Can UK schools reboot ‘joke’ computer lessons?

A “chronic lack of specialist teachers” is causing school pupils to reject computer studies, says the Royal Society. Channel 4 News examines how British teenagers can be switched back on.

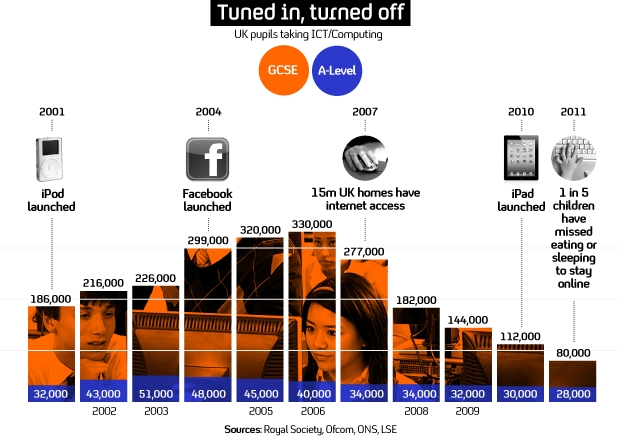

The number of British teenagers choosing to study computing has nosedived during the internet boom of the last decade, with fewer pupils taking GCSEs and A-levels in ICT (Information and Communications Technology) today than before the arrival of the iPhone, BlackBerry and social networking.

The solution is to scrap the label “ICT”, instead teach “digital literacy” as a skill not a subject and to recruit more specialist teachers, according to a report by the Royal Society.

The study, Shut down or restart?, reveals that only 35 per cent of ICT teachers are specialists, compared to 74 per cent in maths and 80 per cent in English.

Its chief author, Professor Steve Furber, who helped design the now legendary BBC Micro computer (pictured below), has called for action “not only on the curriculum itself but also to recruit and train many more inspiring teachers to reinvigorate pupils’ enthusiasm for computing”.

More from Channel 4 News: 'Boring' ICT lessons to be wiped

The focus of the drive is to create a nation of people who can “create technology, not just use it”.

“It’s also about democracy. Young people are increasingly technologically aware,” Prof Furber told Channel 4 News.

“But if they don’t understand the nature of the algorithms between software, then they can’t behave as democrats, they can’t behave as informed citizens and they can’t behave as informed consumers – and they become technologically disenfranchised.”

ICT has been a joke for a while. Naomi Alderman

The report also criticised over-cautious internet security in schools. Prof Furber said conservative security policies had become an “impediment” to learning.

The analysis by the Royal Society revealed a 57 per cent decline in teenagers taking computer-related GCSEs over the last decade. At A-level there was a 60 per cent slump. The trend continued in university applications with colleges said to be “lukewarm” about incoming students with an ICT A-level.

All this while Facebook, the college project of a young Mark Zuckerberg, swept across the globe via a riptide of increased broadband speeds, hashtags and touch screens.

“ICT has been a joke for a while,” reckons Naomi Alderman, a writer and online games developer.

She told Channel 4 News: “No child takes more than a few days to learn how to use any software – while learning to code is a very valuable skill.”

“There’s absolutely no reason why a bright, able secondary school pupil shouldn’t be able to develop an app and bring it to market. In fact, they might make enough that way to mitigate the horrendous university tuition fees.”

Josie Fraser, ICT strategy lead at Leicester City Council, has welcomed the report but she told Channel 4 News some of its recommendations are “limited”.

“The report currently defines digital literacy in a very limited way. If we are going to ensure that young people and children are in a position to take advantage of, and make a positive contribution to, a society that has been transformed by its use of technology, then we need to be more ambitious about what we mean by digital literacy.

“The report is a good starting point for this, but digital literacy is not just the ability to use tools, platforms and devices, it’s also the ability to critically evaluate how and why we use these tools, and the ability to use them as active social citizens.

“I would like to see a more ambitious definition of and aim for digital literacy.”

‘Start making things’

Fraser highlights an American project, Code Academy, which helps young people get to grips with the starting blocks of computer coding.

“They launched a project on 1 January called Code Year – encouraging everyone to make 2012 the year they begin to learn to code,” she explained.

“Participants are emailed weekly programming lessons and exercises. Within two days of launch the project had received an incredible 100,000 sign-ups.

Regardless of how many people keep their new year resolution – the uptake clearly shows how much current interest in programming there is. I don’t know how many UK schools, teachers and students are currently following the lessons but it’s the kind of initiative I am keen to promote.

“Fledgling UK-based initiative Coding for Kids is a great example of the current appetite to introduce children and young people to the fun and benefits of coding.”

Meanwhile, Naomi Alderman’s advice to school pupils is to “start making things, even small things”.

“Make stuff that works, that you think people will like, then put it online and see if people want to buy it,” she said.

“Try finding via a crowdfunding site like IndieGoGo or Kickstarter – the response you get will tell you if your idea is a ‘big’ idea that people are interested in or a smaller one which isn’t worth wasting your time on.

“The barriers to entry are so low now that all you need is a great idea and the ability to create it and you can find your way to market.”

The Royal Society report, which has the backing of industry heavyweights including Google and Microsoft, picked out Israel, Germany and South Korea as nations the UK could learn from. All have revamped their computing curriculums in the last 20 years in response to a fast-changing technological world.

We need a new generation of teachers to take up the challenge of enthusing future generations. Professor Steve Furber

As has been successful in these countries, the study recommends the separation of computer science (as Furber puts it “what’s in the box”) from information technology (the study of systems and their use in industry and society).

Matthew Harrison, director of education at the Royal Academy of Engineering, told Channel 4 News: “We should be giving students a coherent, balanced curriculum, to give them the widest options for progression.”

Prof Furber concluded: “Thirty years ago I helped design the BBC Micro, the first computer created to educate and inspire children of the potential of computer science.

“Yet today, when computers have become integral to every part of our lives, we see young people turned off by computing in schools.

“We need a new generation of teachers to take up the challenge of enthusing future generations.”

The BBC Micro computer which launched in 1981 became a regular feature of UK classrooms. One if its designers was Prof Steve Furber.