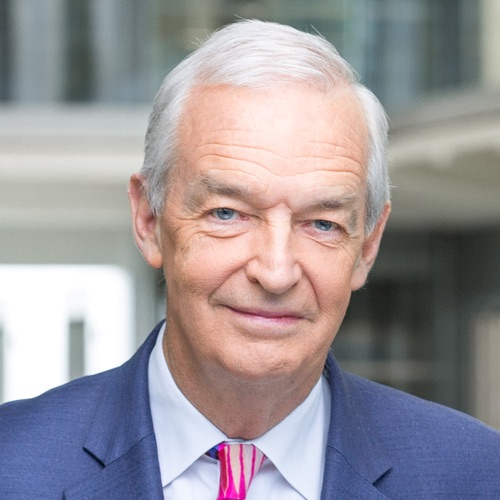

Jon Snow, on his own involvement in protests at Liverpool University 50 years ago

Next Saturday, Liverpool will be the scene of another street protest about racial inequality. Liverpool, like Bristol, steeped in a history of slavery and racial tensions.

So it was that in 1968, when I was a student at Liverpool University and we protested against the chancellor of the university. Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, fifth Marquess of Salisbury Lord Salisbury, had been in post ever since 1951. He was the scion of a family that had feasted on white supremacy, and ravaged the mineral and other riches of southern Africa. The name ‘Salisbury’ adorned the capital of what was then Rhodesia, and is now Zimbabwe. Indeed, he supported Ian Smith’s illegal, racially motivated regime at the time.

The university authorities were scandalised that we should question the fitness of his lordship to be the chancellor of a multi-racial university. We wanted him out. The university authorities wouldn’t talk with us, so we seized their brand new senate block from which the university was administered. The authorities would not talk with us. After some ten days, the six hundred or so students ‘sitting in’ deputed me to go to Liverpool’s Lime Street Station to meet the train upon which Lord Salisbury was due to arrive in the city. I was chosen because I was said to have a posh voice that he might find easier to understand.

The train from London arrived and out tumbled Salisbury. “Excuse me, my lord, could I have a word,” I asked. Then I blurted out: “My lord, my name is Jon Snow. I have come to tell you on behalf of the Students’ Union that if you venture onto the campus, your presence could ignite a riot.”

“Why don’t you come and take tea with me, and we can talk about it,” he said. Thus, in amongst the marble pillars of the Adelphi Hotel, we were served with Earl Grey tea and cucumber sandwiches. I was concerned that I might be spotted, supping with the devil. But at the end of it all, he declared: “Very well, I shall not come to the University, indeed I shall never come there again. I shall resign. Indeed, Mr Snow I’ve never much liked coming to Liverpool anyway.” And with that he, and his retinue, made for the station and the London train.

Today’s students have many colonial names and establishments in their sights. Not least Gladstone Hall, a student hall of residence in Liverpool. As prime minister, William Gladstone Gladstone spoke out against abolition because his own family had slaves in the Caribbean. His father, John, was a slave trader and benefactor – like Edward Colston in Bristol, whose statue now lies beneath the waves.

Looking back, we were offended by the involvement of a man – who still embraced racist attitudes – in the running of a seat of learning. The lesson too, is that that the misdeeds of these people must never forgotten. At school I was taught about the great abolitionist, William Wilberforce, but not about Edward Colston or John Gladstone and their profits from slavery. Our curriculums owe it to all of us that Britain’s historical mis-deeds are remembered and learned from.

As for the degree I never got, Liverpool University generously gave me an Honorary Doctorate in Law, five years ago – the subject I was reading. I am as proud of that as I am of having protested when I did. My only sadness is that another generation is now having to wrestle with the unresolved issues of race and inequality that fuelled our own protests half a century ago.