Does Corbyn's run indicate that alienation rules?

I had thought that my own continuing obsession, as a journalist, with the Iraq war was somehow out of kilter with much of the rest of society.

Having travelled to the country during the invasion, and having examined the brutal reality of post-war Iraq five years later, I saw first hand the thoughtlessness with regard to its execution and consequences. But during the global economic downturn and with years of relative calm in the country it felt as if the issue had fallen out of the public’s consciousness.

Strangely, it was covering the referendum in Scotland last year that began to demonstrate to me that despair with the war and Westminster’s role in it was widespread. The genuine engagement that the Scottish people seemed to feel in their political destiny was almost a counterweight to the disenfranchisement that others had felt after the UK’s biggest ever demonstration had little impact in London.

The rise of the self-styled Islamic State, and its repeated savagery, also brought the consequences of the war repeatedly into focus. It seems almost as if every time Isis strikes, a reminder is triggered that in bombing the complex entity that was Iraq, the invading allies helped lay the foundations for this inhuman rebellion. Yet few mainstream politicians discuss the fall-out, even the alienation that flows from both the war in Iraq and in Afghanistan.

Some of the resentment, alienation even, focuses on Tony Blair 12 years on, and not a little of it upon the Labour party in particular and parliament in general. Even though Mr Blair triumphed in the 2005 election, in 2015 very few Labour party figures seem keen to be associated with their three-time election winner.

As visceral as the criticism of the war is, the other and perhaps much stronger sense of domestic alienation focuses on the prevailing policy of austerity. While one poll commissioned by Labour’s Jon Cruddas found that 56 per cent of people agree with the statement “We must live within our means, so cutting the deficit is the top priority”, there is a genuine sense that some of those supporting Jeremy Corbyn are invigorated by the sense of a genuine alternative to the broad consensus among the major parties.

At the general election, the Scottish National Party fought a campaign focused both on war, including the issues of Trident and Nato membership, and austerity. Sure, self-government was a huge issue too, but from what I witnessed, the outcome was far more about those issues than about “nationalism”.

You can dupe some of the people some of the time, the saying goes, but you can’t dupe all of the people all of the time. That has never been truer than in the handling of the consequences of the 2008 banking crisis – of which we have eerie reminders with the continuing tremors in the world markets.

The current government say that their policies have helped the poorest in society, but an undiminishing number of people perceive that the less well-off in society are paying, through these austerity measures, for the mis-doings, avarice, and incompetence of those in the City.

Domestically, some of this sense of alienation has resulted in a surge in fear of the “other”, as expressed in the huge Ukip vote at last year’s general election. For others it led to votes that resulted in the wholesale destruction of Labour, Liberal Democrats, and Tories in Scotland. And for still others it resulted in enthusiasm for the run for Labour’s leadership by Jeremy Corbyn.

Abroad, alienation is expressed in America in support for the TV absurdist and property mogul, Donald Trump, and in Bernie Sanders, one of the few US political figures to describe themselves as a socialist.

In Greece and Spain there are Syriza and Podemos – both of whom have found support on radical anti-austerity platforms. In France it is displayed in the gathering support for the National Front, and in Holland, Denmark, and once liberal Sweden, for support for anti-immigrant parties.

Alienation is what links these disparate movements. Above all, alienation in our digital, connected, social network dominated age, from the old politics focused on the likes of Westminster and Capitol Hill.

These are entities in which voters frequently do not see themselves replicated in the array of elected faces discussing their affairs – despite some high-profile efforts by parties to diversify their candidates. In Britain fewer that 400 women have ever been elected to our parliament since they got the vote in 1918. In both ages and ethnicity these parliaments rarely look like any cross section of the populations in which electors live.

In short, alienation has come to rule beyond the confines of traditional power. Hence, I argue, the Ukip, the SNP and now the Corbyn insurgence.

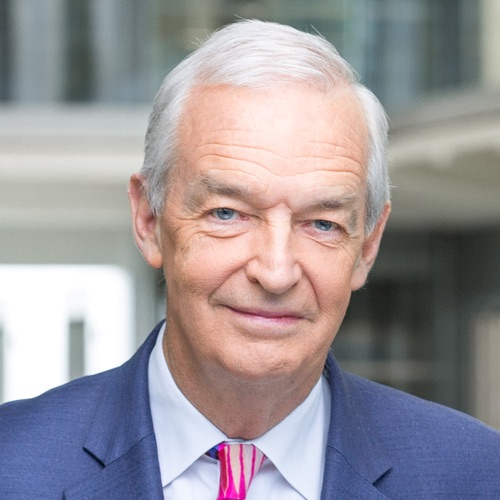

Follow @jonsnowC4 on Twitter