One in nine women in England takes antidepressants, according to the latest official national health survey.

Just over 11 per cent of women and nearly six per cent of men over 16 said they had popped at least one pill prescribed for depression within the last week.

Other statistics show that doctors wrote more than a million prescriptions for antidepressants a week last year, almost double the amount ten years ago.

Is England drowning in an epidemic of depression, or are doctors too quick to hand out the tablets?

The analysis

The latest evidence we have for the widespread use of antidepressants comes from the Health Survey for England 2013, published today by the Health & Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC).

Amongst all men and women, use of antidepressants was about 5.5 per cent and 11 per cent. That means more women were taking medicine for depression than prescription painkillers or antibiotics.

The figures are also broken down by age and income. Among the lowest earning fifth of patients, more than 10 per cent of men and as many as 17 per cent of women were taking pills prescribed for depression.

This is the first time prescriptions have been included in the survey, so we don’t know that there has been a rise in antidepressant use, but we can make an educated guess.

Other HSCIC data shows that the number of prescriptions almost doubled between 2003 and 2013, rising from 27.7million to 53.3million.

This includes all kinds of antidepressants, but the drugs most commonly prescribed now are Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) – pills like Prozac which are believed to increase levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin.

Why are we increasingly relying on these drugs? There are a number of theories…

We’re more depressed

One suggestion is that the pressures of modern life – perhaps exacerbated by post-crash financial pressure – are getting too much for us.

That was a possibility floated by researchers at the Nuffield Trust, who found that prescriptions rose by 6.7 per cent a year from 1998 to 2008, but went up 8.5 per cent a year between 2008 to 2012.

Could the financial crisis have led to an acceleration in prescriptions of antidepressants? Possibly, but the same research found that prescribing had been on the rise since at least 1998, long before the crash. And it has continued to rise as the economy recovers and unemployment falls.

Actually, we can’t even be sure that antidepressants are really being used to treat depression.

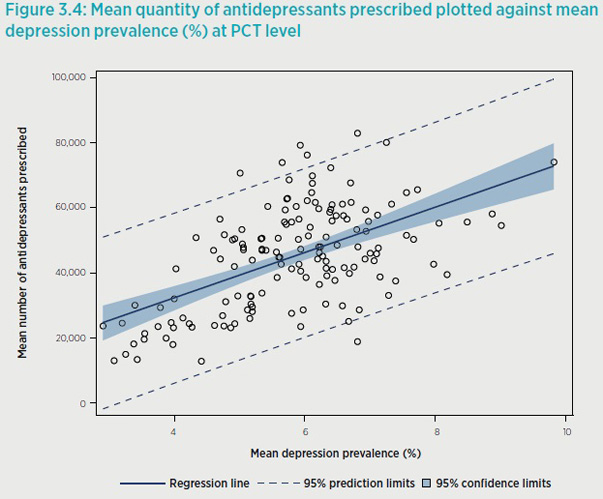

The Nuffield Trust study found that there was a pretty weak correlation between the prevalence of depression in an area and the amount of drugs being prescribed by local GPs.

And it noted that cases of diagnosed depression went up by just over 7 per cent a year between 2009/10 and 2011/12 – while antidepressant prescriptions rose by more than 17 per cent.

The pills work

Perhaps there’s a simple explanation. If antidepressants work, we would expect more of them to be dished out.

But as we have seen, it’s not clear that everyone given the tablets is actually suffering from clinical depression.

And then there is a big debate about how useful antidepressants really are for people diagnosed with depression.

Initial studies showed very positive results for SSRIs, but the research suffered markedly from the kind of publication bias that has recently been highlighted by the campaigning doctor and writer Ben Goldacre.

Studies that showed negative results mysteriously failed to get published, fatally skewing the information presented to doctors.

When researchers looked for trials that had been published on the effectiveness of 12 antidepressants, they found 37 which reported positive results and only one that was negative – a clear win for the drug companies.

But 22 trials with negative results had not been published and 11 more had been written up in such a way as to make bad results sound better. At first glance, it looked like 94 per cent of the drug trials had been positive, but the real figure was just 51 per cent.

In 2008 Professor Irving Kirsch tried to get around this problem by using the US Freedom of Information act to to get the data on all clinical trials submitted to the Food and Drug Administration for the licensing of four new antidepressants.

His meta-analysis found that people given anti-depressants did indeed get better. But so did people given placebo (dummy) pills, and the difference for most patients was so small as to be clinically insignificant.

This was hugely controversial stuff, but subsequent studies have produced similar conclusions. This more recent meta-analysis concluded: “True drug effects were nonexistent to negligible among depressed patients with mild, moderate, and even severe baseline symptoms, whereas they were large for patients with very severe symptoms.”

Current advice from the Royal College of Psychiatrists is more upbeat.

It says that 50 to 65 per cent of people with depression will feel much better after three months of treatment compared to 25-30 per cent given a placebo. The college says medication is not suitable for people with “mild” depression.

Doctors are over-prescribing

This is a claim made by some prominent British and US academics and psychiatrists who are sceptical about the benefits of antidepressants.

Dr James Davies, author of a book on the subject called Cracked, told FactCheck: “The so-called advantages of these medicines have been oversold and overplayed by the pharmaceutical industry and by members of the medical profession who have been recruited by the industry to sell up the advantages to other doctors and to their patients.

“This has led to a belief that people in the general public tend to have that these pills tend to work. They don’t work better than placebo for most people.”

Dr Davies doesn’t buy the theory that recent economic events have led to an epidemic of depression.

“I think what we have seen is a cultural shift in how we manage and respond to emotional discontent. There is a growing suspicion of emotional discontent and a growing need to get rid of it as soon as possible. Pills seem to offer us a solution.

“Most people taking antidepressants are not mentally ill. They are suffering from natural, normal – albeit painful – human responses to the different things they have got themselves caught up in – things that these medicines were never designed to treat.

“People are presenting to their GPs with common life problems and the GPs don’t want to send them away empty-handed.”

While GPs are “wonderful people who do great work”, he said, “serious questions need to be raised” about whether family doctors are the best people to decide whether patients will benefit from antidepressants.

Of course this is only one view, and the accusation of over-prescription is strenuously denied by many doctors and the organisations that represent them.

The Royal College of General Practitioners chair Maureen Baker said today: “Medications are an extremely effective way of treating illness, either as a one-off or on a long-term basis, as long as they are appropriately prescribed and carefully monitored.

“Prescribing is a core skill for GPs and patients can be assured that their family doctor will prescribe medication only when necessary and where other alternatives have been explored. GPs also have to adhere to strict and robust monitoring systems.”

She added that GPs “GPs strive to keep their prescribing skills up to date to provide the safest possible patient care” and have to demonstrate competence in prescribing and managing medicine as part of their training.