The loophole that could protect countries with something to hide

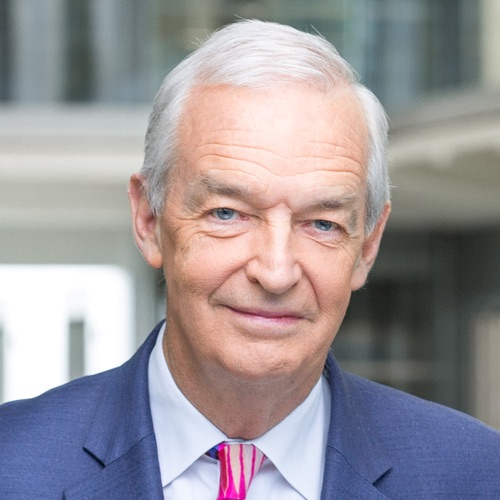

Jon Snow’s article first appeared in the Guardian newspaper.

The scandal of Britain’s libel laws and their facility for libel tourism is well known. So too is our traditionally cavalier attitude to freedom of speech.

But even against this background, the idea that a country with one of the worst records for press freedom and human rights was able to use the UK’s broadcast regulations to challenge legitimate reporting of allegations about cold-blooded killings in a brutal civil war surely takes the UK to a new place.

Whatever private individuals and corporations may be able to do, our legal system does at least prevent states, governments, and political parties from suing for defamation in our courts.

I and my colleagues at Channel 4 News are emerging from a storm that saw Sri Lanka bypass our libel laws and attempt to use Ofcom, the broadcast regulator, to do what the law would not allow – silence our journalism.

Ofcom’s job is to protect “people who watch television and listen to radio from harmful or offensive material” and to further the interests of UK citizens in respect of communication matters. It does this well.

Ofcom’s job has never been to protect governments or organisations from criticisms or to further their political or commercial interests.

Last year, we broadcast a video showing nine bound and naked men, two of whom were shot, on camera, by soldiers who appeared to be wearing Sri Lankan army uniform.

On the night in question the script made clear that while we couldn’t authenticate this video, sent to us by a group called Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka, it nevertheless raised matters of such importance that further investigation was warranted.

The Sri Lankan High Commission immediately denied the atrocities that the video appeared to show.

Two weeks later, at a news conference in Colombo, Sri Lanka said “independent” analysis had declared the video a “fake“.

It mounted a high-profile global campaign to discredit the report, protesting outside Channel 4’s London headquarters. The Sri Lankan government opened up a second front in the UK, filing a series of complaints with Ofcom – one for accuracy and impartiality, one for fairness and privacy.

What had begun as a media campaign to try to destroy the credibility of the Channel 4 News report had become a private battle using the UK’s broadcast regulator. It was a battle in which they were initially allowed to hide anonymously behind the confidential nature of the procedures.

In the end, battle was spared by the findings of a UN committee which recently concluded that the “offending” tape did appear authentic, and dismissed Sri Lanka’s analysis.

Strangely, on the eve of the UN report’s publication the government of Sri Lanka dropped its Ofcom complaints. Whether it had got wind of the verdict, we do not know.

The Sri Lankan video affair has revealed how the Ofcom procedures are potentially open to abuse that threatens to curb not only investigative reporting, but coverage of countries who have repressive and litigious trouble spots and who would rather hide this from public scrutiny.

In short the way Ofcom’s complaint procedures are framed raises serious implications for the reporting of issues of global significance,

Ofcom has come of age in my reporting life time and I regard it as an unexpected regulatory success. But we all need to look to the very real risk of governments “hijacking” the regulatory process for their own political ends.

In this case, Ofcom was placed at the centre of an international row over Sir Lanka’s human rights record and was being asked to take decisions which could have had a major bearing on the country’s attempts to defend its reputation. This cannot be a proper use of the Ofcom process and nor can this be in the interests of UK public at large.

Before Sri Lanka’s complaints were dropped, we were prepared to put these arguments in front of a court.

We felt a clear ruling that denied countries access to Ofcom’s complaints procedures would be beneficial not just too political debate in the UK, but would also help the regulator to avoid being drawn into major international crises. In the absence of a legal ruling, only parliament can change the basis on which complaints can be brought to Ofcom and we urge them to find time to do so.

Without such clarity, we have a serious concern that other countries could follow the Ofcom route.

Ofcom surely needs to ensure that Sri Lanka is the last country ever to be allowed to attempt to pervert the regulator’s domestic complaints procedure for its own reputational needs.