Hugo Chavez, the gringo and the rest of us

When I first started working in Central and Latin America in the early 1980s, the United States was still emerging from a period of widespread interference in the government of countries in the region.

The 1954 CIA coup which deposed President Arbenz in Guatemala set a trend which continued well into the 1970s, with the similar CIA-engineered coup that deposed President Allende. Allende was replaced by the US-friendly dictator Augusto Pinochet. To read, or indeed to live, the history of the times was to experience events that fiction could never match.

Standing in San Salvador outside the tattered cathedral in the aftermath of the funeral of Archbishop Oscar Romero, I remember wondering what role, or knowledge, the US might have had in his assassination.

US military advisers were covertly and overtly very present in El Salvador. They believed that a pro-Castro coup might seize power and work against US interests in the region, and that the “liberation theologians” like Romero were on the “wrong side”.

But in truth, the largely peasant movement raging in El Salvador at the time was one for liberation from the power of the oligarchs and the death squads they sponsored. Many were the mornings in the Hotel Camino Real when we would awaken to see the corpses of half a dozen peasants laid out in the car park below to impress our small band of journalists.

Wherever you went in those days – Nicaragua, Honduras, Colombia – the people would talk darkly of the “gringo” and his intentions in their region. Washington was actively feared by those who sought change.

Hugo Chavez was one of those Latin American leaders who determined to end US interference in the governance of their countries. But I would argue that above all, he was the unlikely beneficiary of Osama bin Laden’s attack on America on 9/11. Within months, America’s attention turned sharply east to Afghanistan and later to Iraq in pursuit of a new and more deadly foe.

Many Venezuelans believe the CIA would have removed Chavez were it not for that vast shift in America’s military might. While several US-backed attempts were made to dislodge Chavez, they had none of the commitment or the success that had removed Arbenz, Allende and so many others.

Hence Chavez was free to introduce his own revolution in which his original devotion to the gun embraced the ballot box. Above all, he had the wealth of the world’s largest untapped reserves of oil to go further. He won allies in shipping cheap oil to those in need: Nicaragua, Cuba, Haiti and beyond.

Inevitably, Chavez was controversial at both home and abroad. Popular with the poor he allied himself with, many in the richer middle classes felt alienated. Those scenes of undying love and abiding hate will be played out on the streets of Venezuela in the days to come.

But it can be argued that Bolivia, Argentina, Ecuador, and others gained true independence, infected by what he achieved in Venezuela. Obama’s tribute to Chavez and Venezuela this morning speaks not of US control but of US co-operation. It would be a brave writer who would claim that the days of the gringo in Latin America are done. But things will never go back to the way they were before the Chavez era.

For myself, meeting and interviewing Chavez, he was an impossible man to sum up. Ebullient, he was much larger in his being than his small stocky stature described. He ranged from true concern for the poor, to his absolute conviction that he was himself a most remarkable man.

I guess in so many ways he was. His multi-houred telly blather, his tight personal hold on power – while still winning majorities in presidential elections – render him very hard to compartmentalise. My last midnight encounter with him for an interview ended with him singing into the camera.

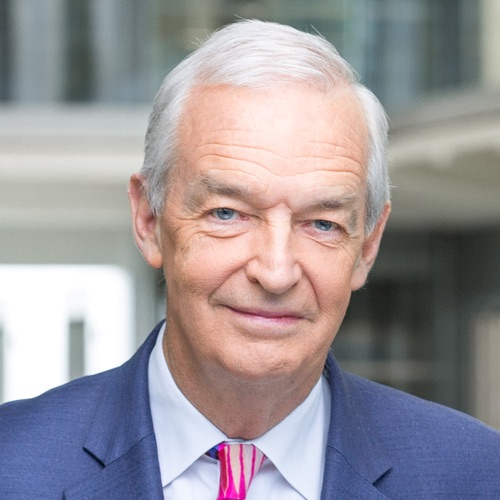

Follow Jon Snow on Twitter