minister’s political agenda was sometimes being shaped in opposition to the David Cameron regime which she felt had condescended to her.

So will she paint in bold colours if she gets back in? Or will the whole thing be a bit like an innings by her childhood hero, Geoffrey Boycott, inching forwards in sleep-inducing play?

Paul Goodman of ConHome says he thinks he’s found a pattern you can expect: a low attritional innings with occasional lashing out for a six. We could end up half a dozen surprising measures which subvert the usual political genres but don’t add up to a coherent philosophy.