Coronavirus claims first British life

A severe respiratory illness linked to the common cold has claimed its first life in Britain, writes Science Reporter Asha Tanna.

A man died at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham after contracting the novel coronavirus.

The 39-year-old victim had a weakened immune system, which is believed to have left him vulnerable to the infection. He was one of three people in the same family with the virus.

Respiratory experts have stressed the risk to the general public “remains very low” but scientists remain on high alert as viruses can mutate.

It is thought the victim caught the virus from his father who had recently visited the Middle East and Pakistan. The father is still being treated at a hospital in Manchester. The family members make up three of the four confirmed cases in Britain. A 49-year-old Qatari man was treated at a London hospital in September for the virus.

Middle East

The coronavirus was first identified last year in the Middle East and most of those infected had travelled to Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Jordan or Pakistan. There have been 12 confirmed cases reported worldwide – four of those in the UK. But despite the relatively low number of cases, it has killed half of those who have contracted it.

Professor John Watson, from the Health Protection Agency, said: “If novel coronavirus were more infectious, we would have expected to have seen a larger number of cases than we have seen since the first case was reported three months ago.”

“Only if the virus adapts to the human body does the potential for more widespread infection arise. There is no evidence for this type of spread so far.” Professor Ian Jones

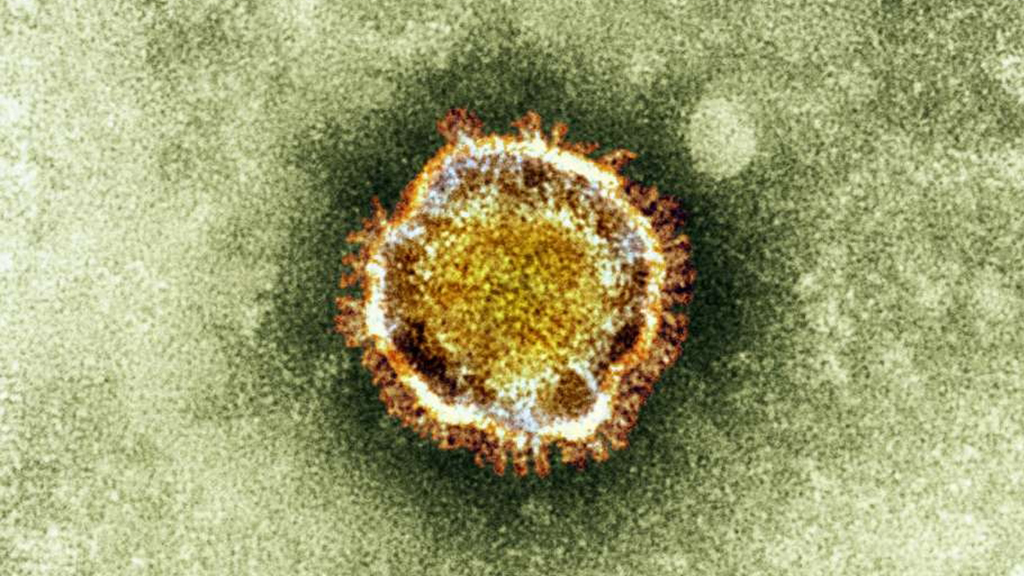

Coronaviruses cause most common colds but can also cause SARS – severe acute respiratory syndrome. The SARS epidemic caused a major international health scare after it killed more than 800 people in China in 2003.

Severe

But the new strain of coronavirus is particularly severe, as it can cause kidney problems, breathing difficulties and fever. The origin of the virus is still unknown, but one theory is that is may have come from animals and appears to be closely related to a virus in bats.

Ian Jones, professor of virology at Reading University, said there is no need to worry at this stage. “The pattern so far is of an occasional zoonotic occurrence, not an outbreak. You have to remember that these patients were flown in to the UK for treatment; the virus was not encountered here. The father to son transmission does not signify transmission on a wider scale”, he said.

He added: “The most likely outcome for the current infections is a dead end – that is, the virus will become extinct locally. This is by far the most usual outcome for such zoonotic infections, infections that are normally restricted to animals but occasionally infect people.

“Only if the virus adapts to the human body does the potential for more widespread infection arise. There is no evidence for this type of spread so far.”