Some 16 per cent of people who died in hospital after testing positive for the coronavirus are from ethnic minorities, new NHS England data shows.

News reports have contrasted this figure with the fact that 13 per cent of the population of England identified themselves as being from an ethnic minority in the last census.

This has led some outlets to suggest BME patients are more likely to die from coronavirus than white people.

But the data isn’t so clear.

The figures

The NHS stats look at people who died in hospital after testing positive for coronavirus up to 5pm on 17 April.

Of those, 74 per cent were recorded as white, 7 per cent as Asian, and 6 per cent as black. An additional 1 per cent were listed as having a mixed background.

Is this about ethnicity or geography?

It’s tempting to compare this data to the national figures on ethnicity – just as several media outlets have done.

But that doesn’t actually tell us much. We know that cities – especially London and parts of the West Midlands – have been hit first and hardest by the crisis so far. And we know that a greater proportion of people in these areas come from ethnic minorities than the England-wide average.

If we want to find out whether BME coronavirus patients are more likely to die than white patients, we need to know more about the demographics of the places those patients lived.

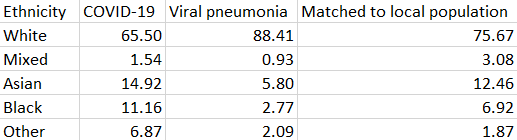

That’s what researchers at the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) have been doing with data on people in critical care. They compare the ethnicity of ICU coronavirus patients with the local authority wards in which those patients live.

As FactCheck found earlier this month, the ICNARC data has been widely misinterpreted as showing that BME patients are three times more likely to end up in intensive care with coronavirus. This misunderstanding has been created by comparing ethnicity on ICU wards with the demographics of the UK as a whole.

Analysis in the latest ICNARC publication suggests that when compared to their local areas, white people are somewhat under-represented in critical care, Asian patients are very slightly over-represented, and black people are significantly over-represented. Though in the case of black patients, the most recent data suggests that the disparity is getting smaller as the epidemic progresses.

Unfortunately, NHS England doesn’t publish data to allow us to directly compare patient ethnicity and local demographics when it comes to deaths.

But we do know that the two places with the highest coronavirus death toll – London and the West Midlands, which together account for 47 per cent of hospital deaths – are also the most ethnically diverse regions of England.

So it is not necessarily surprising to see proportionately slightly more BME patients in the death toll compared to the England average.

The comparison relies on a small difference

The claim that BME patients are over-represented in the death stats rests on a small margin: 16 per cent of deaths versus 13 per cent of the wider population. So it’s very vulnerable to changes in the underlying data.

For example, it’s up to patients whether they record their ethnicity – and for 10 per cent of the deaths included in NHS figures, none was given. We simply don’t know whether the apparent over-representation of BME patients would still apply if we had ethnicity data on these individuals.

And more importantly, the data on England-wide ethnicity is from the 2011 census – so it’s nearly ten years old. We know that London and the West Midlands have both seen their BME populations increase since then. Some or all of the apparent ethnic disparity could be explained by the fact that there are more people from ethnic minorities in England today.

Hospital deaths are only part of the picture

And there are further limits to the NHS deaths stats. They only tell us about hospital patients: they do not include people who died in care homes or in the community.

This is significant when it comes to ethnicity because data from the last census in 2011 suggests that older people – i.e. the people most likely to live and die in care homes – are more likely to be white.

It may be that some of the over-representation of ethnic minority patients among hospital deaths is explained by the fact that white people – by virtue of being older on average – are more likely to die outside hospital and are therefore missing from this data.

Only once we combine the NHS stats with figures on deaths outside hospitals will we get a full picture of which ethnic groups, if any, are more likely to die with coronavirus.

The Office for National Statistics has been collating information on all deaths from Covid-19, but it’s not yet comparable with the latest NHS publication. The ONS told FactCheck today that they are in the early stages of a project that will allow figures on ethnicity and coronavirus to be linked to census data.

FactCheck verdict

New NHS data has led some to suggest that coronavirus patients from ethnic minorities are more likely to die than white patients.

That’s based on comparing the proportion of deaths from each ethnic group with the demographics of England as a whole.

But this is not a helpful comparison. It relies on data from the 2011 census – and we know that BME populations have grown since then.

And the two regions with the highest death tolls so far – London and the West Midlands – are also the most ethnically diverse parts of England. So we cannot say yet whether the death statistics are best explained by ethnicity or geography.

These new figures don’t tell us about people who died outside hospital. That’s significant because older people – i.e. those most likely to live and die in care homes – are more likely to be white.

We’ll only have a full picture of the ethnic breakdown of coronavirus deaths once we can reconcile hospital data with ONS figures on deaths in the community.

The NHS stats are also limited by the fact that in 10 per cent of cases, no ethnicity was given (this at the patient’s discretion).

Finally, we should remember that even if someone dies after testing positive for coronavirus, we don’t know whether it was the virus that caused the death.