Does Ofqual’s report prove Michael Gove right?

Ofqual’s final report did little to clear up the GCSE English marking fiasco but in highlighting how some teachers “generously” marked GCSE work, does it vindicate Michael Gove’s proposed reforms?

Despite efforts to blame the system, rather than the teachers, for what it called “generously marked” GCSE coursework, the headlines to emerge from Ofqual‘s final report into the GCSE marking controversy managed to enrage the teaching profession.

The report was intended to shed some light on who should take responsibility for why thousands of GCSE pupils who took English in June missed out on their crucial grade C, because of a change in grade boundaries.

Instead it has delved deep into the murky world of assessment, and found that teachers are “over-marking” GCSE work, blaming pressure to achieve and an over-reliance on internal assessment within GCSE exams.

Problems cited by Ofqual:

> Complexity of qualifications

> Large proportion of teacher-marked controlled assessment made GCSEs “susceptible to pressures” such as performance tables

> Modular system of GCSEs, meaning that students already had a written exam grade before taking coursework

> Moderation by exam boards is not strong enough to identify wide-spread marking problems

The suggestion has struck a chord.

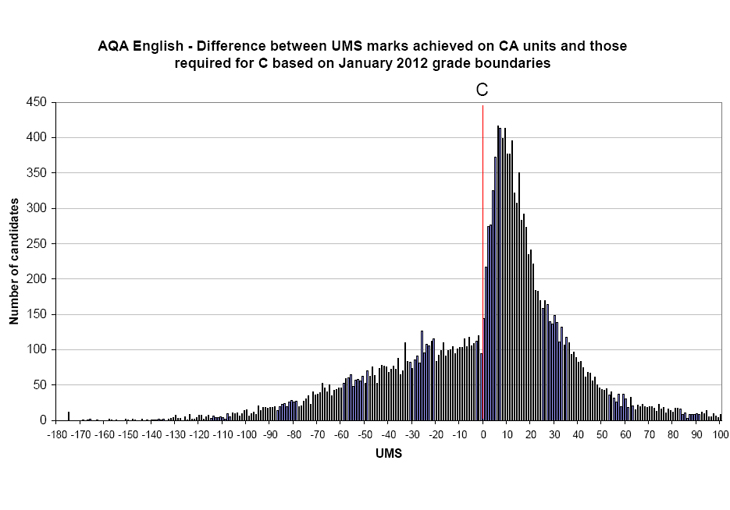

The report cites statistical analysis [see below] showing a sharp rise in the number of pupils who manage to get a C grade and implies that teachers over-mark. Ofqual was keen to say that many factors had an impact on this spike, including the modular system of English GCSEs; pressure on schools to achieve good English results; and monitoring by exam boards.

If judged purely on the ease of assessment, the statistics in the report could be seen to back up Michael Gove‘s favouring of longer written exams, rather than coursework or controlled assessment, which are marked by teachers.

And in highlighting the fact that many pupils have already sat so much of their exam that teachers know what grade they need to pass, the report also support the secretary of state’s proposal to scrap the modular element of GCSEs.

Independent investigation?

However those within the education world have raised the question of whether any regulator can fairly investigate its own role in a controversy that it was supposed to be monitoring. One source told Channel 4 News that the report appears to play into Michael Gove’s preferences, and indeed some believe that the change in exam boundaries was in response to complaints from the government about exams getting ever easier.

It doesn’t seem to be that they’re actually trying to establish who deserved the grade or not. That doesn’t seem to be the debate any more – it’s all about process. Secondary teacher

Headteachers have called for an independent inquiry into this year’s English results, and an alliance of 150 schools have lodged a judicial review into AQA and OCR exam boards with the High Court.

They claim that around 10,000 students missed out on a grade C as a result of two things: the exam boards’ decision to raise the grade boundary between January and June, and Ofqual’s decision not to change the June grades, instead allowing pupils affected to take a resit.

The D/C ‘academic cliff-edge’

Regardless of the political implications, the report also highlights what teachers have been saying for years: that there is far too much emphasis put on helping borderline pupils achieve a grade C, at the detriment to other pupils. And that teachers are under pressure to help boost grades where they can.

Ofqual quotes a teacher writing anonymously on an online teacher forum: “When I’ve dared to suggest that the CAs (controlled assessments) should be done in exam conditions and that lots of schools are doing that, I’m told that that is rubbish, that CAs are really coursework, and that we have to cheat because other schools will be doing so, and we cannot afford to let our results slip at all.”

Chris Husbands, Institute of Education director, told Channel 4 News that the pressure to do well has created an unbalanced system.

“If you want to be to get attention in the education system, you need to be a white working class boy on a D/C academic cliff-edge,” he said.

But he said the report failed to address how to develop a better system of assessment and accountability.

“We should have an accountability system that promotes the learning of all children. But ultimately this report is very disappointing. It fails to question what this means for the long-term development of the assessment system.”

And while it provides a comprehensive analysis of the current assessment process in schools, what the report fails to do is clarify the central issue of this year’s GCSE English exams.

“It doesn’t seem to be that they’re actually trying to establish who deserved the grade or not,” one secondary teacher told Channel 4 News.

“That doesn’t seem to be the debate any more – it’s all about process.”