'Pragmatic' Britain must review its strategic lines

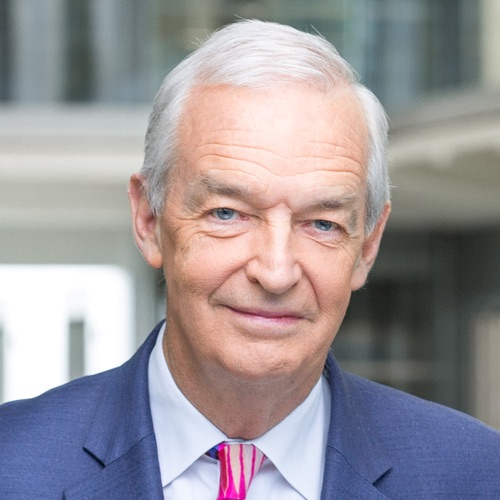

Sergio Romano is one of the most respected journalists and writers in Italy, writes Jon Snow. He writes a regular column in Corriere della Sera that regularly provides rich fuel for the public discourse. Below I have attached his wonderful analysis of Britain’s relationship both with the US and the EU.

I was asked to play a game that was remarkably played by a Russian exile, Andrej Amalric, the author of a book which was published in 1969 under the title “Will the USSR survive until 1984?” He was wrong by eight years, and unfortunately he had already died in a car crash in 1980. Let us see what I can do with the subject of this exercise.

I lived in London for six years between 1958 and 1964. When I arrived, one year after the signature of the Rome treaty for the establishment of the European Community, the vast majority of British public opinion thought that European integration was not for the UK and was convinced that the continental boat, any way, would not sail. In fact, the government of Harold Macmillan was soon going to build another ship called Efta, which would collect the shipwrecked countries of the Common Market.

I do not have to recall what happened. A few years later the British changed their mind and would have joined the countries of the Common Market even more quickly if the process had not been slowed down by the stubbornness of General de Gaulle.

I have recalled this episode because I want to make clear that the Britain I have known was a pragmatic country where governments did not hesitate to change their mind when they discovered that they had made a mistake. Of course, it was clear to me from the beginning that Britain did nor share the federal philosophy of the original founders and had become a member better to control the process from inside.

From then on, the British government had to adapt its policy to the changing conditions of Europe, but was basically consistent with its original intentions: yes to the single market, no to any development which would imply an important loss of sovereignty, especially in the areas of foreign and monetary policy.

As to the reasons for this attitude, I prefer to leave aside the usual cultural explanations: national pride, a sense of moral superiority, the imperial past, well-rooted distrust for the ways and manners the countries south of the channel. I am not very good at measuring irrational and emotional attitudes. I’d rather stick to what I can understand and suggest that the UK had two debatable but reasonable motives to pursue the policy it has systematically pursued since the day it entered the European Community.

The British were convinced that they would preserve the special relationship with the US, formed during the war, and that they would play a major political role as the indispensable linchpin of a great Atlantic community. They were also convinced that the experience of the city, combined with the opening of the financial markets since the eighties, would justify the preservation of the national currency and allow London to be, with New York, a world economic and financial centre.

Are these two arguments still valid? The special relationship has dragged the UK, as a major partner, into the American conflicts of the last decade: two catastrophic wars that have been practically lost and have also greatly worsened all the troubles of the region. The financial crisis originated in the US and has proved that it is not wise to imitate a country where the government has lost control of its bankers.

The two events should persuade the British that the time has come to review their strategic lines. They may very well come to the conclusion that they were wise not to mingle too much with the European monetary union and other federal plans originating in Brussels.

But they should take into account a trend and a possibility. The trend is the American decline as a superpower and the wave of neo-isolationism which is growing in American society. The possibility is that Europe may overcome the crisis of the euro and come out of the test stronger and more federal. The pragmatic Britain which I have known in the sixties may very well decide that Europe, after all, is a good investment. And if it decides otherwise – well, too bad, but we shall survive.

Follow Jon on Twitter via @JonSnowC4