Nelson Mandela: the man who inspired my generation

Over two decades after his “walk to freedom”, Nelson Mandela has walked his final mile.

The impact of his death will reach far beyond the frontiers of South Africa. There will be tears, but celebration for one of the most remarkable lives of our time.

Madiba, as he was fondly known, leaves us with a memory of the best in public life to which any human can aspire. His signal contribution to humankind, the embrace and sustaining of forgiveness for his own, and for his people’s oppression.

Whatever has become of South Africa – the good and the bad since “liberation” from apartheid – nothing can take away from his vast part in the avoidance of bloodshed and civil war.

The transition in which he so pivotally participated – from racial division to equal rights for all – passed smoothly, despite the considerable obstacles in its way. Many of those obstacles have yet to be fully resolved.

But his legacy is global, too. His example has rendered for us all the capacity to talk about race and equality in ways that we could not before.

I was barred from visiting South Africa for many years. My very first flight down to Jo’burg was to witness and report Mandela’s walk to freedom.

More: all Channel 4 News reports on the life of Nelson Mandela

There is already a generation that knows little of what Mandela achieved. But for many of my generation, Mandela’s life and the struggle he led were the cornerstone of our development.

I confess that, in the expectation that he might die, not once but twice have I have flown south, my head awash with so many thoughts. For this was the man who had inspired us as young men and women in the 1960s to make the liberation of South Africa from apartheid our cause.

We marched, we protested, we campaigned. But it was not until a young South African, Peter Hain hatched the “Stop the Seventies Tour” campaign that our cause came to a head.

Sporting boycott

Sport ran through the veins of white South Africa. It was part of the element of white supremacy that underpinned apartheid.

They were good. Good at cricket, good at rugby. They could, and at times did, overwhelm old colonial power in both. Hain and others realised that if South Africa could be isolated in sport, the loss of international competition would go to the very core of the white community – not all of whom felt so supportive of separatism anyway.

So it was that early on a rainy Saturday morning at the Old Trafford rugby pitch where the Springboks were due to play, I found myself armed with a garden spade, digging out clods of earth. There seemed to me to be thousands of protesters swirling about, and a good number of police too.

Soon the demonstration descended into shoving battles with the police. I was arrested and charged with the excessive offence of assaulting a police officer (I was subsequently given an absolute discharge).

At Liverpool University we discovered the place had vast investments in the locally headquartered Tate & Lyle sugar company, which thrived in South Africa with its huge estates of sugar cane – sugar cane that was harvested by dispossessed black workers.

That was enough. We marched for and demanded disinvestment. The university refused to talk. So we occupied the administrative senate bloc. It was a sit-in that initially involved more than 1,000 students, and only the dawning of the vacation brought it to an end. The university moved fast enough to ensure that 10 of us they regarded as ringleaders were expelled before the next term began.

Twenty years on, I was entering South Africa as a reporter to witness the final chapter of the apartheid regime we had so ardently campaigned against.

It was a hugely emotional experience, the more for me than the viewer would ever know. I was live outside the prison gates, craning to catch this first glimpse of a man we had not known or seen in the flesh in our lifetime. We did not even know what he would look life. The last image from 27 years previous was of a black-haired, well-built man – Mandela had been a boxer in his time.

Suddenly, there was a commotion outside one of the low-slung huts some 800 yards from our position outside the gates. Gradually the throng parted to reveal a tall, grey-haired Mandela, unmistakably Mandela, striding with his hand aloft grasping his wife Winnie’s hand.

I cried uncontrollable tears. The Afrikaans journalist standing next to me looked at me askance, dry faced.

Defining struggle

For me, for my generation, Mandela’s struggle defines our time, just as the second world war defined the era which went before us.

This has been a time in which the north has begun to understand its obligations to the south, a time in which more widespread equality between races and sexes has dawned. Our own London is a transformed capital of multiculturalism.

There have been strides in South Africa, too. But as Mandela would be the first to point out, the battle is very far from won. His world was a world in which “white would not dominate black and black would not dominate white”.

Mandela’s death leaves a work in progress, but a work that his life provided an unprecedented impetus to its progress. History will judge: this was a man.

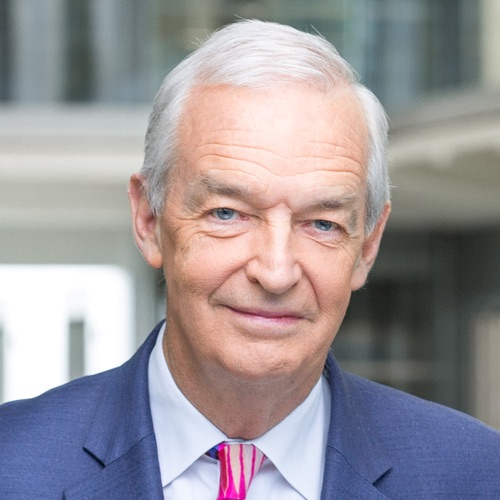

Follow @JonSnowC4 on Twitter