Sri Lanka: trouble in paradise

Canada was clear – staging a Commonwealth leaders’ summit in Sri Lanka would be a very bad idea. The Canadians argued strongly against it, eventually deciding to boycott it altogether, and threatening a significant withdrawal of funding from the Commonwealth secretariat. After all it was only last March that the Queen signed the Commonwealth charter committing the organisation to respecting human rights; good governance; democracy; and respect for the rule of law. Selecting a country whose government has been in spectacular breach of each of these commitments to host the first summit after the signing of the charter was bound to leave a strong stench of hypocrisy hanging over the affair.

“Is there anyone here with a question about anything other than Sri Lanka and human rights,” asked the exasperated Commonwealth spokesman in desperation. This after two of the big set piece news conferences had been dominated by discussion of war crimes allegations, disappearances, and sexual crimes committed by the country’s military. New Commonwealth commitments made at the summit to set up global youth programmes went by un-remarked.

This turned out to be the worst attended Commonwealth leaders’ summit on record: 25 of the 53 presidents or prime ministers stayed away. There were also very few Commonwealth journalists here to cover the event. The exception was from Britain where all four major television news outlets sent teams who until now had been denied visas to report the aftermath of the country’s civil war. An aftermath in which the armed forces, the president and his brother, the defence minister, stand accused by the UN of massacring some 40,000 of their own people.

Hence the entire summit proved a strange event indeed.

Roads, buildings and even the conference centre itself had all been built or refurbished by China, in a headlong dash over the past six months. This must go down as the first event effectively born of the after-burn of the British empire to have been bank-rolled in part by the communist Chinese.

Over it all presided the neo-Episcopal dressed figure of President Mahinder Rajapaksa and his brother, Defence Minister Gotobhaya Rajapaksa. It’s these two men who have been most implicated in the shelling and bombardment of the “no fire zone” they established at the end of the civil war.

After President Rajapaksa broke his own constitution by summarily sacking Sri Lanka’s respected chief justice in January, the Commonwealth Secretary General Kamalesh Sharma had little option but to have the matter investigated – it represented a prima facia reason for moving the summit elsewhere. The investigation lawyers, who included Britain’s Sir Jeffrey Jowell QC, concluded that the matter had been a serious breach of the rule of law. But that advice was never shown to the eight Commonwealth foreign ministers who had to make the final decision as to whether to go ahead with meeting in Sri Lanka.

‘Shine a light’ on allegations

Britain found itself between a rock and a hard place when it came to the decision to attend the meeting. The UK could hardly boycott an event which Prince Charles was to open (the Queen having been stealthily absented from the thing at an early stage in its planning). David Cameron’s alternative was to attend, albeit briefly, and to use the moment to “shine a light” on what he termed the “appalling allegations of human rights abuses and war crimes”. Having seen Channel 4’s film “No Fire Zone”, the prime minister was in no doubt that he needed to challenge the Rajapaksas. And so, it seems, he did.

China’s ascent in Sri Lanka has rendered British influence here much diminished. Nevertheless, Mr Cameron did a brave job, engineering an unprecedented trip to the north of the country – the first by any outside leader since 1948. In so doing he triggered the only images that spoke to Sri Lanka’s still unresolved recent past.

Consequently boycotts, non-attendances and discussions of Sri Lanka’s alleged war crimes – and crimes against humanity – obliterated everything else. Even some of those who did attend, left early. This was, I can testify, a shambles of a meeting. Staff in the Commonwealth secretariat who had seen it all coming, were in despair by the end.

But the Rajapaksas had their day in the sun. Surrounded by whirling dancers, cascades of fruit and trinkets, and ever present poster’s portraying both brothers, they could look forward to flaunting the ensuing photographs of hand-shakes and bowing, to prove their acceptance at the top table of the family of nations. But whether the after-glow of it all will prove enough to overwhelm the furore stirred by the renewed publicity surrounding human rights abuses and alleged war crimes on the island, is very much in doubt.

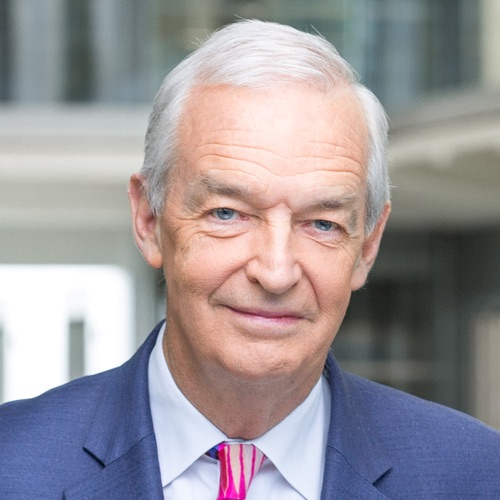

Follow @jonsnowC4 on Twitter