Why I criticised Met Eireann for naming Storm Fionn

There’s no doubt that the weather for the UK and Ireland has been very lively this week, with a powerful jet stream driving areas of low pressure across the Atlantic Ocean towards us.

This has graced our shores with a meteorological melange of rain, hail, sleet, snow and strong winds, bringing the usual array of disruption that would be expected during the winter months.

Weather warnings have been issued by both the Met Office and Irish Met Service, Met Eireann, who work around the clock to provide the latest weather information.

On Tuesday, in addition to an amber wind warning for the west coast of Ireland, Met Eireann named Storm Fionn, the sixth named storm of the autumn/winter season.

If you follow me on Twitter, you may have seen that I criticised their decision to do so, for reasons which I included in my tweets.

#StormFionn that has been named by @MetEireann shouldn’t have been named. It needs no more than a standard weather warning. It’s not even a low pressure with a storm centre, just a squeeze in the isobars. What next? Naming raindrops? It’s ridiculous! pic.twitter.com/WylG2Ym65d

— Liam Dutton (@liamdutton) January 16, 2018

A flurry of responses followed my criticism – some agreeing with me, others disagreeing.

Given the level of interest this has generated, including from the Irish media, I wanted to take the opportunity to expand my thoughts and reasoning behind my criticism beyond the 280 character limit of Twitter.

Why are storms named?

Just for a bit of background, storm naming is a joint initiative by the UK and Irish meteorological services to raise public awareness when severe weather is expected – currently in its third season of operation.

Whenever a deep area of low pressure (storm) has the potential to cause an amber or red wind warning to be issued by the Met Office or Met Eireann, it is given a name from a list decided upon before each autumn/winter season starts.

Admittedly, as with any new initiative, it got off to a bit of a rocky start, with storms being named too easily. But now in its third season, it has generally found its feet – although there are still, as demonstrated by my criticism on Tuesday, cases where storms are named (in my opinion) unnecessarily.

The reasoning of my criticism

The main reason that I disagree with Met Eireann naming Storm Fionn is that there was no storm in the sense that many of us would consider a storm.

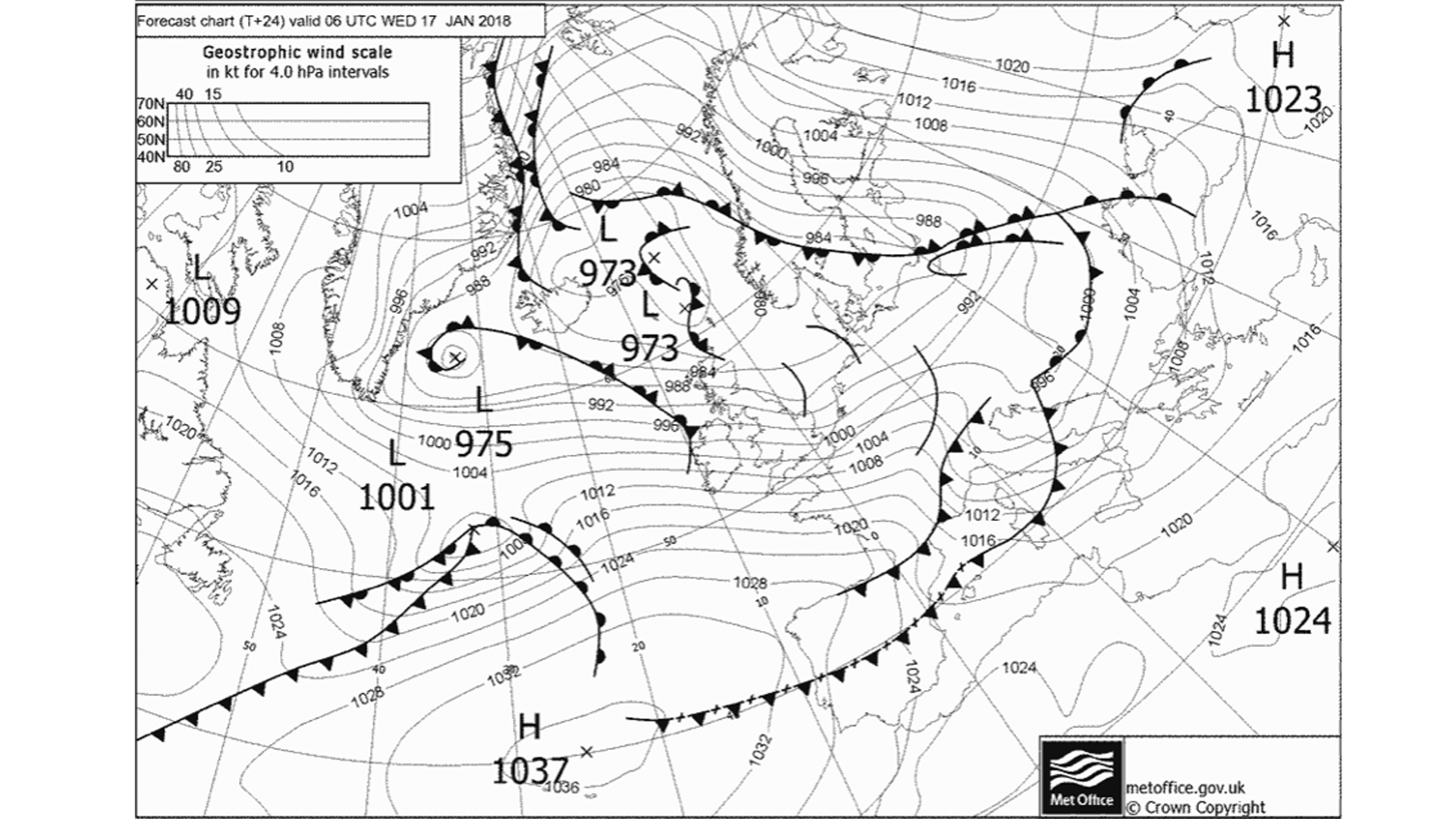

A look at the pressure chart for Tuesday shows no marked low pressure anywhere near Ireland. The nearest marked area of low pressure is located 500 miles northwards, east of the Faroe Islands.

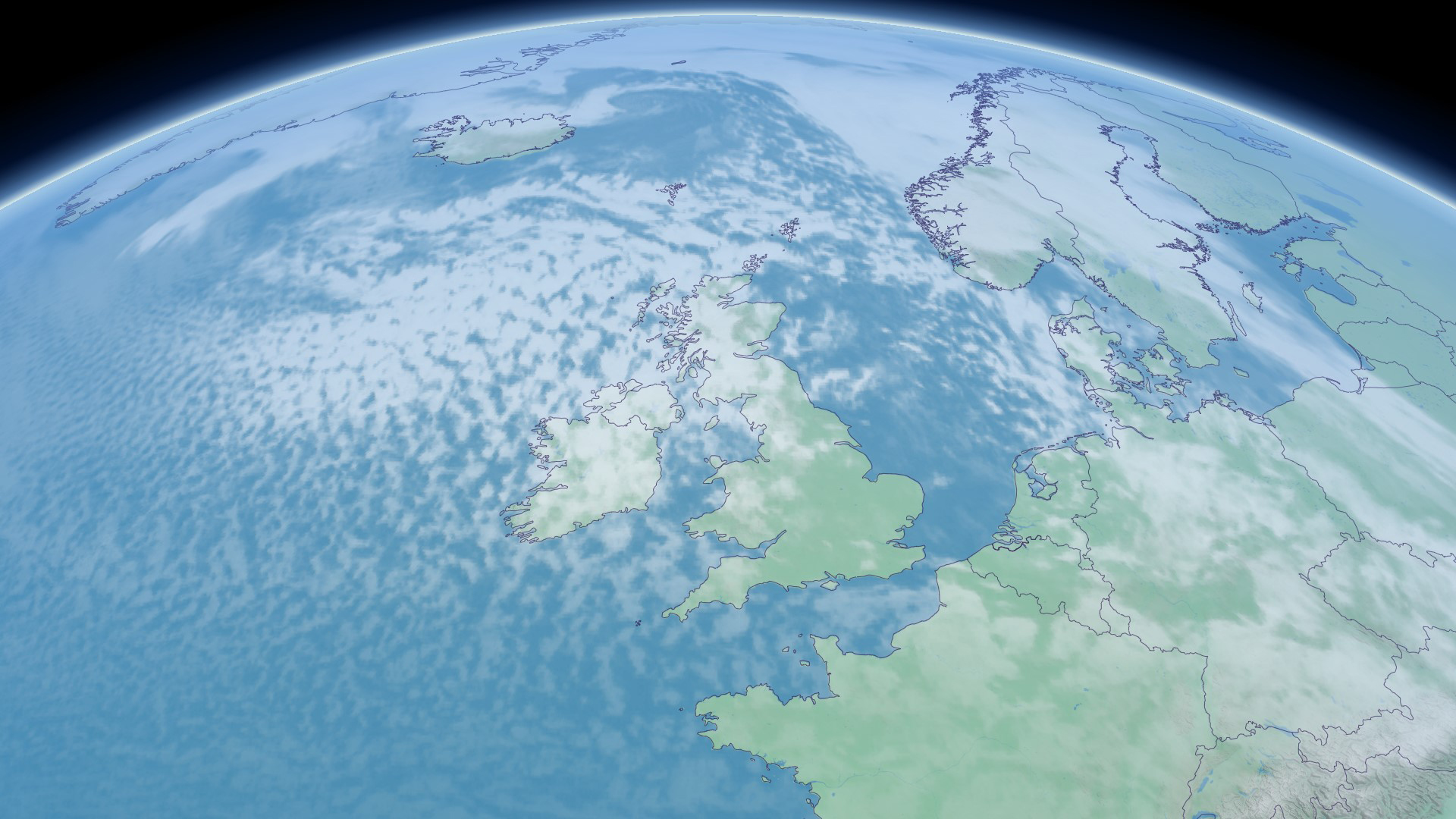

A look at the satellite image from Tuesday afternoon shows no discernible swirl of cloud that many of us would identify with a storm.

So what was it that was being named? Well, effectively some very strong gusty winds associated with heavy wintry showers that were rolling into the west coast of Ireland off the Atlantic Ocean.

Yes, gusts of 85mph were recorded at Mace Head and 74mph at Sherkin. However, these are very exposed coastal locations, and weren’t representative of what nearly all of the rest of Ireland experienced. Dublin Airport recorded gusts of just 35mph, Sligo Airport 48mph and Cork Airport 47mph.

A storm is when a cohesive, identifiable zone of damaging winds moves through a wide area; give or take 10-15mph differences to account for more exposed coasts and hills.

This is not what happened on Tuesday. Yes, for many places it was a very windy, gusty day, but it wasn’t a storm.

Met Eireann’s response to my criticism

In an interview with Newstalk Breakfast, reported in the Irish Times, Met Eireann forecaster and chairwoman of the European Task Team for Storm Naming, Evelyn Cusack, described Met Eireann’s process of naming storms and issuing warnings.

Ms Cusack explained that Storm Fionn was not a traditional swirling vortex storm and that Met Eireann had issued the storm warning because of the risk of high seas and dangerous conditions on Ireland’s west coast.

“There have been tragic deaths involving people swept off rocks and cliffs. Conditions can be very dangerous,” she said.

“I don’t think you can say we were being too cautious. The conditions we predicted did occur.”

Ms Cusack said that although Storm Fionn was not a traditional storm, it fulfilled Met Eireann’s criteria and she was certain that people on the streets had experienced storm force winds.

Storm naming: a joint initiative, different warning criteria

Whilst it is true that both the Met Office and Met Eireann name storms when there are amber or red wind warnings, the criteria used to issue these warnings are not the same.

The Met Office uses impact-based criteria, which is based on the level of expected impacts the weather will bring.

Met Eireann uses fixed numerical criteria, which means a storm will be named whenever mean wind speeds are between 65 and 80 km/h and/or gusts between 110 and 130 km/h.

So even though the storm naming system is meant to be a joint initiative, the criteria used by each meteorological service are different.

To provide an example, it would be like different states of the US using different thresholds to define a hurricane, rather than the universally agreed threshold of sustained winds above 73mph. It would just end up being confusing – not only for the public, but for the media trying to cover the storms.

The problem with using fixed numerical criteria

The Met Office moved away from using fixed numerical criteria for issuing warnings years ago, which was a good thing, in my opinion, as they are restrictive when it comes to dealing with the fickle nature of the weather.

For example, 60mph gusts of wind early in autumn are much more disruptive and likely to blow down trees than later in autumn when they are bare, as the leaves act as sails catching the wind.

Using an impact-based criteria allows forecasters to incorporate this factor into any warnings produced. Using fixed numerical criteria doesn’t, as the only thing considered is whether the wind strength reaches the fixed threshold or not.

For completeness, another example. Sometimes the UK and Ireland can have gales and stormy weather in June. This is obviously a time of year when more people are outdoors and carrying out leisure activities.

Using impact-based criteria allows forecasters to take into account the unseasonable timing of the bad weather and still issue a warning – even if the winds are not quite as strong as an autumn storm.

However, using fixed numerical criteria can limit the issuing of warnings in such circumstances, as a fixed threshold may not be reached.

In light of Tuesday’s case with Storm Fionn, there was no storm, but the gusts of wind on the west coast of Ireland reached the fixed numerical criteria for an amber wind warning to be issued, which in turn meant that a so-called storm was named.

Storming naming: a useful tool when used sensibly

When the storm naming system started, I was initially skeptical of how it would work logistically, but over time, I have seen the benefits of using it – albeit sensibly and when the weather merits it.

It has been demonstrated to raise awareness, provide more of a connection for people to stormy weather and is useful for referencing in the media – especially on social media platforms.

However, it needs to be remembered that it was always intended to be used as a valuable tool for when the weather is especially severe, not just more typical rough autumn and winter weather.

And, in my opinion, that is what happened on Tuesday with the naming of Storm Fionn – for what was a pretty typical bleak, windy January day on an Atlantic-facing coast.

I’ve criticised, I hear you shout, so inevitably, I should offer some ideas as to how the system could be improved for future use. So here is what I would like to see the Met Office and Met Eireann sit around the table to discuss;

· Both the Met Office and Met Eireann using exactly the same criteria to name storms – be it numerical or impact-based (preferably the latter)

· Work closer together to adequately establish whether or not a storm should be named for the UK and Ireland

· Consider whether the issuing of an amber wind warning should automatically mean that a storm is named

· Reserve the use of storm naming for widely-damaging, dangerous, high-impact events and not what could be considered typical, locally rough autumn and winter weather.

In the meantime, let me know what you think about naming storms in the comments below, or on Twitter – @liamdutton