Giulio Andreotti's death puts 'local' politics in spotlight

I awaken to find a light dusting of Etna’s ash on the bedside table. No, I’m not in north London, but briefly in Sicily. My one night in the lee of the volcano, reveals the old beast has been belching fire for a fortnight. One has to take this slightly on trust, because beyond the tiny sooty granules, it’s impossible to tell that the mountain is angry. In an otherwise cloudless sky, the volcano is shrouded in grey cloud interwoven with, but indistinguishable from, grey smoke.

Perhaps Etna heard that Giulio Andreotti was dying, and this morning is pronounced dead – seven years older than Margaret Thatcher when she died last month. Andreotti dominated Italian politics from 1946 to 1992. He was also tried repeatedly for his links with the Italian mafia. Although eventually cleared of numerous charges, the court declared he had indulged in “criminal association” with the “mob” before 1980, but the statute of limitations would not allow prosecution of these matters.

As the FT puts reports today: “In its judgment, the court declared: ‘Senator Andreotti knew full well that his Sicilian associates had friendly relations with some mafia bosses; he in turn cultivated friendly relations with those bosses’.”

So this mafia associate served as Italy’s Christian Democrat prime minister seven times, its defence minister eight times, foreign minister five times, and finance minister twice. None of his postings lasted very long – so short-lived were the governments he served.

Since Andreotti’s last term as prime minister in 1992, the country has been blessed with Silvio Berlusconi’s premierships and manoeuvrings. His media empire so dominates what Italians read and view, that his influence was, and is still, as pervasive as Andreotti’s was. Unlike Mrs Thatcher, Mr Andreotti will be seen off at a private funeral in Rome – far away from Etna’s sooty deposits.

Why do I tell you all this? Because for all the sneering about Italy’s delicate national governance, who else has elected a full time comedian – in this case Beppe Grillo – to dominate a democracy’s opposition?

National vs local politics

The reason Andreotti’s death is important, beyond his mafia connections, is that it underlines a central truth about Italy and in turn about the UK.

The “national” in Italy may indeed be weak, so weak that mafia and “mogul” influence has been commonplace for years.

But the local is strong. When Etna blows, Sicily sorts it for itself; the local is strong and organised – as it is in the virtual city-states of Venice, Naples, Rome, Genoa, Milan and beyond. Strong local government, strong community, strong extended families are the norm. They are the lifeblood of this country.

In effect all real politics in Italy is local. The EU was founded precisely to relate with these regional entities, as it does in Spain and Germany.

In Britain our local is in many ways all but dead. Local politics, as the latest local elections demonstrate, are increasingly national. There are strong pockets like Birmingham and Manchester, but the very fact that 80 per cent of local funding for public expenditure comes from Whitehall, de-links the local from its local voters – hence the terrible turn-out figures.

So we have the spectre of Ukip, a party that appears to stand for very little “local” but for national issues such as immigration and leaving the EU altogether, somehow making a splash at the local level.

It’s one reason why EU regional funding – so common in other countries – is so relatively rare in the UK. The Highlands and Islands, and Devon and Cornwall are noteworthy exceptions.

It’s one reason why many Italians waking to Andreotti’s passing suspect that when it comes to the critical issue of “quality of local life”, it is they who have the last laugh.

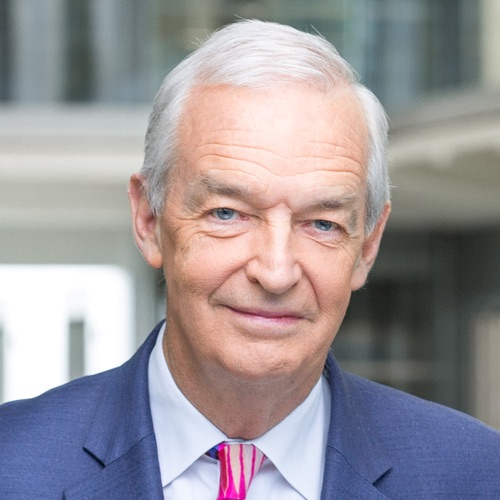

Follow @JonSnowC4 on Twitter