Return to a sombre, less vibrant Iran

There are still streaks of snow lying on the tops of the Alborz mountains above Tehran. The city below already basks in a summer constant of 28 degrees. The traditional smog levels are down – one rare positive consequence of one of the most draconian sanctions regimes the world has ever known.

On the Lufthansa flight in here, I thought about the more than 30 years of travelling in and out of Iran that I have experienced. The German carrier was jam-packed with passengers – mostly Iranians now domiciled in the USA. Their little American children ran about the gangways sporting their American sports tops.

//

Talking of tops, as we boarded in Frankfurt I counted fewer than five of the dozens of women passengers with head coverings. We ourselves stood out as white Europeans. As we landed there was plenty of quick change in evidence. It is against the law in Iran for women not to cover their heads in public.

This is business that British Airways once used to dominate. Not any more – it doesn’t even fly here. Its business has been seized by Lufthansa’s daily flights; by Turkish Airlines, which runs a virtual shuttle from Istanbul of five flights a day; and by Emirates via Abu Dhabi.

On the car-jammed streets, the vehicles, which once hailed from Scotland’s Linwood, are now French and Japanese or built by the Iranians themselves.

British Airways joins a myriad of much smaller manufacturing companies across the UK who have been deprived of their historic trade with Iran by the American- and British-led international sanctions against this country. High-end sanctions like cars and plane journeys make little difference to Iran’s vast swathe of rich who live within Iran or in comfortable exile in California, Britain, Switzerland and beyond. It extends their journeys home but little more. But for the poorer masses, sanctions have savage consequence. Food price inflation is running at an admitted 25 per cent. A butcher in the bazaar told me on Sunday that the prices of chicken and lamb have doubled in a year.

For the rest, industrial and commercial spares are in dangerously short supply. The cost of all this to the Iranian people is undoubtedly very high. The cost to British and other suppliers has crippled many small and medium-sized export businesses across the world.

Nuclear issue

Yet here I am, starting to cover a presidential election in which the nuclear issue, with which the west is obsessed, is not on the agenda at all. So even if the “masses” wanted a change of heart over it all, there is no candidate offering one.

Despite the revelation over the years of a number of underground nuclear facilities which Iran had kept hidden from the IAEA, as the journalist Peter Oborne and the academic David Morrison point out in their new book, A Dangerous Delusion, the west has still failed to prove that Iran has a nuclear weapons programme.

The 40-year project (still unfinished) to build a nuclear power station here at Bushehr requires enriched uranium. Iran’s developed industrial base is capable of producing it and like the UK, the US and many other countries have set out to do so. The west perceives Iran to be a threat to the rest of the world and cannot reconcile itself to any step that might enable it to develop the capacity to make a nuclear weapon. And that is where Iran and the world are stuck.

On the surface, Tehran thrives: the traffic as dense, the bazaars as jammed. But the atmosphere is more sombre, the opposition silenced, and the once vibrant spirit of the people lessened. It does not strike the visitor as a great way to do business either for Iran itself or for the international community.

Yet it still does not seem to be beyond the wit of humankind to find a way of bringing this pivotal regional power back where it belongs in the family of nations.

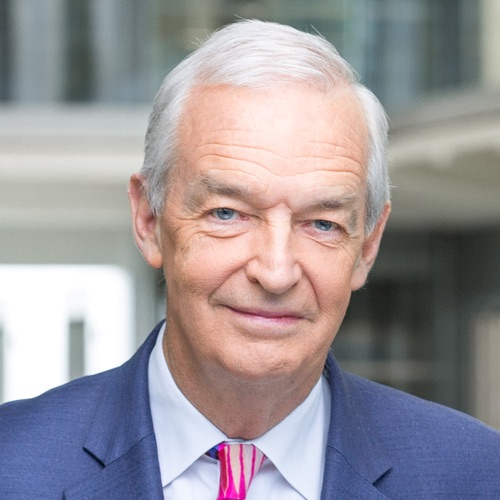

Follow @JonSnowC4 on Twitter