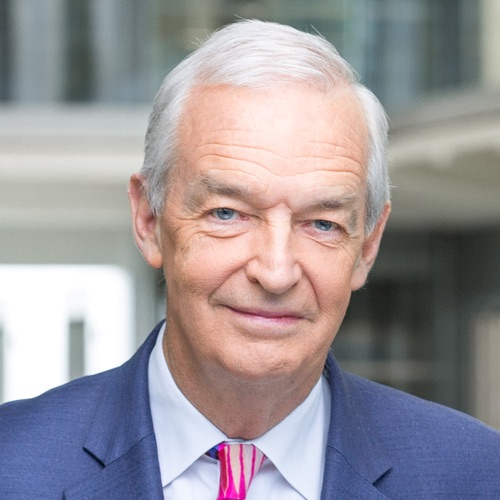

Jon Snow on his return to Zimbabwe

He threw me out in the eighties, and until now I had never been back. I thought it wise to wait until the old man had been dethroned, or had died. African potentates don’t come much worse than Bob Mugabe. A man who blew his formidable intellect in the pursuit of absolute power. One tends to forget his four or five degrees. But not his violent, ruthless, and once seemingly unstoppable reign.

Soon after arriving in Harare, I drove past his plush domestic exile. For he continues to languish in his opulent ‘Blue House’ in the outskirts of the city, where, for so long, he spent much of his Presidency. Today he is naked of power, denuded of title. But spare no pity but for him, aged and infirm he may be, but he’s wallowing in wealth – and the deal that brought about his defenestration leaves him safe from prosecution.

For his avaricious wife Grace there is no such amnesty. The forces of law enforcement are gathering beyond her tasteless compound on the other side of town. She is on a deadline to yield up her vast gains. Her ostentatious spending of this ruined country’s money knows no bounds. At the end of last year, she bought her two wayward sons a spanking new Rolls Royce each. They were shipped from Europe through Namibia. As soon as they arrived in Zimbabwe, the sons set about driving them out again to put them beyond the reach of the of the State as it now seeks to retrieve the family’s ill-gotten gains. But as the boys drove the cars toward the border, one of them crashed it, rendering it a total write-off. Grace is unlikely to keep her pecuniary liberty for long enough to secure another.

Enough of the sad bad stuff.

For where once arriving at Harare Airport as a foreign correspondent was a nail-biting experience, these days the sparsely populated arrivals hall is ordered and relaxed. Flights are equally sparse and rarely full. But it’s here that the country’s biggest immediate crisis becomes apparent.

An entry visa costs $55. But does anyone have the $5 that the immigration officer needs to give change for the $60 proffered by the passenger in front of me? Someone in the queue finally produces some change. The dollarization of the currency a decade ago has proved a disaster. The introduction of the ‘Bond’ note to make up for lack of dollars has been no solution either. Having started at parity, it now trades at anything up to 1 Bond 50 cents for the dollar. You feel the consequences everywhere you go.

But these days, spirits in Zimbabwe are high. The old despot is gone, and that alone has raised hope. The fact that a lot of his old muckers are still around seems to do little to weaken it. Some of Mugabe’s old cronies are in post but no longer in power.

The whole country appears to accept that power will flow only once ‘free and fair’ elections are held. Where once police set road blocks at intervals all over the country as a means of political control and providing themselves with pocket money, today there are none to be seen – to the palpable relief of the people. Today in the cities – Harare, and Bulawayo – once again you suddenly notice police officers holding up the normally wayward traffic to escort children across once ignored crossings to school.

Mugabe’s removal and getting rid of the road blocks have combined to add to the sense of freedom and wellbeing, even if the dire economic conditions are unchanged.

Zimbabwe is one of the most irresistibly beautiful countries in Africa. Despite the horrors and abuse in its past it is a country that presents as primed for success. Despite Mugabe, much of the population is educated. Indeed, for all the erosion of budgets, both Primary and Secondary schools continue to achieve high standards, with a remarkable number of students going on to University, here and abroad. Hence the remarkably strong diaspora of Zimbabweans who were forced to leave Zimbabwe in Mugabe’s time in search of a better future.

They also represent a real resource if and when the country really opens up.

In this, a country the size of Germany, the population is only thirteen million. Mugabe reduced a country of food abundance to an entity in which half the population depend today upon international food aid.

Zimbabwe’s relative emptiness strikes you on any journey you take. You can drive for miles and miles of verdant country and rarely see a soul.

Potential abounds. The Population these days is 82% Shona 14% Ndebele. It is a cohesive society. The bloodshed between Shona and Ndebele of the last century is stilled. Inter-marriages seem to have healed much of the factional past. These days there are fewer than 35,000 whites, and no evidence of significant inter-communal friction.

The country cries out for good governance and investment. Interim President Mnangagwa, despite his own chequered past, has made some intelligent commitments, but everyone here will take time to trust power in any form. Mnangagwa has pledged to allow EU and UN monitors for the election and has promised to step down if defeated. If he wins, he will also have to weed out the remnants of Mugabe’s tyranny. Good governance however needs a strong opposition. But no one has so far come up with a figure to either lead it, or even to win the day.

Nevertheless, the feeling I’ve encountered is one of hope that what you see with Mnangagwa, could just be what they’ll get. A sort of official acceptance that the past failed and failed badly. There have been signals too that have embraced the private sector, a reconnection with the UK and the Commonwealth; and becoming active members of the Africa Union. The Mnangagwa mystery is HOW, and How quickly, and whether, in the end if it is not he who prevails, who will.

If Zimbabwe’s natural resources, wide open land, and plentiful human capacity stand for anything; if the elections do turn out to be free and fair; then the future for this country could prove a dramatic contrast from its past.