David Bowie: Starman for a new generation

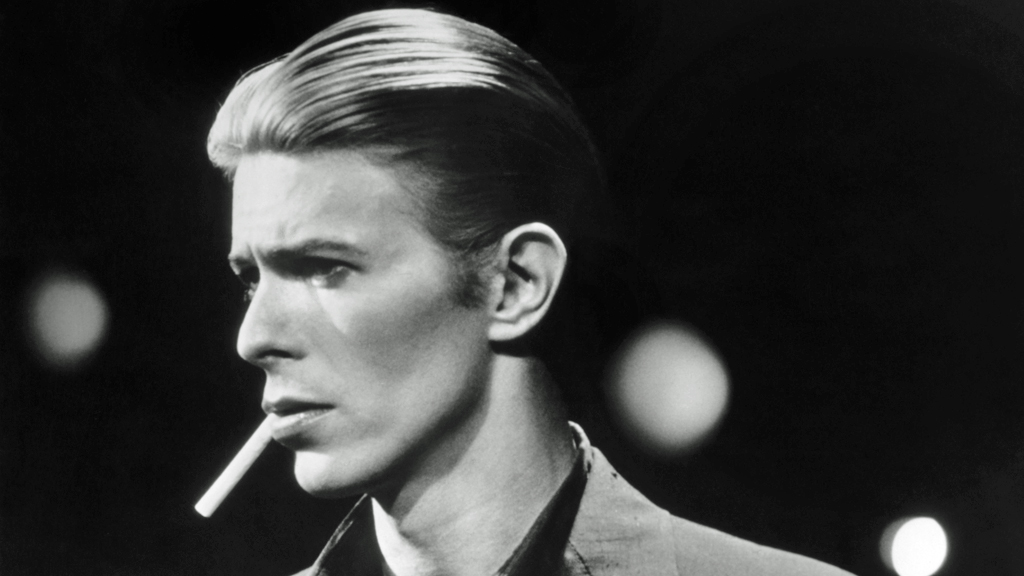

Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, the Thin White Duke were all fabulous, exotic personas from the 1970s. But as a new exhibition opens in London, what does David Bowie mean for young people today?

In the foyer, a film rolls proclaiming “living is one big sculpture”, writes Fred Mikardo-Greaves. It is the central idea of David Bowie Is, the ambitious blockbuster show that has been three years in the making by the Victoria & Albert Museum.

Viewed through 21st century eyes, it is easy to dismiss David Bowie’s innovations. But the exhibition’s vibrant displays and forceful ideas manage to revitalise his work for the modern age.

The “one big sculpture” phrase applies easily to the man when he was at the height of his shape-shifting powers. But we also see a pre-Ziggy, pre-Aladdin Bowie, someone wrestling to find the most appropriate expression for his talents.

The exhibition’s vibrant displays manage to revitalise David Bowie for a modern age.

Back-lit by early idols like Little Richard, the Bowie of the 60s is one of small revolutions. “Davy Jones” cycles through a few looks, by turns coffee-house Bohemian, post-Jagger bluesman and experimental mime artist – several different people rather than a series of personas orbiting the moon of Bowie-ness.

It is with Ziggy Stardust that the V&A provides the first superb marriage of presentation and content. Warped by angled mirrors, the 1972 Top of the Pops “Starman” performance, thrilling even now, throws the viewer back 40 years. Propped in front is the snakelike “Droog” suit from the same clip.

Turning on his past

I missed the space race, Warhol, the cold war. I was born almost a decade after 1983’s Let’s Dance – generally considered to be Bowie’s last great LP. The Next Day, released earlier this year, was my first experience of him as an active figure in contemporary culture. Now, with David Bowie Is, a new generation can continue to revel in his uniqueness.

The V&A show demonstrates how Bowie fearlessly turns on his own artistic past. Prototype artworks for The Next Day, in the vein of the defaced Heroes sleeve, are shown beneath the vast canvas for the Scary Monsters and Super Creeps album, itself built from whitewashed Bowie stills.

Bowie’s world was the same as ours, but he made us see it through the stardust of Hunky Dory and Ziggy.

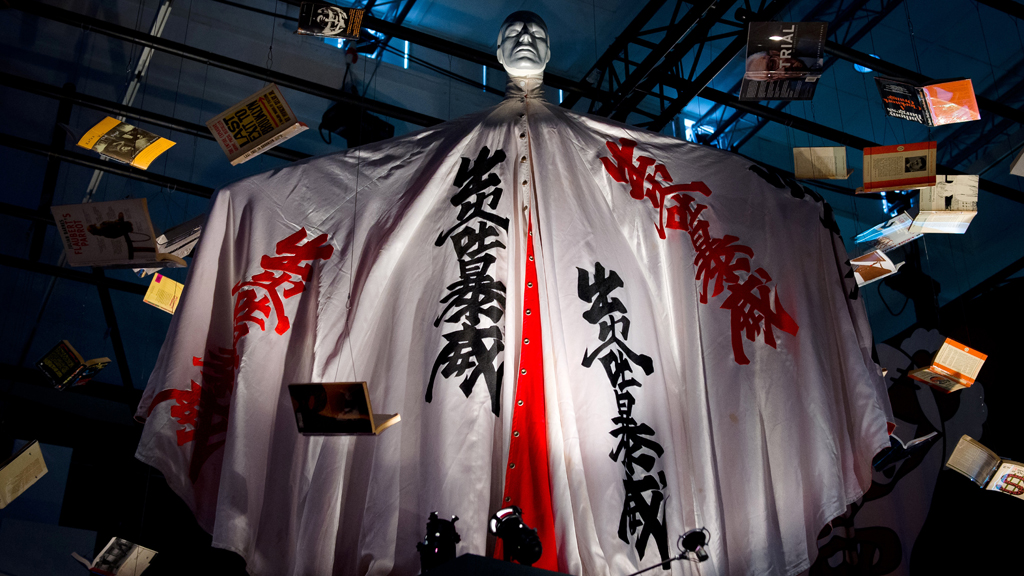

Elsewhere, the fabulous white Kansai Yamomoto costume (see below) stands, raised amid a shower of books and portraits of Bowie’s respected contemporaries – William Burroughs, Bob Dylan and so on. The severe lines of his Thin White Duke appear alongside a draft of lyrics for Station to Station. His 1983 Screaming Lord Byron costume, a billowing Paisley dream, expresses the spirits of Wilde and Hendrix.

Bowie’s most original secret was that his world was the same as ours, but he made us see it through the stardust of Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust. With David Bowie Is, he casts that stardust on a new generation.

David Bowie Is runs at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, from 23 March to 11 August