Does the Turner Prize back art world winners?

It may attract the most attention of all the art prizes around. But aside from the unmade beds and piles of poo, does the Turner Prize signal success for the winner? Channel 4 News investigates.

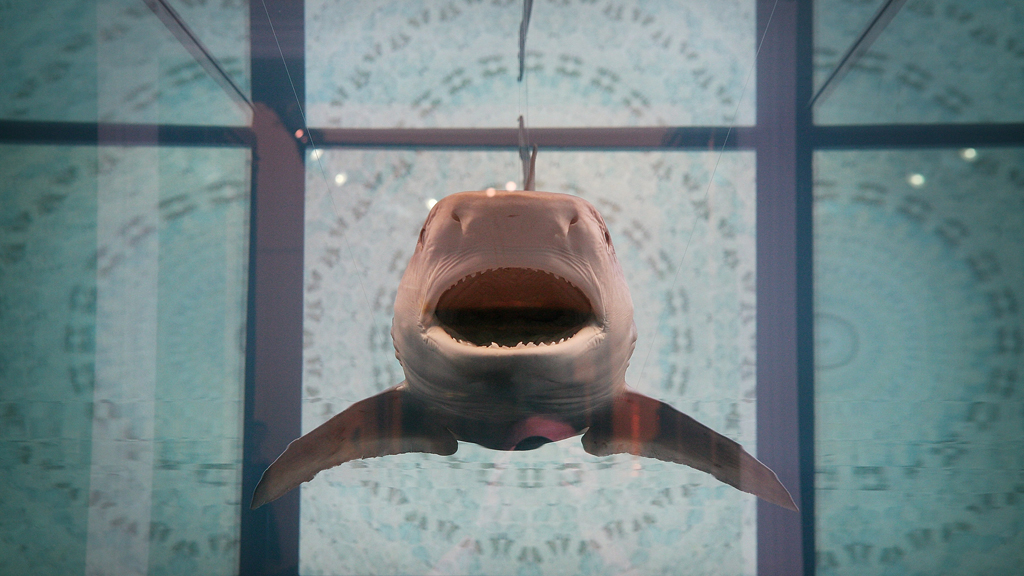

The artist Douglas Gordon last week discovered that one of his sculptures, with an insurance value of around £500,000, was stolen from a Christie’s auction house. Melted down, as the artist suspects has been its fate, it is estimated to be worth £250,000 – half the value, and nowhere near the $12m paid for Damien Hirst’s dead shark.

But would either of these artists have such value attached to their work if they had not won the Turner Prize? The award certainly guarantees immediate fame and media attention, often by courting controversy. However, many of the Turner Prize-winning works were not designed to be bought and sold in the art market, and in terms of the monetary value of the artist’s work, the answer is more complicated.

When researching his recent book, The $12 Million Stuffed Shark, economist Don Thompson says the consensus among dealers was that a Turner Prize nomination would guarantee good representation – but not necessarily increase prices. Pots made by former Turner Prize winner Grayson Perry for example, can be worth up to £50,000, and his 2011 exhibition at the British Museum was sponsored by the luxury brand Louis Vuitton.

But while winning in 2003 certainly gave the transvestite potter a platform, it was also the way he used his elevated profile – through documentaries or media interviews – that helped translate winning into commercial success.

Commercial gains

Of this year’s shortlist, favourite to win is Paul Noble, whose black and white sculptures of piles of copulating poo and detailed pencil drawings, have been critically acclaimed. The highest price ever paid for his work is £60,000 (or $120,000), but on average it attracts around £40,000 to £50,000 at auction, according to Artnet.

But winning the coveted prize is “only one element of the financial package of the artist”, Ben Hanly, contemporary art specialist at Artnet, told Channel 4 News. “What is important after that is how commercial their work is, and how strongly that is driven by the galleries that represent them.”

Another factor that influences value is consistency: ideally an artist needs a wide base of collectors to boost the price up and contribute to an overall trend, rather than a one-off spike. Arguably the Turner Prize is a route to this, launching the artist into the public consciousness.

Read Culture Editor Matthew Cain: What, no sniping at the Turner Prize shortlist?

Breaking the mould

The mischevious art prize is best known for breaking the mould and awarding art that is more conceptual, often with a novelty or shock factor: Tracey Emin‘s unmade bed, those lights turning on and off, or Gillian Wearing’s film, 60 minutes of silence.

But generally the more conceptual an artist is, the harder their work is to market commercially, says Ben Hanly. A gallery does not have a ready-made procedure for buying and selling performance art or mass sculptures, for example, so it is more difficult and unpredictable to exhibit – or own, for that matter.

That could cause a problem if this year’s nominees are after the big bucks. For the first time, a performance artist has made the shortlist while two video installations have also made the grade – one lasting 93 minutes.

But success in art is not just determined by monetary value, of course. While the Turner Prize may not guarantee commercial benefits straight away, it is still respected for reflecting excellence and picking those who are at the top of their profession within the realms of its particular brand of art.

“Whomever is nominated or wins, one of the Turner Prize’s objectives is to draw public interest and discussion to British contemporary art,” Mr Thompson told Channel 4 News. “It has been wildly successful in doing that.”

Thankfully, in art at least, it is not always all about the money.