For any new Pope: the challenge of the Vatican Bank

Nothing so defines the mystery and suspicion that lies at the heart of the Catholic church than the Vatican Bank. For all its secrecy and lack of transparency, you might think St Peter had set it up himself. In reality it was set up in 1942. Today it symbolises one of the core practical challenges for any incoming Pope.

Since the bank’s foundation, it has seen suicide, unexplained death, allegations of money laundering for the Mafia, and seen priests and several of its own directors investigated by US and Italian fraud and organised crime police.

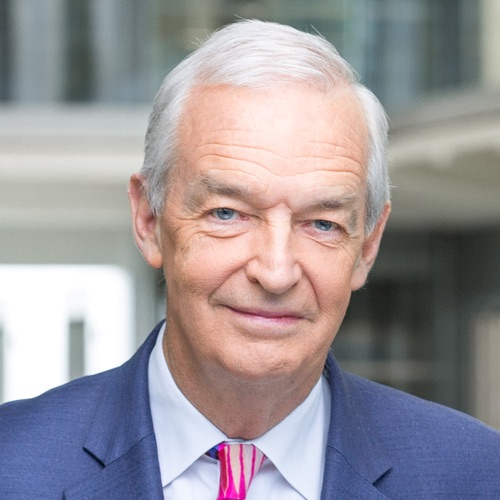

When I was based here in the late 1970s, an American archbishop led the Vatican Bank, Paul Marcinkus. I met him several times. He exuded an eery air of arrogance and self satisfaction.

As far back as 1973, Marcinkus was questioned by a US federal prosecutor – William Aronwald, and the head of the US organised crime and racketeering section of the US Department of Justice. As head of the Vatican Bank, the US authorities wanted to know what Marcinkus knew about fake bonds totalling $14.5m, which had been delivered to the Vatican Bank in 1971. They had uncovered a demand on Vatican headed notepaper for $990m of the stuff.

A freelance journalist, Mino Pecorelli, whom I had met and talked to about the bank, and who had been investigating Marcinkus himself, was found dead in mysterious circumstances in 1979.

It was at this point that the US authorities gave up on the bank, having failed to penetrate its extreme secrecy. But then in 1982, the body of Roberto Calvi, head of the collapsed Banco Ambrosiano, was found hanging from London’s Blackfriars Bridge. Once again the Vatican Bank and Marcinkus were in the frame. It transpired that surprisingly this grand cleric had been an overseas director of the bank located in an office in the Bahamas. Italian police tracked activity involving Banco Ambrosiano to both the Mafia and a masonic lodge in Italy. The Vatican Bank denied any involvement but still paid out $25om to Banco Ambrosiano’s creditors.

Marsinkus died seven years ago, his secrets went to the grave with him.

Ironically, it was the birth of the euro, and Italy’s decision to join in 1999, that forced the Vatican Bank’s hand. They had to join too. Assorted EU officials have described the intense difficulty in persuading the bank to comply with EU anti-money laundering regulations.

The truth is that during the Cold War the Vatican Bank had proved a convenient conduit for laundering money to anti-communist movements beyond the Iron Curtain. There was a culture of international permissiveness where the bank was concerned.

It was only in 2009 that the Vatican Bank finally signed up to the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice for the settling of disputes involving their compliance with EU rules. The bank’s director told reporters that it did so in order to be able to continue issuing euros emblazoned with the image of the Pope.

But the trouble with the bank continued. The Bank of Italy this year put a block on Deutsche Bank Italy from managing any financial activities on behalf of the Vatican Bank. This was because the Vatican had failed to meet another deadline for signing further compliance agreements with Brussels.

Interestingly, one of Pope Benedict’s last acts was to remove the bank’s Italian director and replace him with an outsider – a German aristocrat. The previous incumbent had come under huge pressure after a case with the Italian authorities in which 20m euros had been impounded by magistrates concerned with its origins. The cash has now been released.

But talk to anyone in this town, and no-one is convinced that a bank, designed to hold the donations and gifts of the faithful, is yet complying with the highest spiritual and temporal aspirations of Catholic worshippers.

Follow @jonsnowC4 on Twitter