Egypt’s poll a popularity contest for Sisi’s military

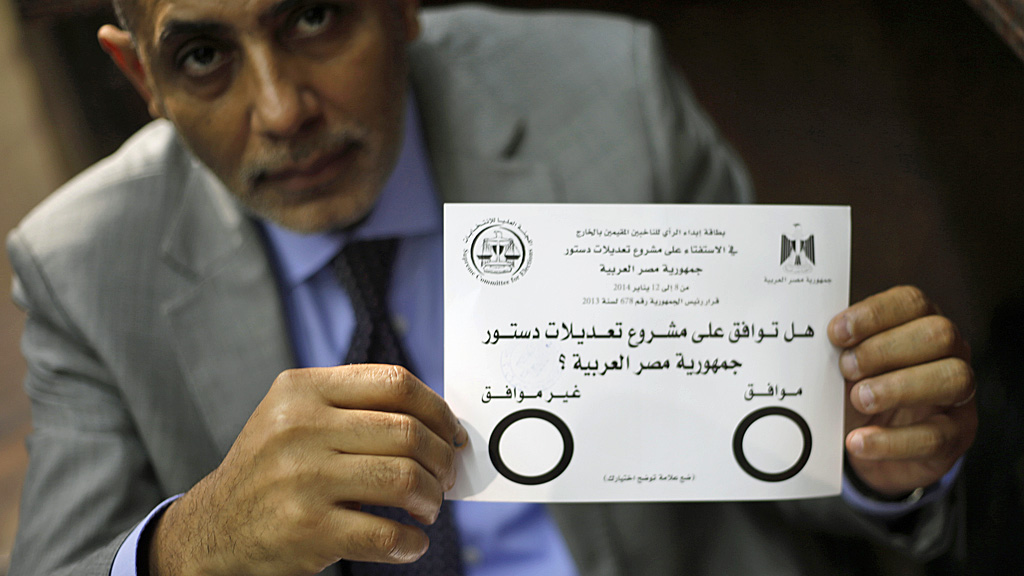

Today Egyptians vote again on a new constitution – a draft document that would leave the army’s powers intact and cast the Muslim Brotherhood back into the political wilderness.

Today Egyptians are being asked to vote on a new draft constitution that paves the way for fresh elections and limits the next president to two terms in office – contrasting with the five six-year terms accorded to the former president Hosni Mubarak, writes Jane Kinninmont.

But the draft document would also impede civilian oversight of the powerful armed forces, enshrining the secrecy of the military budget, and stipulates that the defence minister needs to be a military officer. It continues the general trend seen since the overthrow of Mubarak: laws, leaders and some institutions are being changed, but the structural powers of the army remain largely intact.

In this context, today’s referendum will be seen by many as a popularity test for the country’s military, six months after the overthrow of Mohammed Morsi, the former elected president. The previous constitution was suspended by the army when it announced Morsi’s departure in July 2013. Suspending the constitution is a key characteristic of a military coup, by most definitions. Likewise, agreeing a new one is a crucial element of Egypt’s political transition.

Polarised campaign

The constitution touches on an array of issues beyond the role of the military, including the role of parliament, Islam, human rights, gender, the role of women and trade unions.

There will be some “yes” voters who have little love for the military, and may not agree with everything in the draft, but think having a constitution in place will speed up the process of presidential and parliamentary elections, and help put the transition back on track. Currently the country has an interim president, and no parliament. (The draft stipulates that both sets of elections should be held within six months of the constitution being ratified.)

The military-backed government see voting as a statement about political allegiance and the legitimacy of the transition process.

But in general, the campaign has become polarised between supporters and critics of the military-backed government, who see voting as a statement about political allegiance and the legitimacy of the current transition process. The biggest opposition force is the Muslim Brotherhood, the movement that Morsi came from, which is boycotting what it calls a fake vote.

One of the key youth movements behind the 2011 uprising, April 6th, is also boycotting the poll. Some of its leaders, such as Ahmed Maher, have recently been arrested for violating tough new anti-protest laws. Meanwhile, the authorities have harassed and arrested people who campaigned for a “no” vote, and flooded the state media with “yes” campaigners.

Constitutional privilege

Agreeing a new constitution has been fraught with tensions since 2011, since both the actual content of the constitution, and the political process itself, are being disputed. Egyptians voted on their last new constitution as recently as December 2012.

That constitution was prepared by a 100-strong committee appointed by Morsi’s government; some of the liberal and leftist members walked out, saying the process was biased against them and that it overemphasised the Brotherhood’s interpretation of the role religion should play in politics and society.

A yes vote may be seen by the military as helping to pave the way for the head of the army, General Sisi, to stand for president later this year.

For instance, it said the state should safeguard “public morality” and the “character of the family”, prohibited “insults” to Islamic prophets, and gave senior clerics from the Islamic university al-Azhar the right to be consulted in matters pertaining to Islamic law.

The new draft has removed these provisions, and also includes more language on gender equality. While these identity issues have dominated the debate, the two constitutions both left the military with a privileged position in the Egyptian political system, including the provision that civilians can be subject to military trials for a range of crimes.

Another low turnout?

In the 2012 case, the Brotherhood’s critics were divided over whether to vote against the draft or boycott the referendum altogether. Had they voted, they might have defeated the draft. Instead, it was approved by 64 per cent of those who voted – but less than a third of eligible voters actually turned up at the polls, and there were reports of dodgy election practices.

This outcome allowed both sides of the debate to think they had won: the government said its constitution had been legitimised by a majority vote, while the opposition saw the minority turnout as evidence that the constitution was illegitimate.

This time, the draft constitution has been prepared by a committee of 50 appointed by the military-backed government, including just two Islamists and no Muslim Brotherhood representatives. Again, it is likely there will be a high proportion voting yes, but a low overall turnout; again, the legitimacy of the vote will be disputed, and both sides will claim victory.

A yes vote – especially if the turnout is higher than in the 2012 referendum – may be seen by the military as helping to pave the way for the head of the army, General Sisi, to stand for president later this year.

Meanwhile, the Muslim Brotherhood, which was declared a “terrorist organisation” in December, is hunkering down for a renewed period in opposition – a status that is more familiar to it than government.

Jane Kinninmont is Senior Research Fellow and Deputy Head, Middle East and North Africa Programme, at Chatham House. Follow Jane on Twitter: @janekinninmont