New hope around Iran and a conversation with Tehran

Matters with Iran are at last on the move – after too many years of a proven bankrupt policy of non-engagement and a bullying sanctions regime.

Much of the policy on Iran has been driven by America, and beyond that by considerations of Israeli concerns about Iran’s developing nuclear programme.

At no point has anyone yet proved that Iran is building a nuclear bomb. Circumstantial evidence has been brought forward, but absolute proof has been in seriously short supply.

The United States has never recovered either from the Islamic revolution which overthrew its over-faithful ally, the shah.

More importantly, the US has never recovered from the humiliating seizure of 52 of its diplomats and its embassy in Iran a few months after the revolution itself. The hostage crisis lingered for 440 days and its after-burn of mistrust continues to this day.

Britain has enjoyed relations with Iran for several centuries until its embassy was invaded three years ago by rock-throwing hooligans. The incident did not appear to have been officially sanctioned, but the government nevertheless failed to get it under control, and the UK effectively broke relations.

Today, suddenly, a meeting between the British foreign secretary and Iran’s President Rouhani appears possible in the margins of next week’s UN General Assembly. Back channels of diplomatic activity have been reopened between Washington and Tehran – in part precisely because of the election of President Rouhani, and in part because of the escalating diplomacy surrounding Syria.

All this against a backdrop of the past 12 years in which vast events have unfolded on Iran’s porous borders: protest in Turkey, war in Afghanistan, war in Iraq, and, a country away, war in Syria.

To all these conflicts this great regional power has had the potential to play a huge diplomatic role – but it is a role that has been frustrated by the failure of talks about Iran’s nuclear programme.

Unlike India, Pakistan, and Israel, Iran is an active member of the nuclear non-proliferation treaty. It has abided by some of its rules, allowing sporadic inspections, and not by others. But above all it is part of a mechanism that has brought about both inspection and dialogue – something that has not happened with any of its nuclear near neighbours.

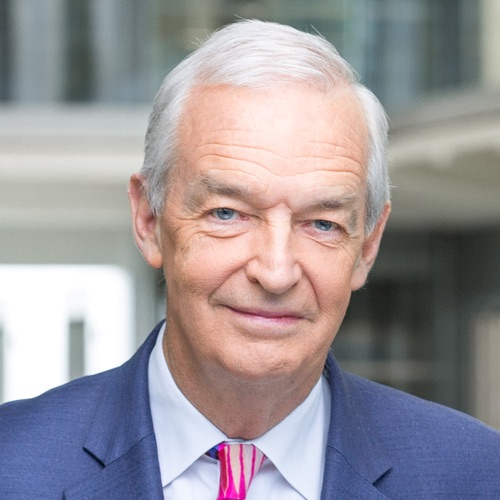

Yesterday I had the opportunity to talk to Professor Mohammad Kazem Sajjadpour out of Tehran (see video).

He’s a professor of international relations in Tehran and has close contact with President Rouhani. We explored the relationship between the new opening to Iran over Syria and the stalled nuclear talks.

His conversation with me was highly instructive and, I would argue, extremely encouraging.

Follow @JonSnowC4 on Twitter