Somalia's famine: their agony and our historic part in it

There were Italians, there were Yemenis, there were Zanzibaris and there were Russians. We mingled in the hot streets of Mogadishu, or bumped into each other in the Italian restaurant across the street from the old stone built Croce del Sud Hotel. Or we might see them on the beach looking out across the port. The Somali capital was a place of intrigue and conflict. The year was 1976 and I was on my first foreign assignment to try to find out whether Russia or America was now in the ascendent in Somalia.

A hot, parched, pivotal nation, at the bottom end of the Red Sea – to visit Somalia was to risk losing your heart to her. The people were poor, but open, welcoming, and breathtakingly beautiful. By the sea they fished. Inland, they scraped a wandering farming living, entirely dependent upon rare bouts of rain.

But Somalia was also a war-ground for the outside world. Who ruled in Mogadishu mattered. Bullied and manipulated before independence, by colonial Britain and no less colonial Italy, the atlas said it all. Some official had grabbed a ruler and drawn a straight line across the Ogaden desert, dividing Ethiopia from the Somali flat lands. For the endlessly wandering nomadic peoples of the Ogaden, which side of the official’s ruler you meandered mattered not.

Somalia was ripe for rape, ripe for howitzers and the other barbarous plumbing that the outside world would import to resolve their arguments about who controlled the gateway to the Indian Ocean.

We cub reporters were in on the birth of Somalia’s agony. The country was deemed too lowly to send a senior reporter and so we boys were sent to get lost for weeks upon end to return shaggy, dusty-haired and browned from the eternally searing sun, to report our findings.

We were in on the foundations of her present pain and suffering. We found the outside world rendering her fledgling governance a nonsense. We found the British, Russian and American embassies by turns wielding more power than the President, and rarely in the interests of the indigenous people. No wonder even the hard faced Communists of Siad Barre’s menacing regime crumbled. No wonder the country splintered back into its tribal past. And amid the dawning of ever more acute shortage, no wonder they came to fight each other. And as each successive outside influence – capitalist, communist, Islamist – came to call with cash and weapons, no wonder they accepted both.

No wonder then Somalia became the most dangerous war ground in the world; no wonder her seas the unsafest on the planet.

Read more from Jonathan Rugman, writing from Kenya on aid efforts

One of the great tough-guy leaders of Africa – Flight Lieutenant Jerry Rawlings (who became Ghana’s President with a coup in 1981 and bequeathed a democracy to his successor in 2001) is today the African Union’s Envoy to Somalia.

No wonder Rawlings cried in Mogadishu on Channel 4 News last night. His day had been consumed with dead children, starved of their lives. Somalia is their crisis and our moral burden.

We, the outside world were there. We fiddled, we manoeuvred, we manipulated to safeguard the energy of our lives, the safe transport of the world’s oil. Now it is pay back time, and Rawlings is calling forlornly from a wrecked quarter in Mogadishu, with an armed soldier at his back.

“Bring your food, your medicine, your help. Hundreds of thousands are in peril of death in the next two, three, four weeks.”

The United Nations is at his back, warning the famine is spreading. The factions on the ground are so weak and enfeebled that they are laying down their arms with arms that can now barely lift them.

Famine is not remote. Famine is us, our history, our involvement and calls down our duty.

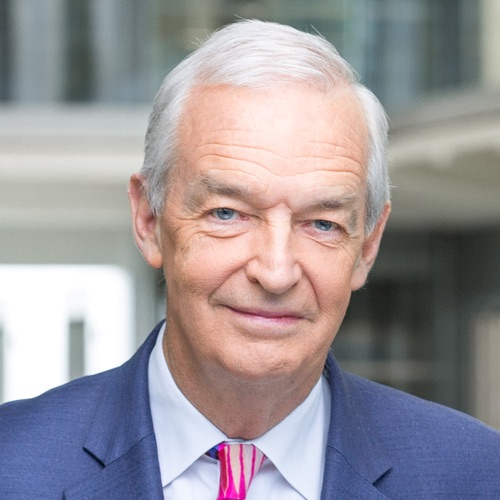

Follow @jonsnowC4 on Twitter.