Amid Britain's own storm damage, spare a thought for a faraway island

It came without warning in the midst of the dry season. On the very night Britain was suffering its own storms, power cuts and floods.

Saint Vincent, a small Caribbean island state, suffered one of the most violent storms in living memory. In the heart of the dry season, months away from the rainy weeks from June to September, the deluge came without warning of any kind.

Between 9pm on Christmas eve and 1am on Christmas day, 11 inches of rainfall were recorded. The consequences in the hilly, volcanic, forested island were catastrophic.

Whole hillsides, weakened in the hurricane of 2011, this time gave way altogether. It is estimated that the country has lost 10 per cent of its forested land, and forests carpet most of the landmass here.

Staying on a neighbouring, though unaffected, island the other day, by chance I met the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) Minister Alan Duncan who, coincidentally, was staying on the other side of the island I was on.

We agreed to go together to St Vincent to see the damage for ourselves and meet with the island’s Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves.

He told us 13 of his 109,000 people had died, dozens had been injured. Three hundred families are still homeless; 28 bridges have been destroyed, many roads have been washed away, and many homes damaged. Some 6,000 people will spend their eighth night without running water.

The tragedy deepens as Mr Gonsalves talks of the development projects which keep having to be put on hold whilst resources are moved to cope with each emergency. He is in no doubt that St Vincent is in the eye of the storm that is climate change.

It may be difficult for politicians to announce funding for other people’s flood disasters when the UK is itself suffering. Yet the effect of the storm crisis here is hugely amplified by lack of infrastructure. The equivalent death toll in Britain’s population would have been 6,000 people.

The prime minister pleaded with Alan Duncan for immediate help that might tide them over until the Caribbean Development Bank (to which the UK contributes), the World Bank, and the EU can respond.

So Mr Duncan has come up with £100,000 for immediate aid and promises of further once specific needs are evaluated and costed.

The celebrity island of Mustique (part of St Vincent’s sovereign territory) has raised £200,000 inside a week, and sent blankets mattresses, clothing, and more.

What is really needed here are immediate technicians – forestry experts, bridge builders, people who understand water courses.

So that a fast evaluation can be made as to what is needed and how far St Vincent can be protected against another such deluge.

Norway, Germany, Canada, all have such experts as do we. The prime minister tells me 50 of them would make a massive immediate difference to sorting out this crisis.

In the meantime as we drove around where we could with the minister for public works, a gifted man named Julian Francis, we could not reach the worst affected areas. Along our way, we could see endless groups of local people using their own simple implements to try to begin to assault the damage.

Finally, spare a thought for St Lucia, an island I could not get to today.

They too were hit by the same storm. These are two former British colonies, now members of the Commonwealth.

As we in Britain battle our own storm damage perhaps it’s worth considering the value of being able to help others even less fortunate than ourselves.

If DFID is to mean anything to us, it must prove our agent in helping to resolve this far away crisis.

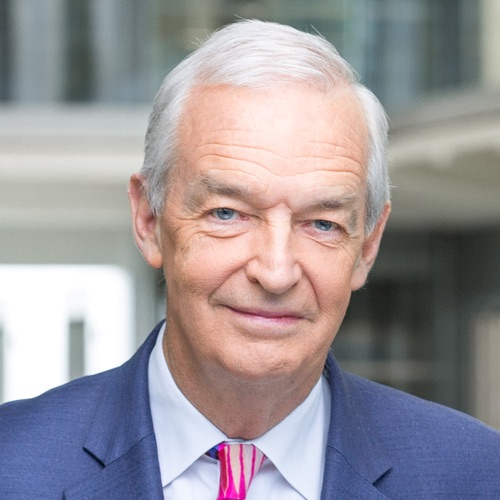

Follow @jonsnow on Twitter